Download PDF: Beste, Second-Grade Children Speak

Abstract

Despite a long-standing historical debate in Catholicism about whether second grade is an age-appropriate time to receive the Sacrament of Reconciliation, there has been a virtual absence of Catholic children’s own voices and perspectives about this sacrament and its spiritual and moral effects. Joining a growing number of religious scholars who stress the need to engage in child-centered research, I conducted a qualitative study interviewing Catholic second graders about the Sacrament of Reconciliation. The purpose of this article is to analyze their drawings of this religious ritual. According to many psychologists and art therapists, children cognitively, affectively, morally, and spiritually, asking them to draw about their experiences seemed to be the most promising medium for children to express in depth what occurred during Reconciliation.

In the last five to ten years, religious scholars have begun to acknowledge their failure to attend seriously to children as a legitimate subject of academic inquiry. Influenced especially by the disciplines of psychology and sociology, many religious scholars are now recognizing that children are not passive recipients of a religious tradition but complex social actors who creatively construct meaning and have religious perspectives and experiences distinct from adults. In light of this development, there is a new level of enthusiasm about exploring religious traditions’ assumptions about children and examining children’s own perspectives about their religious, spiritual, and moral experiences. Such growing interest in childhood studies and religion is reflected in the 2002 addition of an annual group, “Childhood Studies and Religion Consultation,” at the American Academy of Religion conference, and also in an increase in publications in the last ten years about children’s participation in religious rites of passages and how they interpret these rites.1

Joining a growing number of religious scholars who stress the need to learn about children’s religious and spiritual experiences from children themselves, I have conducted a qualitative research study that explores how Catholic second graders interpret their first experiences of a particular religious ritual—reception of the Sacrament of Reconciliation. My interest in this research study was sparked after I finished a separate research project analyzing the Catholic Church’s historical and contemporary perceptions of children’s capacity to sin. I discovered that throughout the 20th century, disagreement persisted among Catholic clergy, educators and theologians about children’s moral capacities and whether receiving the sacrament in second grade teaches children effectively about sin and enhances their moral agency. Despite a post-Vatican II debate among clergy and religious educators about whether second grade is an age-appropriate time to receive the Sacrament of Reconciliation,2 Catholic children’s own voices and perspectives about this sacrament and its spiritual and moral effects on children have been a virtually absent. No research studies have been conducted to determine the effects of this sacrament on children’s moral and spiritual development or even whether, as some educators have argued, the Sacrament of Reconciliation might psychologically harm second graders.

The purpose of this article is to describe my qualitative research study and analyze Catholic second graders’ drawings of their experience of this religious ritual. Prior to interviewing the children individually, I asked the children during their religion class following the Reconciliation service to draw a picture of their experience of the Sacrament of Reconciliation. I kept this request open-ended and vague to avoid influencing their drawings. I have kept my interpretation of the drawings to the minimum in this article because I am wary of imposing my own interpretation onto the children’s drawings. I tend to interpret individual drawings only when the child offered a verbal interpretation of his or her drawing or confirmed a comment I made about his or her particular drawing.

Methods

During the 2006-2007 academic year, I received approval from three Catholic elementary schools to observe five second grade religion classes as students prepared to receive the Sacrament of Reconciliation. I visited each religion class once per week for six to eight weeks. During my first visit, I introduced myself to the students and explained that no researcher had ever asked kids like themselves what it was like to receive this sacrament. I explained that I wanted to learn about their ideas and questions as they prepared for the sacrament, and that I would like to interview them after they received the sacrament. I sent parental informed consent forms home with the children and asked them to talk to their parents about whether they wished to participate in the study; if they decided that they would like being interviewed, they could return the forms to their teacher. Besides being interested in learning how second graders themselves were introduced to the themes surrounding this particular sacrament, the purpose of my class visits was to get to know the students and establish a rapport so that they would be comfortable talking to me during the interviews.

