Download PDF: Stephenson, Luther’s Wedding

ABSTRACT

Since 1994, the city of Wittenberg, in what was formerly the German Democratic Republic, has hosted an annual “Luther’s Wedding” festival. This carnivalesque city festival represents and actualizes the city’s imagination of itself, and its relation to a suppressed past. In an effort to deal with the economic, cultural, and social promises and problems of the reunification of Germany in 1989, the city turned to festivity to reinvigorate public life. The festival relies heavily on a human faculty central to the productive imagination-the mimetic faculty-and through this is having considerable success recovering and rebuilding a convivial culture. We see in the Luther’s Wedding festival that the productive imagination has the power to evoke and make present absent objects and new creations because it deals in both possibility and actuality. Imagination is more than visual; it is embodied, felt, and performed. Embodied imagination has transformative power; it can both make new and make a new social-cultural life.

Introduction

This photo essay and the accompanying film take as their subject the people, streets, and town squares of Wittenberg, Germany, home of Martin Luther. On four separate occasions between the fall of 2004 and the summer of 2006, I traveled to Wittenberg to conduct short, field-based studies of contemporary Luther-themed festivities and Protestant pilgrimages.1Through words, sounds, and images, I depict, describe, and interpret here a special occasion-Wittenberg’s annual Luther’s Wedding festival. My aims are two-fold: I want to evoke the sense of conviviality created by the festival, and I want to frame my presentation of convivial culture in a narrative about the decline and the return of mimetic practices.

In the following sections, I present a collage of images and text around the themes of conviviality and the “return of the repressed” to Lutherstadt Wittenberg, with “repressed” here referring to the conviviality, freedom, and spontaneity characteristic of carnival traditions. The accompanying film thickens the collage.2 As James Clifford writes, the “method of collage is not to blur, but rather to juxtapose distinct forms of evocation and analysis. The method of collage asserts a relationship among heterogeneous elements in a meaningful ensemble.”3

This “paper” is narrative rather than argument driven. My aim is to tell a story, or rather show or depict a story-a story about the loss and recovery of mimetic traditions in particular traditions associated with carnival. Among the “elements” presented here in ensemble form are Renaissance-era carnival, high unemployment in the former East Germany, systems of state surveillance, the paintings of Peter Breugel, play, the state of the contemporary public sphere, modernity, Spielleute, conviviality, imagination, and mimesis. As Clifford states, the method of collage “asserts” rather than argues. It aims to persuade, convince, and move.

Luther and Katie in Wittenberg’s Marktplatz. Photo by author.

Renewal

The people in Wittenberg’s streets at festival time are not cultural commoditizers but cultural animators. Below, the wedding couple, trailed by the wedding pole and wreath (a version of a maypole), process towards the Schlosskirche (Castle Church), with its imposing tower.

Wittenberg is located about an hour’s drive southwest of Berlin, in the former East Germany. The city’s claim to fame is that it was Martin Luther’s home for thirty-six years, and the seat of the German Reformation that included also figures such as Philip Melanchthon and Lucas Cranach. Wittenberg’s fame as a site of Lutheran heritage and tradition is occasioning festive celebration informed by the traditions of poplar culture that still existed at the time of Reformation, but were subsequently suppressed. Today, the small city of 50,000 is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and, since the German Wende4 of 1989, home to two annual, large-scale Reformation-themed festivals. Luther’s Wedding[5 is celebrated each June and again on Reformation Day at the end of October.

In the past one hundred and fifty years, Germany has witnessed more than its fair share of what Victor Turner termed social dramas. The nineteenth and early twentieth centuries witnessed the rise of the German Empire under Bismarck and the ascendancy of the Prussian state. The same era saw the Kulturkampf (culture war) against Catholics, as well as the secularization of society and battles between cultural Protestants and devout Pietists. The fighting of two world wars; the Holocaust; the division of the country into east and west; and the reunification, the Wende, of 1989: these events mark the tumultuous recent history of Germany. The Wende is a social drama that is still playing itself out, as the former East tries to find its footing in the new Germany and the new Europe.

In the post Wende era, residents of Wittenberg face numerous challenges. The area is plagued by high unemployment and the difficult transition to a twenty-first century global economy. The repressive legacy of communism has had a negative impact on the development of participatory democracy and an engaged public sphere. The former East Germany was a repressive state. People lived in a world where the Stasi (secret police) would entice or coerce family members to spy on one another. Speaking out against authority or the state was an act that could have serious repercussions. Citizens face difficult questions of history and memory in light of East Germany’s fascist and communist past, and the region, like other areas in Europe, has seen the rise of right wing political parties in recent years. There remains uncertainty and ambivalence about the place and role of the former “east,” in the new, reunified Germany. The town is in the process of receiving a face-lift, the gray, drab, industrial ethos of Chemischestadt Wittenberg (“chemical town Wittenberg,” as the town was dubbed by the state government in the late 1960s) is being replaced with color, community engagement, and even flare, but the process is long and difficult.

