Download PDF: Sabine Henrichsen-Schrembs and Peter Versteeg

ABSTRACT

While the study of alternative spirituality in postindustrial secularized societies is growing, researchers lack systematic tools to describe and analyze the behavior of adherents. In a qualitative study of yoga practitioners in Germany, a typology was developed for understanding and categorizing the motivations of participants in yoga practice, resulting in the construction of four different types. Subsequently, the authors of this article explore the use of this yoga practice typology for other types of alternative spirituality. It is argued that the typology can be applied to these other forms too, as illustrated with an example of Christian holistic spirituality.

Introduction

I think [yoga] is surely also something spiritual. But that is something that, that, eh, I can’t describe well. I feel it, uhm, but, uhm, hmmm-Yes, hmm. Well this-what was just going through my head, what [the yoga teacher] often says, ‘the golden cloud of light, which surrounds you,’ right? I think that that’s a very beautiful image, and, uhm, it sometimes feels, when I am sitting there, as if I was indeed covered in a golden cloud of light, and . . .

Angelika, a woman in her late fifties, has been practicing yoga regularly for the last five years. She says that, for her, yoga exercises were never about physical fitness; rather, she was interested in its meditative and breathing techniques. The yoga practice helps her to find an inner unity, which she defines as increasingly realizing her true self, i.e. developing what is inside her (certain aspects of herself that she has not attended to) by learning to listen to her needs and desires. Yoga helps her foster this type of introspection and personal growth, although she is not really interested in the theoretical background of yoga. Still, the effect of doing meditation is such that it helps her work on her personal issues-without that explicit theoretical knowledge. Yoga is a growing phenomenon of mind, body, and spirit, and like Angelika there are others who find that practicing Yoga can help to improve their beings.

Interestingly, Angelika sees parallels between practicing meditation as part of yoga and the meditative aspects of the Protestant church service that she is heavily involved in. Angelika says that she is somewhat wary of those parts of the yoga philosophy that talk about reincarnation-somehow there is a bit of a resistance within her towards these yoga ideas, ideas which she describes as a bit “foggy.” Still, she considers yoga to be something spiritual, but she finds this aspect difficult to describe. For example, she does experience a sense of the divine when she practices yoga and imagines herself being “wrapped in a golden cloud made out of light”-an image that her yoga teacher frequently uses in the class. In this sense it seems that the yoga practice, though Angelika is a bit uncomfortable with parts of the philosophy, supports her in her own religious belief; it is another form of experiencing the “spiritual,” which is the same for her as the concept of god she resonates with as part of the Protestant tradition. Angelika shows one way in which people practice yoga. She makes use of the yoga practice in a selective way, slowly getting used to yoga philosophies; though she is not sure yet what to do with them, she is at the same time comparing the new experience to certain experiences she has had in a Protestant church service.r

In the study of alternative spirituality there are few attempts to describe systematically the motivation of participants.[1] An important exception is the typology developed by Heelas, in which he describes a spectrum of practitioners ranging from the leisure-timer and the part-timer to the full-timer.[2] Henrichsen-Schrembs was inspired by this typology to develop her own classification of yoga practitioners.[3] If we assume that, in many ways, religious behavior has changed from the kind of routines and practices related to institutional mainline religion, e.g. Christianity in its Catholic and Protestant forms, we may assume that the motivation to participate in forms of alternative spirituality has likewise changed. The most dramatic change is that the relationship between participant and spirituality is really one of choosing and buying spiritual services rather than participating in particular services because one belongs to a particular religious group. In alternative spirituality the interests and needs of practitioners are central. Potential practitioners are addressed as individuals in search of a certain kind of wellbeing.

The typology that Henrichsen-Schrembs developed aims to describe and categorize the motivations of yoga practitioners. In a qualitative study of yoga in Germany, the author found that yoga practitioners could be divided into four different types. These types are the Pragmatist, the Explorer, the Self-Helper, and the Mystic.[4] They are structured according to participants’ spiritual involvement in yoga: less involved people use yoga as a means for relaxation whereas a high involvement implies that people choose yoga as part of a lifestyle and worldview. The above-mentioned case of Angelika illustrates the type of the Self-Helper. Following Henrichsen-Schrembs’ typology, we argue that through such a classification more can be understood about how people negotiate spiritual market and thus we will be able to explore the motivations of participants more systematically. Therefore, in this article we will widen the use of the yoga typology to include other forms of alternative spirituality, illustrating this expansion by the case of Christian spirituality. We will show how forms of contemporary spirituality, coming from different religious traditions, dynamically create different motivations among their practitioners. In addition, we will argue that these forms are more likely to give room to and encourage the development of particular types over others by catering to the different religious motivations of participants. We suggest that this typology can be used as a comparative tool for the categorization of people’s motivation to practice various forms of alternative spirituality.