After attending the Reconciliation prayer services, I interviewed 74 children, all of whom returned their parental informed consent forms and assented to being interviewed. In my qualitative research study, I was interested in several key questions. First, I wished to explore children’s accounts of their overall experience of this sacrament and what meanings it has for second graders. Second, I wanted to examine second graders’ reflections on the effects of this sacrament: does this sacrament significantly alter children’s sense of self, their moral agency, and their relationship with God and others? Third, I wanted to gain insight into how second graders perceive their decision to receive the sacrament: do they view their decision as an act they freely choose and desire and/or as an act that reflects their desire to conform to the expectations of parents, teachers, peers, and/or the priest? It was my hope that asking these questions in a semi-structured interview format would offer second graders rich opportunities to express their religious needs, their view of God and relationship with God, and their sense of themselves as moral agents. I completed and later transcribed 74 interviews from these five religion classes, and each interview typically lasted 15-25 minutes. When analyzing the interviews, I used Carl Auerbach and Louise Silverstein’s method of qualitative analysis, which consists of five distinct steps for interpreting transcribed interviews: 1) highlight the relevant text from the transcribed interviews, 2) identify repeating ideas in the relevant text, 3) organize repeating ideas into themes, 4) organize the themes into more abstract ideas called theoretical constructs, and 5) organize the theoretical constructs into a narrative.3

There are a number of limitations to this study, and one obvious shortcoming is its homogenous student sample: all but one of the second graders were Caucasian and were from families that could afford private or parochial school tuition. As a result, this study cannot analyze whether race and/or class significantly affects second graders’ interpretations of their experiences of this sacrament. I hope to interview a more diverse sample of second graders in the future.

Significance of the Drawings during the Interviews

Since very few religion scholars and sociologists have interviewed children as young as seven about their religious experiences,4I conducted a broader literature review on the most effective ways to interview children. I was struck by how many psychologists and art therapists emphasize that children tend to have an easier time expressing themselves through art than through words. Art educator Brenda Engel argues that children capture how they think, feel, and visualize through the medium of art.5 Art, then, allows a researcher to uncover not only what children cognitively think about their experiences, but also how they feel and what they value about the experience. According to psychologist Marvin Klepsch and educator Laura Logie:

A drawing captures symbolically on paper some of the subject’s thoughts and feelings. It makes a portion of the inner self visible. The very lines, timidly, firmly, boldly, or savagely drawn, give us some information. More is revealed by the content, which is largely determined by the way the subject, consciously or unconsciously, perceives himself and significant other people in his life.6

In his work Their Eyes Meeting the World, psychiatrist Robert Coles emphasizes how important children’s artistic drawings have been when interviewing children about their moral and spiritual lives:

Over the past thirty years I have been constantly impressed by the expressiveness in children’s drawings, but also by their pointed connection to the circumstances of the young artist. What is significant in the life of a child comes across again and again in the drawings or paintings that child makes—more so, in my experiences, than is the case with much of what passes for (verbal) “communication” or an “interview.”7

In her ethnographic research on Catholic second graders’ experiences of First Communion, Susan Ridgely also found that children enjoyed drawing about their experiences, while verbally articulating what they experienced was much more difficult.8Because I was interested in exploring how this sacrament impacted children affectively, cognitively, morally, and spiritually, asking them to draw about their experiences seemed to be most the promising medium for children to express in depth what occurred during this religious ritual. As Marvin Klepsch and Laura Logie state, “Drawings…dig deeper into whatever aspect is being measured; and they seem to be able to plumb the inner depths of a person and uncover some of the otherwise inaccessible inside information.”9

Four out of five teachers agreed to my request to ask the children to draw a picture of their experiences of Reconciliation a day or two after the Reconciliation service. As one can see from the drawings, it is apparent that teachers encouraged children to take as much time as they needed to express artistically what Reconciliation was like for them. The primary purpose of this article is to analyze what the drawings convey about children’s experience of Reconciliation. Since children were asked to draw what their overall experience of the sacrament was before I asked them specific questions, they were free to express through their drawings what was most salient to them about their religious experience. For this reason, the drawings the children created prior to the verbal interview are a key component to understanding how they interpreted their experience and what was most important to them.10

I began each interview by asking the second grader to explain his or her drawing. Besides the fact that art often enables children to express their experiences more easily and creatively than words, another advantage to beginning the interview with the child’s drawing was that it clearly established the child as “expert” on the drawing and his or her experience of this sacrament. Most children did not elaborate in much detail about their drawings during our interviews, and they usually began to talk about how they felt before, during, and after the sacrament. In hindsight, I wish that I had spent more time at the beginning of the interview studying their drawing and asking more specific questions. My focus, instead, was on establishing a good rapport with each child, and when I gauged that the child was finished explaining the drawing and that he or she was comfortable talking to me, I moved on to additional questions about how the sacrament impacted them and why they decided to receive the sacrament.