When East Germans poured across the border in November of 1989, they had two primary destinations: the homes of friends and family, and shopping centers. The peaceful revolution was also a consumer revolution, born in part out of the desire to join the modern, global economy, to become a part of affluent society. Wittenberg, like many smaller cities in the former East Germany, however, remains economically depressed. During the communist era, investment in heavy industry made a nearby chemical plant the heart of the local economy, which was modeled on large, state-planned monostructures; few small or medium-sized businesses existed. In 1989, the chemical and mining industries collapsed. These industries along with the agricultural sector have rebounded somewhat after a difficult transition to a market economy, but unemployment in the Wittenberg region hovers around twenty percent, and many young people leave the area for jobs and education in larger urban centers. The population has dropped from 68,000 in 1989 to 47,000 in 2008. In less than twenty years, the city lost twenty percent of its population. Wittenberg’s considerable cultural capital is an opportunity to tap the tourism market. People do not, of course, live by bread alone. The Wittenberg festivals are economic engines, but they are more than that: they play a role in bringing a depressed town back to life, replacing the fear, monotony, and isolation with a convivial culture, with spirit and soul. The contemporary festivals, as public events, are of and for the public; residents of Wittenberg and the surrounding region make up roughly two-thirds of those attending.

While Reformation Day is a centuries old tradition, grounded in the liturgical cycle of the German Evangelical Church, Luther’s Wedding, a Volksfest, is a new city festival inaugurated in 1994, part of local efforts to deal with these promises of prospects resulting from German reunification. The Wedding festival, which draws upwards of 100,000 visitors, has been an enormous success, stimulating economic development, cultural renewal, and an active public sphere.

Luther’s Wedding unfolds around a spine of events related to the historical wedding of Luther and Katharina von Bora, as well as contemporary wedding practices. Historically, Luther’s writing against celibacy led many monks and nuns to renounce their vows, an act that was punishable by death. At Easter of 1523, von Bora and eleven other nuns fled from the Nimbschen convent to Wittenberg. The family of Lucas Cranach aided von Bora, and she and Luther would eventually marry on June 27, 1527, after a two-week engagement. In the nineteenth century, images, books, plays, and souvenirs based on Luther’s Wedding became popular in Lutheran communities, providing a sedimented tradition upon which the contemporary festival implicitly draws.

Around a number of “wedding” activities-the arrival and welcoming of the escaped nuns, giving away the bride, the city parade in honor of the couple, the reception, the cake cutting, and closing ceremonies-is cobbled a variety of performative events: music, dance, theatre, lectures, special activities at Wittenberg’s museums, worship services, and a great deal of wandering around-a favorite German pastime. Taking in the diverse variety of events, eating, drinking, and socializing are the dominant activities. The festival’s overall kinesthetic sense is perambulatory: people stroll, socialize, greet friends and family, peruse displays, enjoy a beer in a festive setting, watch street theatre, attend a worship service or concert. Friday and Saturday nights can become raucous, and considerable time is spent Saturday and Sunday mornings cleaning up the garbage and bottles from the night before. The festival is marked by the carnivalesque-dressing up, mild forms of symbolic inversion and parody, and, as the partying on Friday and Saturday night ramps up, license. The consumption of beer and wine, the large crowd, the music, and movement through the streets push the festival to the edge of the chaotic; at the closing ceremony, officials take pride in announcing that the festival has once again been celebrated without major incident.

The “Little Tradition”

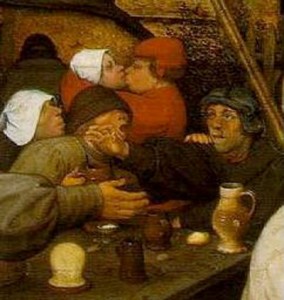

The Flemish Renaissance painter Pieter Breugel (1525-1569) captured in his works the spirit of the so-called “Little Tradition,” the daily life, games, ritual, and festive events of the lower classes of early modern-era Europe. Carnival and carnivalesque celebration were central to European social-cultural life in the late medieval and early modern eras, the result of the church assimilating the seasonal feasts of pagan culture into its rites and liturgical calendar. Carnival was the institution around which life revolved. People lived “in remembrance of one festival and in expectation of the next.”6

Carnival and Lent

In his “Carnival and Lent,” Breugel depicts the atmosphere of early modern era Carnival culture. The figure of “Carnival,” a bawdy, beer drinking, flesh eating, rotund man, sits astride a beer barrel, holding (or wielding like a lance) a pig on a spit, surrounded by festive revelers. He is pitted against “Lent,” a frail, withered old woman, carrying a bundles of switches used to scourge penitents, displaying two fish on a baker’s paddle, with the aged pious trailing behind.

Three chief themes characterized early modern-era Carnival: “food, sex, and violence.”7 For these reasons, clergy, nobility, and the refined tended to view Carnival with suspicion and derision. Carnival was the domain of the lower or middle classes, a “world turned upside down,” a time to symbolically, imaginatively invert and skew gender roles and class structures, impugn the haughtiness of religious and political elites, and get a bit ritually crazy, perhaps so as not to go really crazy. Carnival emphasized masking, costuming, processions, the over-consumption of food and drink, farcical plays and skits in the streets, music, carousing, and dance in the streets and market squares.

The bearers of society’s moral compass generally viewed indulgence in food, drink, and sex as a threat to the fiber of the folk. Those holding the reins of temporal power knew that during Carnival the horses might run wild. The agonistic satire, the ritualized violence, the burning of effigies, symbolic killings, and performance of transgression and inversion that accompanied Carnival could always threaten to turn in to the real thing. Occasionally, they did.