In this article we make a distinction between the terms religion and spirituality: religion takes place within an institutional setting (such as the church), while spirituality goes beyond such a frame. This differentiation is based on Heelas and Woodhead’s typology of forms of religious expression.[5] In short, they distinguish between three types: 1) religions of difference, 2) religions of humanity, and 3) spiritualities of life. Religions of difference primarily emphasize the importance of the transcendent (i.e. God as over and above humanity); religions of humanity see human and divine as cooperating partners (e.g. forms of Christianity); and spiritualities of life locate the divine within the human self and nature. Building on these three types, Heelas and Woodhead further differentiate between “life-as religion” and “subjective life spirituality.” “Life-as religion” is characterized by life-as roles, and it emphasizes the normativization of subjectivities. This means, that one’s self-understanding is informed by a source of meaning that transcends human life, and this is translated into one’s everyday social life via institutions such as marriage where the power of the sacred then lies in one’s marital duty, for example. “Subjective life spirituality,” on the other hand, is characterized by the sacralization of unique subjectivities. Accordingly, one’s self-understanding is informed by a source of meaning that can be found within human life. As a result, one’s “self” becomes the primary source of meaning and influence. Rather than being a dutiful wife who disregards her own feelings due to her subjection to her religious context, the individual who emphasizes “subjective life spirituality” listens to those feelings and acts on them by trying to change her life so that she can live more in line with her unique needs and desires.

To begin with, we will give a description of the yoga practice in western European countries. Next, we describe Christian spirituality in the Netherlands. Then, we will present the typology of yoga practitioners, and we will subsequently apply this typology to Christian spirituality. In our conclusion we will show how the typology can clearly outline how participants and practices interact. Lastly, we will suggest how the typology can be applied to other religious and spiritual contexts.

Some Notes on the Yoga Practice

These days, the word “yoga” is resonating throughout the Western world at large. Originally, the word “yoga” describes techniques and methods of meditation and asceticism that are based on classical Indian philosophy. In this sense, “yoga” refers to the “body of spiritual values, attitudes, precepts, and techniques” that have evolved in India during a minimum of five thousand years and that can be considered the building blocks of the ancient Indian civilization.[6] Yoga therefore refers to the varied Indian ways of acquiring self-transcendence; these ways include those that emphasize an atheistic approach, a theistic approach, or a tantric approach.[7] In addition to yoga being a system of techniques, it is also a philosophical system and as such constitutes one of the six main schools of classical Indian philosophy. It is largely based on what has become a source-text of the yoga philosophy: the Yoga-Sutras of Patanjali, which were created between 200 BCE and 200 CE and mark the beginning of what is also considered the “classical” yoga tradition. “Classical” here signifies to the first systematic collection of the yoga teachings. But while the yoga practice is derived from and based in classical Indian thought and spirituality, in the Western context it has been largely detached from its spiritual roots and transcendent aims and is, for the most part, focused around the physical postures and breathing techniques while still, albeit inexplicitly, alluding to the spiritual roots of the practice.[8] This varies from yoga style to yoga style. While on one hand it could be argued that Hatha yoga classes, such as Iyengar yoga, de-emphasize the spiritual dimensions (by not using a lot of “spiritual” terminology in the class) and instead incorporate philosophical aspects (such as the notion that self-transformation may lead to world-transformation), other popular practices, like Kundalini yoga, on the other hand greatly incorporate the spiritual dimension through the language used by the teacher.