Studying the drawings after I finished the interviews, I was struck by the great variety of themes present. Most second graders took their drawings in one of the following directions: 1) they drew a picture emphasizing the emotions they experienced during the sacrament; 2) they emphasized a certain component of the sacrament; 3) they emphasized the prominent role of the priest in the drawing; 4) they drew a picture expressing the meaning of the sacrament; and 5) they focused on the importance of their family within the context of this religious ritual. Throughout this paper, I have organized representative drawings according to these five themes. Lastly, I have included several drawings of non-Catholic second graders who learned about the Sacrament or attended the Reconciliation service at their Catholic school. These students explicitly asked me to keep their pictures, and one even asked me to interview her about what it was like to learn about the sacrament in her religion class.

Emotions Prior to, During, and After the Sacrament of Reconciliation

When asked what the Sacrament of Reconciliation was like overall, the majority of second graders (62 out of 74) frequently referred to their anticipation of the event and reported feeling excited, nervous, and/or scared. When asked why they felt nervous and/or scared, students offered the following reasons: they were nervous about sitting next to the priest and confessing their sins; it was their first time receiving the sacrament and they did not know how they would feel or what to expect; and they were worried they would forget one or many of the components of this sacrament and “mess up.” While the vast majority of second graders expressed feelings of nervousness and anxiety prior to the sacrament, their experiences during and after the sacrament became more diverse. Three overall responses emerged, which I later categorized as “lukewarm to negative,” “positive,” and “very positive.”

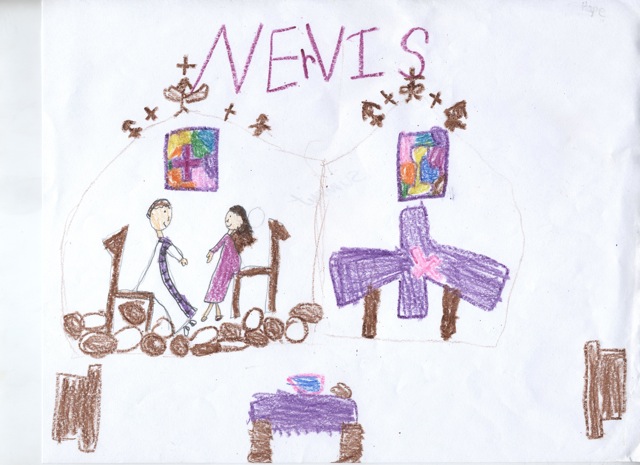

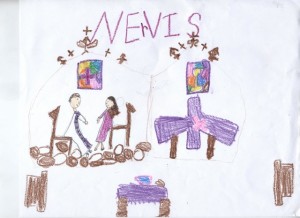

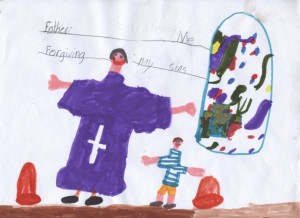

A minority of second graders (23%) emphasized feeling nervous or scared prior to the sacrament and did not volunteer how they felt after the sacrament. When asked specifically how they felt afterwards, they used bland words like “pretty good” or “good” or said they forgot how they felt. Taking into consideration nonverbal cues such as facial expressions and gestures as well as their responses to subsequent questions, I categorized these second graders’ experiences of the sacrament as “lukewarm to negative.” In drawing #1 and drawing #2 the artists reported feeling scared or nervous.

When asked how they would explain this sacrament to their peers, some of these “lukewarm to negative” students said they would tell second graders to “just do it and get it over with” or that they just have to “do this” if they wanted First Communion.