Carnival Versus Lent

Luther himself was relatively tolerant of popular culture, and had no major objections to Carnival: “let the boys have their games,” he would say. Lutherans, however, “were stricter than Luther,” and in post-Reformation Europe, as historian Peter Burke has shown, reformers of all stripes (Lutheran, Calvinist, and Catholic) took heavy aim at the popular practices and rites of the “simple folk.” I quote Burke at length:

The reformers objected in particular to certain forms of popular religion, such as miracle and mystery plays, popular sermons, and, above all, religious festivals such as saint’s days and pilgrimages. They also objected to a good many items of secular popular culture…. Actors, ballads, bear-baiting, bull-fights, cards, chap-books, charivaris, charlatans, dancing, dicing, divining, fairs, folktales, fortune-telling, magic, masks, minstrels, puppets, taverns and witchcraft. A remarkable number of these objectionable items could be found in combination at Carnival, so it is no surprise to find the reformers concentrating their attack at this point…. This cultural reformation was not confined to the popular, for the godly disapproved of all forms of play [including, for example, theatre]. Yet one is left with the impression that it was popular recreations which bore the brunt of the attack…. What, according to the reformers, was wrong with popular culture?…. In the first place, [as Erasmus explained] Carnival is “unchristian” because it contains “traces of ancient paganism.” In the second place [again, according to Erasmus] it is unchristian because on this occasion “the people over-indulges in license.”8

The history traced by Burke is one that sees Carnival and other forms of popular culture and religion sharply curtailed across much of Europe, especially Protestant Europe, by 1800. In North and South America, Carnival traditions thrive in such events as the New Orleans Mardi Gras and Brazilian Carnaval in Rio Di Janeiro.

In nineteenth-century Germany, Carnival traditions stubbornly persisted in pockets of the primarily Catholic southwest, but they disappeared in the Protestant northeast. France invaded southern Germany in 1794, and the Prussians invaded from the northeast in 1815. Like the church before them, these state powers worked to suppress Carnival. In the Nazi era, Carnival all but disappeared, or was strictly employed for ideological purposes: travesty, satire, parody, masking, transgression-these were anathema to the Nazis. Similarly, in communist controlled East Germany, Carnival was suppressed.

Connecting to the Past

On the cover of the Luther’s Wedding program is a digitally modified copy of Peter Breugel’s 1658 painting, “Peasant Dance.” The image is also used for large posters advertising the festival. The scene depicted is one of festive merry-making; villagers dance, play music, socialize, kiss. Superimposed on the image by Wedding organizers, centered on the background horizon, is the tower of Wittenberg’s Schlosskirche. There are four features of this image worthy of note, as the image reveals how Wittenbergers imagine transformation.

First, the poster reveals that the festival is of and for the people, the Volk, rather than the church and clergy, or the state and politicians: Luther’s Wedding is a Volksfest. Second, Breugel’s painting points to the atmosphere and style of the contemporary festivals, a mix of conviviality and the carnivalesque. Conviviality is a baseline, a foundation. The villagers dancing, playing music, and socializing in Breugel’s painting are doing so simply because these are things people enjoy. Third, the poster includes an implicit narrative. In adding Wittenberg’s Schlosskirche to Breugel’s painting, festival organizers and festivalgoers draw on cultural resources of the past to imagine and create the present. Festival culture in Wittenberg takes as its model the festive, popular culture of early modern Europe, and imaginatively, mimetically re-creates it. Last, it is important to reflect on the setting in Breugel’s painting, which has implications for understanding changes taking place in what is often called the “public sphere.” The celebrations take place in the streets, market squares, and courtyards of the old city-outside, in spaces openly public, rather than inside, in spaces associated with particular cultural spheres and specialized institutions, interests, and statuses.

Umzug (Wedding Parade)

The Wedding parade is the preeminent example of festive display in Wittenberg. Held on Saturday afternoon at two pm, the parade marks the halfway point of the festival. Costuming, artifacts, music, and dance locate the event in an imagined past, in Reformation-era Wittenberg. Participating in the parade are kindergarteners, schoolchildren, teens, adults, and seniors, representing a variety of local groups and interests: schools, music, dance, and theatre clubs. Most people in the parade are from Wittenberg and the surrounding area, but the inclusion of groups from partner cities and heritage and tourism organizations from around Europe-Germany, Italy, Denmark, and Belgium-mark the event as an international affair.

Parades are chiefly about display, and the Umzug is the residents of the city and region showing themselves to one another. The Umzug, like the larger festival, is a magnet; the parade makes Wittenberg-for a short time, at any rate-the place to be. There is a saying in German: sehen und gesehen werden meaning “to see and be seen.” Wittenberg at festival time is such a place. The colors come out, flags and banners are hung, costumes are dusted off and spruced up, stages are put together, parade floats are built, flyers are printed, fancy cakes are baked, the streets are given an extra sweeping, and the walls a fresh coat of paint. One definition of performance has it as the “showing of a doing.”9 At festival time, individuals and groups put their doings on display.The Umzug is described as the “Höhepunkt” (highpoint) of the festivities. A cast of a thousand walks the two kilometer route from the gate of the Lutherhof, looping around the old town to the Marktplatz, and then back the Lutherhof. Up to 40,000 spectators line the streets-a number just a few thousand less than Wittenberg’s population. Everyone, it seems, does love a parade.