Despite the various secular or more spiritual interpretations within modern yoga, one can argue that most modern forms of yoga have four general aspects in common: 1) the existence of systems that regulate one’s behavior in one’s environment; 2) a regular practice of physical and mental exercises; 3) the idea that the physical postures should always be accompanied by an emphasis on mental focus; and 4) the idea that the practitioner works on obtaining a constant “passive” awareness of consciousness-which is different from concentration.[9] Further aspects of the worldview within most modern forms of yoga are certain ethical and moral guidelines that stretch beyond one’s yoga practice into daily life. In particular, two specific ethical aspects of most modern yoga practice are important: 1) “that the practice of yoga should go hand in hand with the performance of voluntaristic ‘good works'” and 2) that self-improvement is at the heart of yoga practice.[10]

Today, yoga in the Western world is typically offered and taught in six kinds of places: 1) in yoga associations, yoga research institutes, and yoga schools; 2) in adult learning centers like the Volkshochschule and others; 3) in sports centers and general health and fitness centers; 4) in other diverse private institutes like companies, schools, and prisons; 5) in parish institutions; and 6) in private homes. In virtually all institutions yoga is only one part of a more general program, and the institution’s existence does not depend on the yoga classes. Only the yoga associations, yoga research institutes, and yoga schools are entirely devoted to yoga theory and practice.[11]

Characteristics of Holistic Christian Spirituality

Christian spirituality is a form of experience-centered religiosity that has become popular in the last two decades in western European countries. In its organization and form it closely resembles other forms of spirituality, which are commonly labeled as alternative. In some cases Christians have explicitly engaged themselves with New Age practices; others, however, have maintained a stricter identification with the Christian tradition.[12] This latter type has mostly become part of an alternative spiritual market, which is characterized by practices and worldviews that come from such diverse sources as Asian religions and neo-paganism. This embedding in the alternative market is typical of Christian spirituality: it is mostly a form of religion that is largely outside institutional spheres of influence, although it cannot be said to be absent from institutional religion. “Institutional” here refers foremost to the Roman Catholic Church because it is from this tradition that most Christian spiritual activities are born, often in spiritual centers that have their origin in one of the religious orders. In the Netherlands the Franciscans, the Jesuits, and the Dominicans have been particularly active in founding spiritual centers, often claiming that the work in these centers is consistent with the tradition of their respective orders. The relationship between Catholic orders and spiritual centers shows how members in the orders began to redefine their traditional praxis as they were influenced by the aggiornamento of the second Vatican Council (1963-1965) and the emerging movements of emancipation and democratization that swept through society as well as the church. Although the emphasis in this modernization of the faith was often political and societal, an interest in contemplative practices was also emerging. International forerunners and initiators of this spiritual modernization among the Catholic orders include the Cistercian monk Thomas Merton and the Jesuit priest Anthony de Mello.

Holistic Christian spirituality is a form of religiosity that is strongly focused on the idea that people are on a spiritual path of growth and development. Practices in Christian spirituality facilitate self-knowledge and spiritual growth. These practices can range from the creation of a spiritual biography to mantra singing to guided meditation. Generally, meditation is the central practice in Christian spiritual centers. It has been noted that this type of Christian spirituality outside the churches shows a big overlap with the kind of services that are offered on the alternative spiritual market in general. The most popular practices on this market are meditation and body-work oriented courses (including yoga), and in Christian spiritual centers we find a remarkably similar package.[13] Considering this overlap we may wonder how the participants can be characterized in terms of motivation. In other words, can we recognize certain types in Christian spirituality as we did with yoga? And if this is the case, what sort of typological variation do the practitioners show?

A Typology of Yoga Practitioners

Before delving further into the typology of yoga practitioners, a few notes are necessary on the theoretical framework within which the yoga practice research was placed, as well as on the methodological tools with which the typology was created. The typology of yoga practitioners was developed within the larger framework of modernity/modernization with a special emphasis on subjectivization theories and how they relate to debates within the sociology of religion. Henrichsen-Schrembs argues that the concept of “going inward,” which is an intrinsic element of the yoga practice, is in line with the increased focus on the subjective self, which is one of the defining characteristics of modernity.[14] In brief, much of the West has been experiencing a major cultural shift through “a turn away from life lived in terms of external or ‘objective’ roles, duties, and obligations, and a turn towards life lived by reference to one’s own subjective experiences (relational as much as individualistic).”[15] In this regard, moving toward religion these days often means being spiritual, a statement which demonstrates the individual’s subjective interest and authority in religious ideas and practices-“freely and from inside, not by compulsion from outside.”[16]