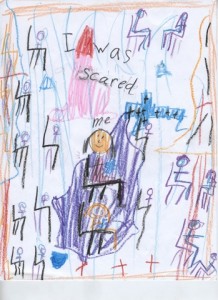

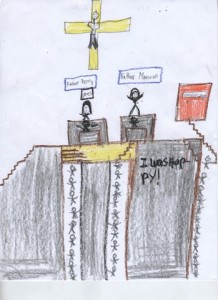

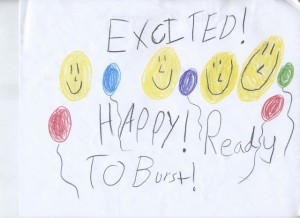

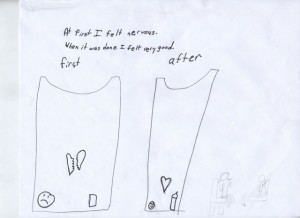

In contrast to the “lukewarm to negative” group, 57% of second graders reported a positive experience and 22% reported a very positive experience of the sacrament. One of my first impressions when beginning the interviews was the degree of joy and happiness present in many of the children’s drawings. When I commented on this, these second graders enthusiastically confirmed that it had been a joyful, exciting, or happy experience. Some used creative expressions in an attempt to capture how they felt after receiving the sacrament, such as, “I felt like I could get up and jump to the sky!” Before beginning the interviews, I had been immersed in research literature on adult perceptions of the sacrament and was struck by the contrast between many adults’ negative recollections of the sacrament and the degree of joy many of the children expressed.11 There were several drawings contrasting how they felt before and afterwards, as depicted in drawings #3-4.

Many drawings focused on feeling very happy, as shown by drawings #5-9.

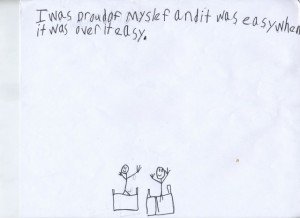

And several students explicitly talked about how proud they felt after the sacrament, as shown in drawing #10.

When asked why they felt so good and happy, most second graders stated that it was because they were forgiven for all their sins and felt joyful about being completely sinless. Cody stated: “[I felt] very happy and joyful because my body was rid of all my sins.” Tyler said: “I felt good inside because when I sinned against God I did bad stuff and then I got cleansed.” When I interviewed Megan,12 the artist of drawing #7, I asked her why she drew so many happy faces and balloons on her picture. She responded: “I drew how I felt during Reconciliation—I felt happy.” I continued: “And you write, ‘Ready to burst.’ What does that mean?” Megan promptly answered: “Well, it kind of means like woooo, kind of like jump up and pull out your hair.” I asked: “Because you were that happy?” Megan stated: “Yeah, I was really happy and excited. I was shaking all over. I was nervous.”

When interviewing the “very positive” second graders, I was often caught off guard by the degree of joy and enthusiasm these students expressed when reflecting on what it was like to receive the sacrament. Marissa simply said the day she received the sacrament was the “best day of my life.” Brian captured his rich emotions during the sacrament in the following way: “I felt like ‘Hey, I’ve been forgiven. I’ll go give my penance and then don’t do the sins ever again.’ My stomach was jumping up and down at the beginning and end. Because it was nervous then happy.” When asked to describe his least favorite part of the entire experience, Brian paused, looked directly into my eyes, and said, “Leaving the Sacrament.”

Many of these students also differed from their “positive” peers in the rich ways they describe encountering God in the sacrament. Some students like Sara explicitly mentioned feeling the Holy Spirit’s presence during the sacrament: “[I felt] really happy because the Holy Spirit is inside me. I could feel it.” Hunter echoed the comments of several of his peers when he expressed a desire to return to the sacrament: “I asked my mom if I could do it again. … I felt happy. I was so sinless, I just felt happy.” Rachel experienced intense gratitude and a strong sense of being part of something larger than herself: “I felt a lot holier. I felt I was more in God’s family. I felt it after and when he put his hands on my head. I did my penance and I kneeled and started praying and thanking God for my life.”

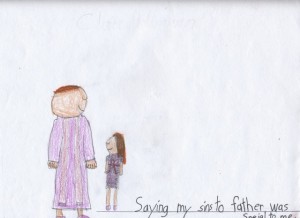

Components of the Sacrament

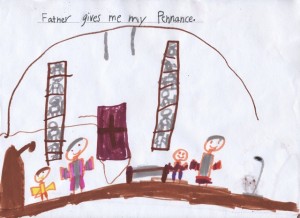

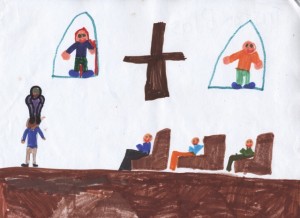

Many second graders in their drawings focused on different components of the sacrament as their way to express their experiences. Some drew pictures of what the event looked like, as depicted from the pews where they sat. In drawing #5 and drawing #11, one can see that children lined up in rows to receive the sacrament individually from priests and then stood with the priest on the altar of the church.