Public Sphere

The historical trajectory of the modern west has seen the erosion of public life, the rise of an intensely interior religiosity, and the shrinking of social life to the personal domains of the family and private pursuits.10 The decay of public space and life in the modern era was magnified in East Germany. In the GDR era, public life was radically eroded as techniques of ideological control and surveillance threw the individual back onto him or herself, and perhaps a small circle of family and friends-though it was not unusual that even families would spy and report on one another’s thoughts and activities. “When everyone has everyone under surveillance, sociability decreases, silence being the only form of protection.” In public, one had to play a role (as loyal servant of the state ) that in no way could be thought of as being performed. Masks, personas, the interpersonal rites of deference and demeanor were stripped away, leaving one with a bare self. Distance, literal or metaphorical masking, and personas, argues Richard Sennet are integral to a sociable culture; “human beings need to have some distance from intimate observation by others in order to feel sociable.”11

A festival is about as sociable occasion as one can imagine, precisely because one can disappear into the crowd. No one is watching you because everyone is performing. A festival gathers people together not on the level of personal intimacy, but community and sociability. Play and jest are the paradigmatic gestures, and “jest is a piece of nonsense in the service of solidarity rather than isolation, but one which promotes fellow-feeling exactly by being an end in itself.”12 Festival culture sanctions role playing. It allows for diverse performances, creating an occasion during which citizens can present themselves and their doings to one another on a public stage, but in a framed, stylized, even conventionalized fashion (not self-revelation but self-presentation).

THE FORMER EAST GERMANY

The Stasi operated one of the most invasive systems of surveillance ever created; it is estimated that roughly one of every fifty citizens in the DDR had at one time or another served as a Stasi informant, monitoring and reporting political dissent.

It is worth noting who doesn’t appear in the contemporary Luther’s Wedding Umzug: no police, no military or paramilitary groups (other than fictional “medieval” knights and the historical “city police”), no state officials representing a more central, hierarchical authority, no political parties, and no formal group representing the church. While some of the local Vereine (associations) carry flags, the emblems of state and even municipal government are conspicuous by their absence. The didactic, ideological dimensions of military and state parades are not present in the Umzug. Rather, an event (a wedding) is celebrated, an event that allows the entire community to contribute. The parade is dominated by clubs and societies, the satirical clowning of fools, marching bands, and the quasi-royal couple Martin and Katie, framed by their entourage of “historical” folk from the Reformation era. Kinetic, colorful, slightly chaotic, filled with music, dance, performance, and art, electic and open to broad participation, the parade is a far cry from those conducted in the era of the DDR.

State organized parades were an important feature of political life in communist East Germany. Workers, youth, and sport groups would pass by a podium of party officials, carrying banners and listening to an audio track from a loudspeaker extolling the virtues of the state. Participation was organized by place of work or school, so it was easy to identify those who did not participate. The projected symbolism was a relationship of unity, loyalty, and equality between rulers and workers, wedded to a secularized sense of divine mission. But the tight proscriptions on the form and content of the parade, coupled with intense pressures to conform and participate, meant that claims of unity and harmony were largely the product of stage-managed illusion, photographed, filmed, recorded, and then re-packaged and distributed through the mass media. Above, the “Young Pioneers,” march in the streets of Berlin, 1960. The banner reads, “Victory to Socialism.” Courtesy Commissioner for Stasi Documents, Berlin. The photograph is by Hans-Joachim Helwig-Wilson.

Festival as Convivial Tool

“Tools,” writes Ivan Illich, “are intrinsic to social relationships. An individual relates himself in action to his society through the use of tools that he actively masters …. To the degree that he masters his tools, he can invest the world with his meaning; to the degree that he is mastered by his tools, the shape of the tool determines his own self-image.” Illich’s definition of a convivial tool or institution is precise: “Convivial tools are those ones which give each person who uses them the greatest opportunity to enrich the environment with the fruits of his or her vision.” Luther’s Wedding is a tool that promotes broad participation and encourages self-expression; in so doing it “enriches the environment.” [Insert gallery here?] “Conviviality,” writes Illich, is the opposite of “industrial productivity,” and the ethos of industrial productivity ruled communist-era Wittenberg. Conviviality refers to the presence of “autonomous and creative intercourse among persons, and the intercourse of persons with their environment…. [C]onviviality [is] individual freedom realized in personal interdependence and, as such [is] an intrinsic ethical value.”13

Death and Renewal

Just as carnivalesque festivity has a prominent place among contemporary public events, the term has also become part of the theoretical lingo of the social sciences and humanities, chiefly through the work of the Russian literary theorist, Mikhail Bakhtin (1895-1975). My use of the term then is not simply descriptive, but carries theoretical implications and claims. Through Carnival, writes Bakhtin, people created a “second life,” entering, for a time, a “utopian realm of community, freedom, equality, and abundance.”14 In Bakhtin’s view, convivial relations and the performance of Carnival are one and the same. Historical understandings of medieval and early modern era Carnival recognize the context of a hierarchical class system and feudal political structure. Carnival, it has been argued, was a means to suspend or alleviate tensions within these stratified relations, at least for a time-a kind of safety valve that released social pressures associated with class.