The central question of Henrichsen-Schrembs’ study on the practice of yoga in Germany was why yoga practice had become increasingly popular and what it meant to the practitioner. In order to answer this question, the researcher employed an exploratory, qualitative Grounded Theory (GT) approach. The basic idea behind GT is that theory is to be “discovered from data.”[17] It is therefore an inductive method, and it strongly contrasts with theories that are derived from other theories. Ideally, the researcher works from a tabula rasa perspective, leaving out all other preconceived ideas and theories. This ideal has later been challenged by the argument that it is probably impossible to act without preconceived ideas.[18] Framing her research within a certain theoretical schema, Henrichsen-Schrembs is sympathetic towards these modified approaches towards GT methodology. She conducted problem-centered interviews with twenty-seven yoga students from the following four types of yoga classes: Iyengar yoga, Hatha yoga plus yoga Nidra, Vini yoga, and Kundalini yoga. There are two reasons for this particular choice of yoga classes. First, these classes constitute four popular styles of yoga. This means that they are to be found in most middle to large sized cities in Germany. Second, the classes are primarily physically focused, and while they do not overtly emphasize yoga’s spiritual and philosophical dimension, they often do so implicitly. All four yoga classes provide instruction on how to practice yoga through different schools of thought while only transmitting the broader philosophical and spiritual aspects of yoga to a limited degree. At the same time, within these four classes adherence to a certain religious belief is not important. Within the German context these yoga classes are therefore often considered to be of a secular nature. Thus, from a promotional point of view, these classes appeal to a variety of people and not necessarily only to spiritually oriented people.

Furthermore, the main criterion for the selection of the interviewees was an adequate amount of men and women within the adequate age range-as based on general statistics of yoga practitioners.[19] Within the interviews the focus lay mainly on the role yoga plays within the biography and life course of the interviewee, particularly the initial motivations that prompted the person to start practicing yoga and the reasons that cause the interviewee to continue with yoga practice. This process-oriented interviewing method allowed the interviewee to talk about his/her life in both the past and present, illuminating various aspects of his/her life, such as family and other social relations, upbringing, work and career, health, religious orientation, and how all of the above are related to his/her current yoga practice. In this context it is further necessary to address the question of general correspondence of the collected data. Suffice it to say, the limitations of this sample and of a qualitative study such as Henrichsen-Schrembs undertook are obvious. It is impossible to make any generalizations based on her findings that would extend to the wider population of Germany. However, that is not the goal of such a study. Instead, the researcher’s aim is to illuminate what type of biographies and life courses foster what type and what degree of yoga integration into one’s life. In that sense, the development of a qualitative typology of yoga practitioners in Germany lends itself particularly well to this endeavor. Originally introduced to social scientific research by Max Weber, the methodology of the typology attempts to capture complex social realities and contexts of meaning and to be able to understand and interpret these.[20] As a basic principle, a typology is always the result of the process of grouping aspects of the object of inquiry into different groups or types. Here it is important to fully acknowledge that the types that Henrichsen-Schrembs created within her yoga typology are a combination of various prototypes, put together, in line with Weber, as an ideal type. In reality it is, of course, possible that elements of one type overlap with elements of another type. The methodology of the typology also explains the choice of labels for the four types. Each of them is meant to symbolize, as best as possible in one word, the overarching, essential meaning of the yoga practice for the practitioner.

A first glance at the data shows that there is a wide array of meanings that people attribute to their yoga practice. This ranges from practicing yoga as a form of physical fitness and relaxation to practicing yoga as a form of spirituality. This array comes into clearer focus when one considers the question of the meaning of yoga with regard to the practitioner’s life course, i.e. the presence and absence of negative life-events that are linked to the yoga practice. With this in mind, one can distinguish four broad final applications of and motivations and reasons for the yoga practice: 1) yoga practiced as a tool for (physical and mental) well-being only; 2) yoga practiced in order to foster self-development as well as physical and mental well-being; 3) yoga practiced as a form of self-help/therapy; and 4) yoga practiced as a lifestyle, life philosophy, and form of spirituality.

But why do some people practice yoga only to stay physically fit and “feel good” while others approach it as a source of higher significance and meaning? This is especially interesting when considering that all four typologies of yoga practitioner can be found within the same kind of yoga session. We will take a look at the four types of yoga practitioners, with an emphasis on two aspects: the concept of “going inward” when practicing yoga and the concept of spirituality within the yoga practice.

The Pragmatist

The Pragmatist practices yoga in order to remain physically fit, for relaxation, and for stress reduction. For her, therefore, yoga remains on the level of physical and mental benefits. The life courses of members of this type can be characterized as “smooth,” i.e. without any major negative life events that are related to the yoga practice.