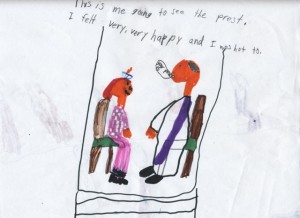

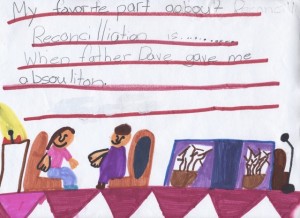

In drawing #12 a girl draws a picture of herself and the priest sitting as she received Reconciliation.

She places crosses behind the priest, perhaps representing how he is representing the power of Christ, and hearts behind herself. A significant percentage of second graders drew themselves confessing their sins to the priest, as depicted in drawing #13 and drawing #14.

In drawing #15, the artist emphasizes how nobody hears you as you confess your sins.

In interviews with the children, I was struck by how important it was to them that the priest would never reveal their sins to anyone. None of the children revealed in interviews with me what sins they confessed, and some emphatically informed me at the beginning of the interview that they would not reveal their sins. Second graders’ particular sins were fiercely private matters. In their drawings, a significant number of second graders also emphasized receiving a penance from the priest in their drawing (drawings #16-17).

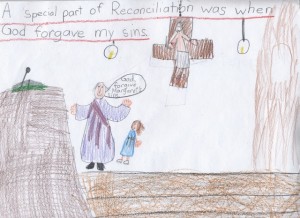

Drawings #18-21 demonstrate the moment in which the priest forgave them and absolved them of their sins.

A significant percentage of students drew pictures of the priest absolving the child of sins by placing his hands on the child’s head; this gesture was a powerful part of the ritual for many second graders.

The Meaning of the Sacrament for Second Graders

Out of all of the concepts involved in this sacrament, what struck many second graders and captured their imaginations most vividly was the power of the priest or God to forgive all of their sins completely, even the ones they forget to mention. In drawing #22 the artist draws God forgiving her for her sins as the priest prays.

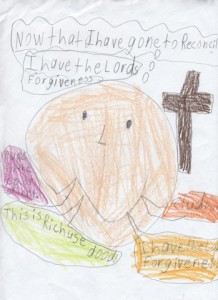

In drawing #23, the second-grade boy expresses how he experiences God’s forgiveness and depicts himself saying, “This is righteous, dude!”

Many second graders interpreted the sacrament as wiping away their sins and purifying their souls and hearts in one dramatic moment as the priest absolved them from their sins. Drawing #24 shows how black spots on the artist’s soul became completely white and pure; she also draws her heart as happy and depicts herself as celebrating the treats and party after the Reconciliation service.

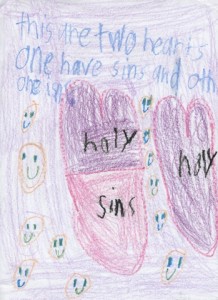

In drawing #25, the artist draws his heart as divided between being holy and sinful prior to Reconciliation, whereas his heart is completely holy after Reconciliation.

During our interview, he explained: “This one is all holy. God forgives you and the sins just disappear. All the holy stuff stays in your heart and spreads out. I felt happy that God understands that I didn’t mean the sins and He forgave me.” On the back of his picture, he wrote: “The Sacrament of Reconciliation feels good. I love God.” In drawing #26 the artist draws the stole she wore during her Reconciliation service which depicts a broken heart, an unhappy face, and a burnt out candle.

She expresses in her drawing that she felt nervous prior to the sacrament but afterwards felt very good. After being absolved from her sins, the second grader turned the stole around, with the other side of the stole depicting a complete heart, a happy face, and a lit candle. Drawing #27 also expresses the feeling of purification, with the artist stating that her “heart felt clean.”

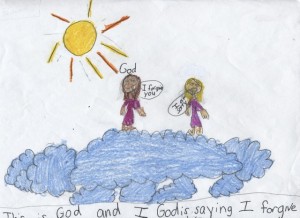

In drawing #28, the artist interprets herself as being with God in heaven when experiencing Reconciliation, expressing the joy of being forgiven.

The Powerful Role of the Priest

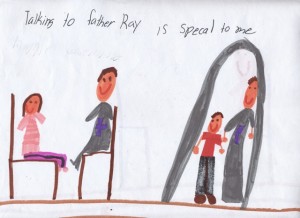

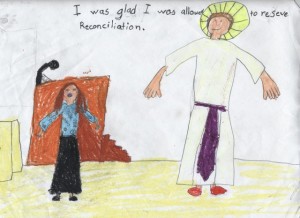

Many of the drawings also captured how powerful and important the priest was to the children during this sacrament. In drawings #29-32, the artists express how special the priest was to them during the sacrament.