Bakhtin was living and writing in the age of the Stalinist terror and in his writings on the relationship between Carnival and feudal society, we can detect a critique of Soviet autocracy and monoculture. The hierarchical, authoritarian, even despotic cultural, political, and economic system of the former DDR suggests the relevance of applying Bakhtin’s narrative of medieval Carnival to festive celebration in post-Wende Wittenberg. Easter, when Carnival was (and is) enacted, was an annual marking and celebration of death and resurrection, so the resources existed within Carnival for processing larger social dramas. “[M]oments of death and revival, of change and renewal,” writes Bakhtin, “always led to a festive perception of the world.”15 The revival, change, and renewal of life in the former East Germany demands the creation of convivial relations, and the carnivalesque, embodied imagination, is a tool to such an end.

Mimesis – Magic

Walter Benjamin and Theodore Adorno tell us that the original Greek meaning of mimesis consists in “making oneself similar to another.”16 The stick bug looks like a stick, the killdeer feigns being wounded, the shaman becomes the first shaman. For Benjamin, in copying or imitating, “a palpable, sensuous connection between the very body of the perceiver and the perceived,” is made possible.17 Becoming something other than what one is, is the heart of mimetic behavior.

MIMESIS IS EMBODIED IMAGINATION

Magic is a power that a copy extracts from an original, or the power a copy has to influence or infect the original; thus, it involves a relationship between self and other, which is why Michael Taussig, following the thought of Benjamin and Theodore Adorno, connects mimesis with alterity.

MAGIC IS CONTACT, PRODUCING AN EFFECT, MAKING A CONNECTION TO SOMETHING OR SOMEONE THROUGH MIMETIC BEHAVIOR

Just how mimesis establishes a connection to others is, of course, a complex question. No doubt psychological, social, cultural, and biological factors are all involved. What I do know is that in Wittenberg people, as part of the effort to deal with the problems and prospects of reunification, have of late been dressing-up as their ancestors, enacting foundational myths of the city and region, and re-creating, a couple of times a year, a medieval world on the verge of tipping into the modern-and they do so out of some sort of sense that this will make a difference. We might call this magical; to borrow the language of Clifford Geertz, it certainly isn’t “commonsensical”-it is not ordinary, everyday behavior, which is to say that the quotidian, commonsensical, everyday world leaves something to be desired, and magic is, above all, driven by desire. But desire for what? Perhaps mimesis itself.

Discussions of mimicry, mimesis, and magic are, as I have hinted, often framed in a historical narrative. Benjamin and Adorno tell a “once-upon-a-time-we-were-mimetically-adept” story, as evidenced by dance, the mirroring of microcosm and macrocosm, and practices of divination based on correspondences between things like entrails and constellations, all of which they took as characteristic of “primitive” societies. The trajectory of the West, claimed the Frankfurt school critics, was characterized by a repression of mimetic relations to the world, to self, and to others. Modernity involved the repression of mimetic behavior, and then the return of it in highly controlled and organized spectacle forms: a mimesis of mimesis, an imitation of imitative behavior, the extreme form of which is fascism. For Adorno, fascism was but an “accentuated form of modern civilization which is itself to be read as the history of the repression of mimesis.”18

Festival – Spectacle

One of the defining characteristics of the genre of “spectacle” is the presence of a sharp distinction between audience and performers. “Spectacles institutionalize the bicameral roles of actors and audience, performers and spectators. Both role sets are normative, organically linked, and necessary to the performance.” Second, a spectacle is something primarily watched or observed. The actors perform the event, the spectators watch-at a distance. In festivity, in contrast, everyone is called to celebrate, together. Watching is part of festival action, but only a part. Last, to name an event as a “spectacle” is to introduce a certain suspicion or criticism-“he is making a spectacle of himself.” A festival is different. Rather than generating a sense of diffuse awe and wonder, emotions that captivate while distancing the spectator from the action (think of gladiatorial games), festivals are joyous occasions, or are meant to be so. The “genres of spectacle and festival are often differently valenced. While we happily anticipate festivals, we are suspicious of spectacles, associating them with potential tastelessness and moral cacophony.”19 The French sociologist Guy Debord argues that modernity is a “society of the spectacle,” which is to say, “an epoch without festivals.”20 The distinction here is between the production of spectacle by elites for nationalist, consumptive-commercial purposes versus a more organic, cyclical domain of festivity that emerges from a people’s productive labor.

The Modern Social Imaginary

Charles Taylor coined the phrase “modern social imaginary,” to refer to the practices of sense-making accompanying modernity. Modernity is “that historically unprecedented amalgam of new practices and institutional forms (science, technology, industrial production, urbanization), of new ways of living (individualism, secularization, instrumental rationality), and of new forms of malaise (alienation, meaninglessness, a sense of impending social dissolution).”21

What is (or was) modernity?

One answer: Modernity is the iconoclasts and bans on graven images, the persecution of gypsies, the Pietists’ closing down of theaters and opera, the Puritan’s denial of the body and dance, a smug fear of embodied religious fervor and emotionalism, the eclipse of festive, popular celebration by the ideologically driven spectacle, and, in the words of Peter Burke, the “triumph of Lent over Carnival.” Mimesis under siege.