For the Pragmatist, the concept of “going inward” or “finding one’s inner core” refers to taking a “timeout” from her usually busy and hectic daily life, i.e. taking time for herself in order to relax and do something good for her body and mind. The Pragmatist appears to be generally content with her life. She constructively deals with daily hassles, such as stress due to her work, by, for example, practicing yoga and “going inward,” which helps her to relax the tension she experiences. In the case of Jessica, going inward means “finding my inner core,” which serves as a way of improving her quality of life. Therefore, for Jessica, her Tuesday morning yoga class is like “a little island where she can find herself and gain strength” for her daily life. “Going inward” takes place during the yoga session, and when this goal has been achieved she is no longer concerned with it until the next yoga class. It is a specific experience during a specific time only. As regards the notion of spirituality, for members of this group religion did not play an influential role in their lives when growing up nor does it play an important part in their lives now. As such, the same applies to the spiritual elements within the yoga practice-they are not important for the Pragmatist.

The Explorer

Someone from this type has described yoga in this way: “What I was especially attracted by with regards to yoga was the meditative aspect. The inner immersion. That’s what I was aiming at.” The Explorer practices yoga not only for physical and mental wellness but also in order to foster self-development and self-exploration. Characteristic of the Explorer is a life course that is primarily “stable”-there is no mention of major negative life events that are still significantly affecting her today and that would be related to her yoga practice.

A major significance of the practice for the explorer lies in the possibility of further developing and exploring herself through yoga. This is achieved by “going inward,” i.e. by paying attention to what is going on inside one’s body and mind. “Going inward” refers not only to relaxation but also to wanting to learn more about one’s inner self in order to make changes. Self-development and self-exploration are often applied as a tool for better managing one’s daily life. Susan, for example, points out that while she grew up very achievement oriented, yoga has enabled her to slow down and adopt a different attitude towards life, i.e. one in which achievement is not the prime motivation and one that allows her to listen to her internal self.

While the Explorer engages with self-development and self-exploration she does this only insofar as it helps her to better manage specific concrete difficult situations; through yoga she tries to let go of old behavior patterns that proved to be useless and to apply new constructive behaviors. In this sense one could say that the Explorer adopts those bits and pieces of the greater philosophical framework of yoga that work well for her without embracing yoga as a life philosophy in its entirety. The yoga practice is a means to an end: to self-development, self-discovery, and the improvement of one’s quality of life.

Regarding the importance of spirituality, the Explorer often refers to yoga as something spiritual or as a life philosophy. However, common to this category is a certain skeptical attitude towards doctrinal or dogmatic impositions of any kind. For example, Anna differentiates yoga from other sports by referring to it as a life philosophy. It is, however, of utmost importance to her that her yoga teacher does not “push” this onto her.

The Self-Helper

The Self-Helper practices yoga in a therapeutic way. Characteristic of this type is that her yoga practice is directly related to the experience of negative life events. Furthermore, in addition to practicing yoga, she might have pursued other similar activities, like Tai Chi or Bioenergy, as well as various kinds of therapy.

The wish to better cope with one’s personal problems is accompanied by the wish to learn more about oneself through the kind of introspection that the yoga practice can offer. As such, by “going inward” the Self-Helper hopes to foster her self-awareness in order to recognize certain patterns and then learn how to effectively change or let go of them. For Bettina, “going inward” and finding her “inner unison” means recognizing her needs and desires as well as paying attention to what “is” inside her, i.e. to the potentials inside herself that she has not yet realized. Characteristic of the Self-Helper is reflection upon her life with regards to the yoga practice by referring to her childhood as well as to specific profound, difficult life events. Rather than looking forward, into the future, her self-perception is informed by her past; she makes sense of her current life situation and her “issues” by relating them to events in the past. “Going inward” and improving one’s self-awareness therefore means working through psychological issues and patterns in order to move one’s life from a difficult situation into a different direction. Yoga is applied in a therapeutic way.