My overall impression from the interviews is that the sacrament can be a powerful bonding moment with a priest for many children. For instance, the artist in drawing #32 expresses that he felt closer to the priest and the Church after receiving Reconciliation. In the picture, the priest places his hands on the child’s head and is saying, “I azove (absolve) you from your sins.” Other pictures focused on how the priest represented Jesus or God and powerfully helped them connect to God and Jesus during the sacrament. In drawing #33, the artist draws herself sitting with the priest, and Jesus standing behind the priest. She writes, “I felt like the priest was taking the place of Jesus.”

Likewise, in drawing #34, the artist is content to simply write: “I was happy because I felt the priest was Jesus.”

In drawing #35, the artist draws God or Jesus behind the priest as the priest “upzalls,” placeing his hands on the child’s head and absolving the child of his sin. God is also present high up in the picture, holding baby Jesus and saying, “This is my son.”

In drawing #36, the artist draws herself with a happy face, stating, “This is great!”

On the back of the page (drawing #37), she draws a large happy face of Jesus, communicating his joy during the sacrament.

Likewise, in drawing #38, the artist draws herself with Jesus when describing what it was like to experience Reconciliation.

In drawing #39, the artist draws a picture of herself and writes that she felt God in her heart during Reconciliation.

The Importance of Families within the Reconciliation Service

A significant percentage of children mentioned their families at some point during our interview, and it was clear that their families were an important part of their experience of Reconciliation. Some children reported how they liked having all of their family members receive Reconciliation during the service, with some stating that it gave them more courage. Drawing #40 shows the happiness of a child who just received Reconciliation, his parents and sibling happy and with outstretched arms.

In drawing #41, the artist draws his whole family and others together praying that they are sorry to God.

Non-Catholic Students’ Experience of Learning about Reconciliation

In two of the Catholic schools where I conducted interviews, there were a number of non-Catholic students who learned about this sacrament and attended the Reconciliation service. In one school, half of the students were not Catholic, and they went to a separate religion class that did not focus on preparing for Reconciliation. These students did, however, participate in the Reconciliation service; they were in charge of the singing and prayers and also acted out the story of the Prodigal Son. These second graders also drew pictures for me of their experience of the Reconciliation service and many specifically told me they wanted me to keep their pictures. I was struck by their joy and excitement during this religious service. In drawings #42-44, these students share their own experiences of the service. In drawing #42, the artist expresses his happiness at seeing his friend receive Reconciliation.

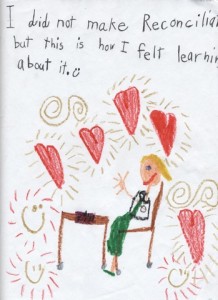

At another Catholic school, there were only a few non-Catholic students in the religion classes, and they learned about Reconciliation along with their Catholic peers. They were invited to the Reconciliation service and were invited to receive a blessing from the priest. Even though the teachers only distributed consent forms to the Catholic students and explained that I wanted to interview students who experienced the sacrament, two of the non-Catholic students told their teacher that they wanted me to interview them about their drawing and their ideas of Reconciliation. I was struck by how enthusiastic and happy these children were about Reconciliation. The artist in drawing #43 draws a picture of herself smiling and draws hearts surrounding her. She writes, “I did not make Reconciliation but this is how I felt learning about it.”

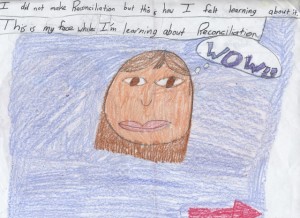

When I asked the artist of drawing #44 why she says “Wow!” in her drawing, she responded: “I got to learn how much God and Jesus loved and cared about us and how they were going to forgive us from our sins.”

Interestingly, even though they did not receive the sacrament because they were not Catholic, I did not sense from any of the non-Catholic students any feelings of exclusion. My impression from talking to non-Catholic students at these two schools and studying their drawings was that they valued learning about God’s forgiveness and desire for Reconciliation with them; they trusted that God forgave them, too, even though they had not received the sacrament.

