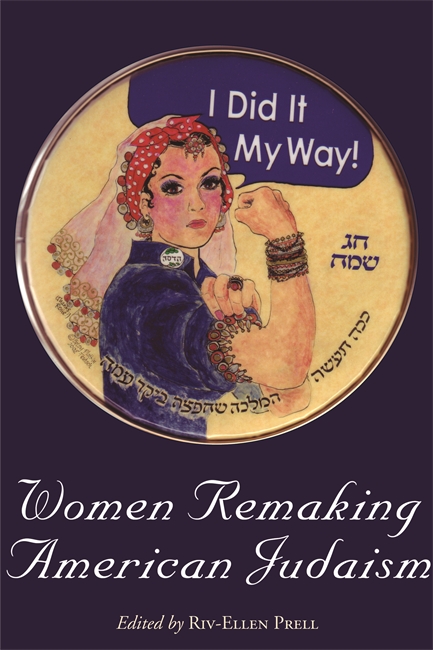

Download PDF: Prell, Women Remaking American Judaism_Prell_Imhoff–JS–Finalized–7-2-09

By Riv-Ellen Prell (Editor)

Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2007. 352 pages. $25.95.

No serious observer could deny the influence of gender on religion in contemporary America. But many scholarly treatments of women continue to be compartmentalized and often insulated from the main narratives of religious experience and history. However, in Women Remaking American Judaism, editor Riv-Ellen Prell brings alive the controversies and contributions of women in American Judaism. The volume, created from a 2004 academic conference at Wayne State University, continues the conversation about how Jewish feminism has shaped and reshaped American Jewish thought and practice.

Although only the best edited collections seamlessly integrate their selections, Women Remaking American Judaism skillfully presents one overarching yet compelling argument: if one wants to understand American Judaism, one must understand the influence of women. Without losing the specificity of the individual chapters, the volume insists that every aspect of American Jewish life has been – and continues to be – shaped by women. Prell’s introduction asserts that “Jewish feminism is best studied ‘locally,'” (3) that is, in individual synagogues, women’s groups, rituals, objects, and study sessions. Using a variety of sociological, ethnographic, and historical methods, the scholars of these focused studies highlight particular loci of Jewish women’s experiences in detail. The cumulative effect of this volume of locally focused scholarly essays is a strong sense of the transformative nature of Jewish feminism on American Jewish life.

Prell divides these studies of Jewish women’s religious contributions into three related sections. The first section explores how women are “revising” the tradition through feminist encounters with text. The second turns to how they are “redefining” what it means to practice Judaism through changing Jewish denominational life and practices. Finally, the contributions of the third section examine how women are “reframing” the relationship between Judaism and womanhood through the creation of new (or recovered) rituals. Although the authors are conscious of the history of these changes, which many trace back to the 1970s, they present Jewish feminism’s influence as an ongoing process: women “are remaking” rather than “have remade” the tradition. American Judaism is a work in progress, Women Remaking American Judaism argues, and women have been its often unappreciated workers.

The volume as a whole treats the ways feminism and feminists have worked within Judaism with nuance. Rather than presenting a kind of triumphalist narrative for either “feminism” or “Judaism,” the authors describe how women’s practices have been both radical in their challenges but also accomodationist in their compliance with community and Jewish law. In her essay on adult bat mitzvah, for example, Lisa Grant observes one of the continuing challenges for women claiming greater roles in Jewish practice: “The problem… was that as women claimed their egalitarian rights, they began to realize that they lacked the knowledge and skills to perform them” (293). One of the ways the women dealt with this problem was an accomodationist approach of increasing their knowledge and participation within existing forms and rites such as bat mitzvah. More radical approaches – like the explicit critiques offered by many of American Judaism’s first generation of women rabbis discussed by Pamela Nadell, and the demands of outspoken Conservative women described by Shuly Rubin Shwartz – also changed the way women encountered Judaism. But the volume’s strength lies in its ability to hold both challenging and accomodationist approaches together, despite the tensions between them.

Women Remaking American Judaism also represents a significant contribution to the field of ritual studies in two aspects. First, the volume offers a sustained analysis of women’s rites and ritual objects in contemporary American Judaism: the authors consider Miriam’s cup, Miriam’s tambourine, adult bat mitzvah, Rosh Hodesh ceremonies, Orthodox women’s prayer groups, and what these mean to the lives of Jewish women. Collectively these articles argue that these feminist practices and materials are not just incidental objects or epiphenomena, but they structure the ways women experience Judaism. Vanessa Ochs, for instance, highlights the primacy of ritual objects and practices in her insightful discussion of rituals and the presence of the biblical figure of Miriam. Furthermore she takes seriously the idea that the ritual objects of Miriam’s tambourine and Miriam’s cup served as the basis, or even the genesis, of certain recently popularized practices.

But the volume’s attention to religious practice extends beyond these treatments of particular rituals and ritual objects, and herein lies its second important contribution. Even the essays in the text-centered section attend to important matters of the body and religious practice. Perhaps it is because of the authors’ clear sophistication in women’s studies and feminism that such attentiveness is a priority. Regardless of the reason, the contributors consistently analyze their subject material with questions about the body and ritual in mind. For instance, Nadell’s essay considers what it means to embody the role of rabbi when one is a woman and how one uses that position to relate to a community made of women and men. Adriane Leveen explores how women encounter and form community around the Bible-based novel The Red Tent, by Anita Diamant. Deborah Dash Moore and Andrew Bush argue that Mordecai Kaplan’s rich understanding of “folkways” actually helped enable the logic and practices of Jewish feminism to take root in the Reconstructionist movement. Along with several recent monographs, Women Remaking American Judaism stands in the vanguard of seriously considering the interplay of ritual, practice, and embodiment with text and textual study in American Judaism.

Of course every volume must by necessity exclude certain topics, and one lamentable omission here is the experience of women in the generally understudied Sephardi Jewry in the United States. But Women Remaking American Judaism also contains an unexpected bonus: a timeline detailed with events in Jewish women’s history and women’s history more generally. Although the volume’s primary focus is not historical – in the sense of charting and explaining change over time – the inclusion of the timeline hints at the important stories that came before the women and the rituals described in the volume. The essays make no claim to be an authoritative historical narrative of Jewish women and feminism. Instead the authors diligently focus scholarly attention on what grammarians call the present progressive tense: “remaking,” the ongoing action of transformation. For scholars and practitioners alike, Women Remaking American Judaism should serve as a call to reconsider how feminism continues to contribute to American Jewish life.

Sarah Imhoff

University of Chicago