Another characteristic of this type is a yearning for spirituality as a way of making sense of one’s life. While the Self-Helper does not necessarily adopt the yoga spirituality as her belief system, she sympathizes with the spiritual dimensions of yoga and integrates parts of them into her life. Angelika, for example, is a devout Protestant who is actively engaged in her church community. In contrast to what she describes as the traditional “punishing” God of Christianity, she believes in a God who is benevolent and who has created a “plan” for her. While she feels a little bit “uncomfortable” and “foggy” with regards to certain spiritual yogic ideas, such as reincarnation, she nevertheless sees some parallels between participating in a church service and practicing Kundalini yoga, especially the meditative parts of it. As such, she feels a connection to the divine when sitting in silence during the yoga practice. Yoga thus supports her in her own religious belief, as it is another form of experiencing the spiritual. The therapeutic significance of “going inward” via yoga for the Self-Helper, then, also lies in the possibility of establishing a connection with and experiencing the divine. Through this she learns to accept herself and to be “gentle” with herself.

The Mystic

The Mystic, as the name implies, has more or less completely subscribed to yoga as a worldview or as a form of spirituality. As such, she integrates the yoga philosophy and its spiritual dimension into her daily life via daily physical practice and meditation, eating and drinking according to yogic beliefs, and more or less completely adopting yogic ethical standards for her life (to the extent that this is possible in modern, Western society). The Mystic often becomes a yoga teacher herself. Her practice is often directly related to her experience of one or more negative life events from which yoga has helped her to heal. Finally, for the Mystic the yoga practice is always linked to a spiritual expression or to her idea of the divine.

A central tenet of the concept of spirituality within this type is the idea of “the divine” as part of the self and of the consequent ability to experience the divine through the self, particularly through the body. In Andrea’s words: “It is not about a personified idea of God, but it is about the creative force or the creative force within each of us. What is being taught in yoga is that God and I are one. There is no separation, so to speak. There is simply no separation.” Or, as Miriam says: “For me God is not some great strange power, sitting up there somewhere, like a bureaucrat, writing down ‘ah, Miriam got herself into trouble again,’ but for me God is also a part of me. That means God is also inside me, and he is outside me, and he is inside of every human.”

Therefore, in addition to its therapeutic significance as a tool of self discovery, “going inward” and “finding one’s inner core” when practicing yoga means establishing a connection to something spiritual or to “the divine.” In fact, it is only through self-discovery, through looking deeply inside oneself, that it is possible to realize that one already carries “the divine” inside oneself. As Miriam puts it: “Through the concentration within yoga on what it is that I am doing, I am getting in touch with it. I am getting in touch with the God within me, or we can say, I’m getting in touch with the spiritual part of myself through this concentration.” The Mystic could be regarded as a culmination of all the prior types, in the sense of a spiritual virtuoso; there is a culmination with regards to the intensity of life as it is experienced as well as with regards to the experience of spirituality.

To conclude, the typology clarifies that there are different types of yoga practitioners showing different motivations and interests that lead people to practice yoga. It indicates that yoga lends itself to different forms of “going inward,” some spiritual and some not. Specifically, the life paths of the practitioners are largely responsible for the ways in which yoga is being practiced, to what degree it is integrated into the individual’s life course, and the role its philosophical and spiritual dimension plays for the practitioner.

Table 1, Four Types of Relationships between the Integration of One’s Yoga Practice and One’s Life Course

Summing up, one can see that the smoother and “easier” the life course of the individual is, the less she is interested in the use of yoga as a form of (psycho-) therapy and in its philosophical and spiritual dimension and the more the physical and mental exercise and relaxation aspects are relevant as well as the interest in self-exploration. Conversely, the more “difficult” and challenging the life course of the practitioner is, i.e. interspersed with negative and/or critical life events and transitions, the more likelihood there is of yoga being a coping strategy to better deal with these “issues” and the more the philosophical and spiritual dimensions are emphasized and integrated into the person’s life. The motives and reasons to practice yoga thus differ for each type. While for the Pragmatist the motivations and reasons to practice yoga remain always on the level of physical and mental benefits, for the other three types the motivations to practice yoga may gradually change to increasingly emphasize self-reflection and changes in one’s life and one’s view of life.