The Contemporary Imagination

Arjun Appadurai has argued that media and mobility are constitutive features of the contemporary imagination. Both the circulation of mediated images and the movement of people allow for “ordinary people… to deploy their imaginations in the practice of their everyday lives.” Image and movement have the potential to mobilize agency, and inform “local repertories of irony, anger, humor, and resistance.” The “new power of the imagination in the fabrication of social lives is inescapably tied up with images, ideas, and opportunities that come from elsewhere, often moved around by the vehicles of mass media.” Appadurai rejects the narratives of modernization theorists who would bury the imagination in “the forces of commoditization, industrial capitalism, and the generalized regimentation and secularization of the world.” People, argues Appadurai, are not simply cogs, consumers, or skin-encapsulated egos, but agents, producers, and members of collectivities. “The imagination,” in contrast to fantasy, “is not private and individualistic.” Rather, it “has a projective sense about it, the sense of being a prelude to some sort of expression, whether aesthetic or otherwise… The imagination today is staging ground for action, and not only for escape.”22 I want to extend Appadurai’s analysis, adding a third element to the workings of the contemporary social imagination, namely, festive celebration.

Carnival Versus Lent, Again

Frank Manning, writing in the early 1980s, claimed, “throughout both the industrialized and developing nations, new celebrations are being created and older ones revived on a scale that is surely unmatched in human history.”23 Manning may have been overstating the case, but there is evidence that festive celebration in Europe and North America has experienced a renaissance.24 What is going on here? Why are cities and regions turning back to earlier forms of popular culture?

Why is the carnivalesque experiencing a revival? If we consider Peter Burke’s list of what Reformers and others went after, a common denominator is mimetic behavior: dressing-up, masking, puppets, charlatans, mystery plays, magic, role-playing. People are doing these things, once again-the return of what had been repressed. In a way, the actors and festivalgoers in Wittenberg’s streets at festival time are telling a story. In assessing the spiritual and cultural predicaments and possibilities of the present, there is an implicit understanding that the past is a relevant piece of the puzzle. To know where we stand, we have to know where we have come from. The notion of “disenchantment” developed by Max Weber to describe the spiritual condition of modernity is related to the suppression of carnival, myth, and magic in western culture. Wittenberg’s festivals are attempts at recovering and reinventing lost mimetic traditions.

The Wittenberg English Ministry (WEM) has been operating in Wittenberg since 1997. A key aim of the WEM is to provide an explicitly Lutheran confessional context to Luther-themed tourism, festivals, and heritage culture. A Renewal of Vows Ceremony, introduced by the WEM, has been part of Luther’s Wedding since 2002. During the greeting, the congregation responsively reads Psalm 100: “Shout for joy to the Lord, all the earth/ Worship the Lord with gladness/come before him with joyful songs.” The occasion is intended to be celebratory, but in both services I attended (in 2005 and 2006), I felt a distinctly ideological undertone; there is more at work in the service than praise and the reaffirmation of vows. The American founder of the WEM introduced the renewal of wedding vows service in an effort to “uplift the festival,” to “take a large beer fest, a party, and inject it with some spirituality, with some connection to Lutheran theology.” In other words, the service developed in part as a reaction of American Lutherans to the carnivalesque character of Luther’s Wedding.

For the wedding festival, two small stages for pipe and drum music are set up just outside the walls of the Stadtkirche. During the renewal service, the drumming, piping, singing, and shouting outside is so loud that it pours through the walls of the church. If the service aims to “uplift” the festival, the festive sounds of street celebration threaten to drown out the attempt. One of the most popular New Testament readings at weddings, and part of the Renewal service, is 1 Corinthians 13, the famous meditation on and celebration of love. The first line reads, “If I speak in the tongues of men and of angels but have not love, I am a noisy gong or a clanging symbol.” During the sermon, as the music and noise from outside became obvious competitors to the action inside, the American pastor commented, “I was thinking while you were reading the Corinthians section about [the] gonging cymbals that are outside of our [sic] church here. A little added emphasis for the Holy Scripture.” A good-natured laugh rippled through the congregation, but the “gonging cymbals” comment did not diffuse the palpable tension.

A few minutes later, during the middle of the sermon, the noise once again became a nuisance. The sermon was on the theme of how the good news of the gospel is the answer to dealing with whatever “crosses one’s path.” With the noise from outside obviously “crossing” the path of the service, the pastor fell into implicitly pitting the church and faith against the festive celebrations. “The church is a refuge, is a place where we can come and spend time with God and say to him, ‘Help me deal with the rest of the world that crosses my path every single day. [A world which] is loud and full of debauchery, and full of kinds of temptations out there that cross my path every single day.'” The Wedding festival does indeed become raucous, but characterizing it in terms of “debauchery,” synonyms for which include “wickedness,” “corruption,” “depravity,” and “sin,” would be considered laughable and overly puritanical by the vast majority attending the festival, including most German Lutherans. The comment set up the small group worshipping in the church as a bulwark against a sea of corruption outside. The tone of the service became defensive, as the outside noise continued to interfere with worship. The extra-ecclesiastical celebrating outside could have been framed in terms of Psalm 100-people shouting for joy, praising with joyful songs-but it was not.