Conclusion

This qualitative research study offers insight into Catholic second graders’ interpretations of their religious experiences and how they construct religious meanings about a significant religious ritual in their lives—meanings that do not simply correspond to their textbooks’ or teachers’ answers. As I study these second graders’ drawings and my interview transcripts, I am continually struck by the great diversity of experiences and interpretations that second graders express through their drawings about this religious ritual. When comparing their reflections during interviews with my ethnographic fieldnotes of religion class discussions and the main themes of their textbooks, it became clear that second graders were not merely absorbing and parroting back the meanings offered by their teachers and textbooks. During class, teachers reinforced the Catholic textbooks’ emphasis on what our response to God’s forgiving love in Reconciliation should be: just as we receive God’s love and forgiveness, we are called to be peacemakers, forgive others, reconcile relationships, and spread Jesus’ peace to others. In contrast to this relational meaning of the sacrament, most second graders in my study were impressed with the sacrament’s ability to wipe away all of their sins in one dramatic moment. This experience of one’s soul being purified and feeling reborn, in turn, caused many second graders to feel closer to God. Their actual focus, then, was primarily on a dramatic experience of purification and its impact on their relationship with God.

Furthermore, my analysis of these 74 interviews and the children’s drawings strongly suggest that some second graders have profound spiritual experiences during this sacrament—an idea that might surprise a significant number of religious educators and priests I interviewed who doubted children were mature enough to truly understand and benefit from the sacrament. My experiences interviewing Catholic second graders and analyzing their drawings lead me to conclude that many of these second graders had profound religious and spiritual experiences during the Sacrament of Reconciliation and are quite articulate when offered the chance to draw and reflect upon their experiences with adults who take their experiences seriously. It is my hope that my analysis of their drawings and interviews contributes to the growing body of literature by religion scholars who are beginning to explore how children from various religious traditions interpret their religious, spiritual, and moral experiences. Ethnographic research that includes participant observation, interviews, and children’s artwork are essential if religion scholars and other adults hope to shed light on the phenomena of children’s experiences. Such ethnographic fieldwork raises rich theological and ethical questions about how children are viewed, treated, and socialized within the context of particular faith communities.

Religious communities also have much to learn from ethnographic research on children if they wish to honor children’s religious insights, maximize children’s untapped potential to be religious and moral witnesses, and reveal the presence of the sacred in unique and powerful ways. Moreover, ethnographic research can help faith communities improve the efficacy of their faith formation programs. In regard to Catholicism’s current pastoral practice of preparing all second graders to receive the Sacrament of Reconciliation, this qualitative research study found that children have diverse and varied experiences of this sacrament.

Let us return full circle to the question that prompted my research project: “What insights do we gain from second graders themselves about whether this sacrament in second grade fosters or harms their relationship with God and their moral and spiritual development?” What light can second graders themselves shed on the debate about when Catholic children are developmentally ready for, and will benefit from, the Sacrament of Reconciliation? Second graders’ diverse experiences suggest that the most important variable may well be each child’s readiness and desire for the sacrament. While more research is needed to determine fully the reasons why a child has a lukewarm to negative, positive, or very positive response to this sacrament, certain comments made by the lukewarm to negative group suggest that a sense of coercion (a sense that one “has” to receive the sacrament prior to First Communion) or lack of a desire for the sacrament correlates with a lukewarm to negative experience. While none of these second graders reported blatant harm or a negative impact on their relationship with God, it is possible that their anxiety about receiving the sacrament and lack of positive affect during and after the sacrament may negatively affect their faith and relationship with God in subtle ways. At the very least, in my study, second graders’ lukewarm to negative experiences call into question the adequacy of the Catholic Church’s increasing insistence over the last thirty years that second graders receive Reconciliation prior to First Communion. If my qualitative analysis is representative of many second graders’ experiences, a correlation likely exists between a choice for the sacrament (perceiving oneself as choosing the sacrament for a constructive reason) and a positive experience of the sacrament. If this correlation does exist, it casts doubt on the wisdom of the Catholic Church’s current policy, which prioritizes conformity and unity (the normative expectation that all second graders receive Reconciliation prior to First Eucharist) over attention to the individual readiness of each child when discerning the appropriate timing of this sacrament. If the purpose of this sacrament is to experience a grace-filled encounter with a forgiving God, the priority for the Catholic Church should be to foster children’s moral agency: second graders should be invited to receive this sacrament, but there should be a space for the child to decide to whether or not to receive the sacrament, a space to own this important religious decision. This will enhance children’s developing moral agency and help them prepare for a positive encounter with God during the sacrament.