Richard Schechner writes about “twice-behaved behavior” or “restored behavior.” “Restored behavior is symbolic and reflexive” and comes down to a single principle: “the self can act in/as another… Restored behavior offers to both individuals and groups the chance to become again what they once were-or even, and most often, to become again what they never were but wish to become.”25 Reformation-themed festivity in Wittenberg reenacts what the Reformation would ultimately do away with, what the people, who for centuries now have located their origins in Luther and the Reformation, never were but wish to become: the “battle” between Carnival and Lent that was medieval Carnival. Spielleute mock priests and nuns, and bring Luther down off his heroic pedestal in the Marktplatz, pillorying him with satire. Meanwhile inside the pious complain about drums and pipes, a “medieval movement” in the Marktplatz, and try to uplift Luther’s Wedding in a renewal of vows ceremony while the sounds from outside flow inside to disrupt the service. Turning to Luther as an occasion for a kind of modern, secularized magic, a drumming and dancing into being the spirit of a lost world, evidently puts some church members ill at ease!

The Spirit of the Carnivalesque

Peter Burke sees in the battles between Carnival and Lent that were performed in the streets during the carnival season “two rival ethics or ways of life in open conflict.” On the side of Lent rested the values of “decency, diligence, gravity, modesty, orderliness, prudence, reason, self-control, sobriety, and thrift, or to use a phrase made famous by Max Weber, ‘this-worldly asceticism’…. [This] ethic of the reformers was in conflict with a traditional ethic which is harder to define because it was less articulate, but which involved more stress on the values of generosity and spontaneity and a greater tolerance of disorder.”26

Charles Taylor, in reviewing various theories of Carnival, finds in them a common theme: the idea of “complementarity, the mutual necessity of opposites… of states which are antithetical, can’t be lived at the same time”-except during the periodically created and bounded times of liminal, festive celebration. Carnival-like events and moments, and their persistent presence in human cultures, indicate a fundamental individual and social need for what Turner calls “anti-structure.” The notion that a social code or order ought to leave “no space for the principle that contradicts it, that there be no limit to its enforcement… is the spirit of totalitarianism,”27 and East Germany has known, in its recent past, enough of that spirit.

In human history, I see a continuous tension between structure and communitas, at all levels of scale and complexity. Structure… holds people apart, defines their differences, and constrains their actions… [this] is one pole in a charged filed, for which the opposite pole is communitas, or anti-structure… the desire for a total, unmediated relationship between person and person, a relationship which nevertheless does not submerge one in the other but safeguards their uniqueness in the very act of recognizing their commonness. Communitas does not merge identities; it liberates them from conformity to general norms, though this is necessarily a transient condition if society is to continue to operate in an orderly fashion.28

Festival culture evokes or is underpinned by this quality of commonality or communitas that is difficult to precisely identify or describe. It is partly created by collective action, by the sociable qualities of mutual, public display. In Turner’s descriptions of communitas is a latent element of bearing witness to one’s own tastes, interests, and activities, in the context of a wider collective display. Our everyday, normative doings and identities are somewhat suspended, and our creative acts and personas, our imaginative life and our buffoonery, quirks and special talents, are given presence before and with others, and thereby validated. Such moments of common action and feeling “both wrench us out of the everyday, and seem to put us in touch with something exceptional, beyond ourselves.” Charles Taylor, whom I am quoting here, calls this the category of the “festive,” and it is inherently related to the development of a more immediate, active, face-to-face public sphere. It is also, suggests Taylor, “among the new forms of religion in our world.”29

Featured image: “Carnival and Lent” (1566) by Pieter Breugel. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna.

Notes:

- The research was funded by a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council Postdoctoral Fellowship. Aside from a couple of historical items, the images and video footage used here were shot in Wittenberg, during the Luther’s Wedding festival in June of 2005.

- My combining text, photography, and video in this “paper” raises many questions. What, for example, “can pictorial images convey that words cannot? How do film images mean?” (Quoting Jay Ruby, Picturing Culture (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994), 166). Bertrand Russell distinguishes between knowledge by acquaintance and knowledge by description. In general, academic study has deemed this former kind of knowledge to be superfluous, off-limits, or inaccessible. Visual media in scholarship have been primarily supplemental and naturalistic. The visual is a confirmation, illustration, or background to insights, observations, arguments, and theories expounded through the text. Histories of the senses tell the story of the triumph of the visual in western culture. The academic contribution to this triumph is the text. We work on texts, produce texts, and read them at conferences. We even “read” phenomena that obviously are not texts-things like temples, cock fights, cinema, and festivals-as though they are texts. For those studying the senses and cultural performance, western visualism is often a target of criticism. Steven Feld and others have focused on the centrality of sound in non-western cultures; in so doing, they have alerted us to the variety of sensory awareness in human societies. But Feld insists that this newfound awareness of the aural and other senses should not become a form of anti-visualism. What is required, Feld writes, is an integrated understanding of the “interplay of tactile, sonic, and visual senses.” See “Waterfalls of Song,” in Senses of Place, edited by Stephen Feld and Keith Basso (Santa Fe: School of American Research Press, 1996), 91-136. This is a tall order, and the desire for such an integrated approach raises the question of whether the text and the spoken word, the two conventional forms of academic knowledge, are up to the task.

The “crisis of representation” in anthropology has led to experimenting with textual forms, tropes, and styles. In part, this experiment has been driven by the desire to tend to modes of experience and knowledge not easily attainable through traditional forms of scholarly writing. It may be that there is a fundamental incommensurability between sensory experience and knowledge and the academic text; can visual, auditory, and tactile experience be conveyed through linguistic means? Perhaps innovative and experimental forms of writing will prove effective, but “as some scholars are searching for parity among the senses” we might consider a “greater parity among modes of academic expression” (Quoting David MacDougall, The Corporal Image: Film, Ethnography, and the Senses (Princeton University Press, 2006), 60). Multimedia scholarship offers a chance for experimentation.