Notes

- Don Browning and Bonnie Miller-McLemore, Children and Childhood in American Religions(New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 2009); Marcia Bunge, ed., The Child in Christian Thought (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2001); Bonnie J. Miller-McLemore, Let the Children Come (San Franciso: Jossey-Bass, 2003); Bonnie J. Miller-McLemore, “Religious Rites of Passage,” in The Chicago Companion to the Child, ed. Richard Shweder (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, forthcoming); Joyce Mercer, Welcoming Children (St. Louis, Missouri: Chalice Press, 2005); Jean Holm with John Bowker, eds., Rites of Passage (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1994); Charlotte E. Hardman and Susan J. Palmer, eds., Children in New Religions (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1999); Susan Ridgely Bales, When I Was a Child: Children’s Interpretations of First Communion (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005).

- Robert O’Neil and Michael Donovan, Children and Sin(Washington, D.C.: Corpus Books, 1968); Otto Betz, Making Sense of Confession (Chicago, IL: Franciscan Herald Press, 1968); Gerald Kelly, “Notes on Moral Theology,” Theological Studies 24:4 (1963): 626-651; John Wright, “The New Catechetical Directory and Initiation to the Sacraments of Penance and Eucharist,” Homiletic and Pastoral Review (December 1971): 7-24; Francis Buckley, “First Confession: Before or After Communion?” Homiletic and Pastoral Review (April 1972): 49-56; “An Inadequate Response,” Origins 3:8 (1973): 120; “Baltimore-Washington/Regional Guidelines,” Origins 3:10 (1973): 157; “Davenport/Ministry to Children,” Origins 3:10 (1973): 159; “Introducing Children to Penance,” Origins 3:32 (1974): 490-494; Francis Connell, “Answers to Questions,” The American Ecclesiastical Review 151 (1964): 268-9; “A Reminder of God’s Love,” Origins 3:8 (1973): 118-119; Francis J. Buckley, Growing in the Church (Lanham: University of America Press, 2000); John Hardon, “First Confession: an Historical and Theological Analysis,” Eglise et Theologies 1 (1972): 69-110.

- Carl Auerbach and Louise Silverstein, Qualitative Data: An Introduction to Coding and Analysis(New York: New York University Press, 2003).

- A notable exception is Susan Ridgely Bales’s work, When I Was a Child: Children’s Interpretations of First Communion(Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005). Bales conducted ethnographic fieldwork observing Catholic second graders as they learned about the Sacrament of Reconciliation and First Communion. In her discussions with the children after they received First Communion, they sometimes spoke about their interpretations of Reconciliation. See also Susan Ridgely Bales, “Decentering Sin: First Reconciliation and the Nurturing of Post-Vatican II Catholics,” Journal of Religion86:4 (2005): 606-634.

- Brenda Engel, Considering Children’s Art(Washington D.C.: National Association for the Education of Young Children, 1995), 18.

- Marvin Klepsch and Laura Logie, Children Draw and Tell(New York: Brunner/Mazel, 1982), 6.

- Robert Coles, Their Eyes Meeting the World: The Drawings and Paintings of Children(Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1997), 7.

- Ridgely Bales, When I Was a Child, 65.

- Klepsch and Logie, Children Draw and Tell, 11.

- Before beginning each individualized interview, I explained to each child that I was interested in what it was like for them to receive this sacrament. I explained that I was going to tape record and later transcribe the interviews. I promised that no one, not even their teacher or parents, would know what they said during the interview. I also told them that I would not use their names if I included their drawing of the sacrament or a quotation from their interview in an article or book. I then asked children to sign an assent form stating that they were willing to be interviewed and understood that it was okay to decide not to answer all of my questions and/or stop the interview at any time. Lastly, I emphasized that there were no right or wrong answers to my questions. I wanted to know what they honestly thought and felt about their experiences of the sacrament.

- See A.J. Bacevich, “Memoirs of a Catholic Boyhood,” First Things78 (December 1997): 30-34; Mary McCarthy, Memoirs of a Catholic Girlhood (New York: Harcourt, 1957); Martha Manning, Chasing Grace: Reflections of a Catholic Girl Grown Up (New York: Harper San Fransisco, 1996); Gary Tobin,Saints and Sinners: The American Catholic Experience through Stories, Memoirs, Essays, and Commentary (New York: Doubleday, 1999).

- All names are pseudonyms to protect the confidentiality of the interviewees.