Writing is a cumulative, aggregative medium; photography a composite medium; film is both sequential and composite. What this means is that it is well nigh impossible to convey the interpenetration of sensory domains in a text. In a text, you have to do each one at a time; in the film, the simultaneity or co-presentation of sound and image are a more faithful representation of the original sensory environment. Appearance, sound, motion, texture, volume, space-these can be perceived, in unison, through film. Like a strong smell, a film or a photograph has an immediate, brute, sensual presence that words lack. They also have a transcultural quality: everyone can look at a photograph or watch a piece of video, not everyone can read a text. If a text communicates, images and film implicate; a film implicates subject, spectator, and filmmaker-a process that favors experience over explanation. A film or image is not an unadulterated revelation of some objective reality; but it is a less conventionalized system of signification and representation then is writing. Herein rests its power for studying ritual, place, social environments, the senses, imagination, identity. This is not simply a question of new avenues of interest but of new kinds of understandings, made possible by alternate means of approach and expression. The move to expand the range of phenomena we study is based on what anthropologist Nicolas Thomas calls the epistemology of quantity. Thomas writes: “Defects are absences that can be rectified through the addition of further information, and more can be known about a particular topic by adding other ways of perceiving it. ‘Bias’ is thus associated with a lack that can be rectified or balanced out by the addition of further perspectives.” See Nicholas Thomas, “Against Ethnography,” Cultural Anthropology 6.3 (1991): 306-22. If academia has privileged the textual, tending to the sensory dimensions of social-cultural life, like tending to visual and material culture, ritual and performance, emotion, imagination, gesture, place, landscape, promises greater comprehensiveness.

- James Clifford, Routes: Travel and Translation in the Late Twentieth Century(Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1997), 12.

- The German “Wende”is often rendered into English as “peaceful revolution,” though the term literally means “change.” Wende also means turn. Thus a Novelle has a Wendepunkt. In the context of the collapse of communism, the term refers to moments of great import in history.

- Luther’s Wedding unfolds around a spine of events related to the wedding of Luther and Katharina von Bora. Luther’s writing against celibacy led many monks and nuns to renounce their vows, an act that was punishable by death. At Easter of 1523, von Bora and eleven other nuns fled from Nimbschen convent to Wittenberg. The Renaissance painter Lucas Cranach aided von Bora and she and Luther would eventually marry on June 27, 1527, after a two-week engagement. In the nineteenth century, images, books, plays, and souvenirs based on Luther’s Wedding became popular in Lutheran communities, providing a sedimented tradition upon which the contemporary festival implicitly draws.

- Peter Burke, Popular Culture in Early Modern Europe(New York: Harper Torchbooks, 1978), 179. Burke discusses the distinction between the “great” and “little” tradition, or “popular” and “high” culture (23–29). Burke brushes off Robert Redfield’s (Peasant Society and Culture, 1956) distinction between “little” and “great” traditions by correcting Redfield’s assumption that social elites did not partake in popular culture.

- Burke, 186.

- Burke, 208-209. The excerpt here is from Burke’s chapter, titled, “The Triumph of Lent: the Reform of Popular Culture.”

- Richard Schechner, Performance Theory(New York: Routledge, 2003), 114.

- See, for example, Robert Bellah et al., Habits of the Heart: Individualism and Commitment in American Life(Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996).

- Richard Sennett, Fall of Public Man(New York: W.W. Norton, 1992), 12-15.

- Terry Eagleton, The Gatekeeper(New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2001), 113.

- Ivan Illich, Tools for Conviviality(New York: Harper and Row, 1973), 11-23.

- Mikhail Bakhtin, Rabelais and his World, translated by Helene Iswolsky (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1968), 9.

- Bakhtin, 9.

- Michael Cahn, “Subversive Mimesis: Theodore Adorno and the Modern Impasse of Critique.” In Mimesis in Contemporary Theory, 27-64, edited by Mihai Spariosu (Philadelphia, John Benjamin’s Publishing, 1984), 34.

- See Michael Taussig, Mimesis and Alterity (New York: Routledge, 1993), 20-21.

- Tausig, 68.

- John MacAloon, “Olympic Games and the Theory of Spectacle in Modern Societies.” In Rite, Drama, Festival, Spectacle(Philadelphia: Institute for the Study of Human Issues, 1984), 243-246.

- Guy Debord, The Society of the Spectacle(New York: Zone Books, 1995), 113.

- Charles Taylor, “Modern Social Imaginaries,” Popular Culture14.1 (2002): 91.

- Arjun Appadurai, Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization(Minneapolis, Minn.: University of Minnesota Press, 1996), 3-7.

- Frank E. Manning, The Celebration of Society(Bowling Green, OH: Bowling Green University Press, 1983), 4.

- Jeremy Boissevain, Revitalizing European Ritual(New York: Routledge, 1992) a collection of case studies on the resurgence of traditional celebrations across Europe.

- Richard Schechner, Between Theatre and Anthropology(Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1985), 36-38.

- Burke, 213.

- Charles Taylor, A Secular Age(Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2007), 50-51.

- Victor Turner, Dramas, Fields and Metaphors (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1974), 274.

- Taylor, A Secular Age, 482-483.