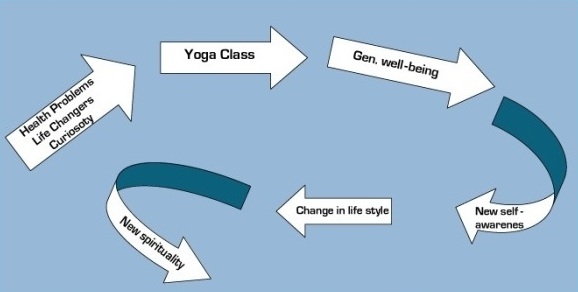

However, the four types should not be seen as exclusive but as potential stages in a practitioner’s spiritual career, as the diagram below illustrates:

This figure illustrates that there seems to be a change in one’s motivations and reasons while one practices yoga: yoga students, who signed up for the yoga class due to physical health problems often realize that yoga also positively influences their mental and psychological well-being. Then a shift seems to take place where the latter becomes the more important reason to continue to practice yoga. This, in turn, has the possibility to cause the individual to make changes in her lifestyle, e.g. pragmatic changes such as taking more time for herself or even adopting a whole new spiritual awareness and totally identifying with the yoga philosophy.

A person might start her yoga practice due to back pains, for example, and she might discover that, in addition to the back pain diminishing, she feels more relaxed in general and would like to learn more about meditation techniques. Or, while she started to practice yoga because of physical issues she now develops an interest in some of the values, such as mindfulness with oneself and others, which the yoga philosophy traditionally emphasizes and which are often touched on in the yoga session. Meditation can help with a wide array of health and well-being concerns, such as pain, anxiety, and depression. Utilizing the traditional philosophies of yoga can help you to make the most out of each session. This might lead to the wish to study yoga on a deeper level, to practice it at home, and in some cases to embark on yoga teacher training.[21]

As figure 2 points out, it is reasonable to assume that in view of the changes as a result of the yoga practice the individual’s negative life-events also gain a different meaning for the individual (e.g. they can be regarded as a positive factor in facilitating overall change). Furthermore, it is reasonable to assume that a person for whom religion/spirituality has always been an important part of life is more likely to take up yoga as a spiritual path than a person for whom religion/spirituality is generally unimportant. In the former case, the experience of negative life events is not a prerequisite for the individual to become a Mystic. At the same time, it is fair to assume that not all people who experience negative life events use yoga as a coping strategy or find existential meaning in the yoga spirituality. Again, the limitations of the sample are apparent, and such claims would have to be confirmed through large-scale research. In the next part we will test the typology’s value in the context of another part of the alternative spiritual market: holistic Christian spirituality.

Types in Holistic Christian Spirituality[22]

[Meditation], that’s something for me. You know, I like a bit of reflection now and then, for myself. Just when you are alone, thinking about your life, and it may even be in-between some things you are doing, as long as you give it attention. I am not a philosophically inclined person, but I do feel like paying attention to things: am I doing it right, could I improve it, what is happening around me, um, how do I deal with that. That kind of thing, that you are paying attention to that. Not just something happening by coincidence and then like, OK, that’s what you do.

These were some of the things that Marry, a woman in her late sixties, had to say about her experiences with meditation practice. Marry described herself as an agnostic who had not been to a church service since she was thirty years old. The memory of churchgoing was already so distant that she did not even want to label herself an ex-Catholic. And yet, the reason for the interview was the fact that this woman was a regular participant of a meditation group working in a so-called Ignatian practice; the group was part of a Christian spiritual center in Amsterdam. Several things were striking in this respect. Marry did not seem bothered by the Catholic identity of the practice in which she participated. Moreover, she had found her own way of using and interpreting meditation, relatively separate from the manner in which the meditation was structured. Marry had integrated meditation in her life in much the same way that she had taken up nature and city walking in her spare time: as ways of reflection and relaxation.

Seen from the typological perspective, Marry can be classified as a Pragmatist. Her motivations are pragmatic, with an emphasis on relaxation and having some time for herself. She sees other leisure time activities in the same vein as meditation. The religious overtones of meditation are viewed as redundant and are ignored as much as possible, although they are respected as meaningful to other practitioners. Interestingly, the Pragmatist is really a minority within the context of Christian spirituality. The agnostic pragmatism of this type is quite rare. Most practitioners will have some affinity with religion, in particular with Christian mysticism or other religious traditions such as Buddhism and Hinduism. This suggests that the other types will have a stronger presence in Christian spiritual centers.

Visitors of Christian Spiritual Centers

A representative sample taken from a population of visitors of one season of activities at a spiritual center showed that participants are mostly women above the age of fifty, slightly more educated, and often with a Catholic background. About half of this group still regard themselves as Catholics; the other half see themselves as unaffiliated but often mention being brought up Catholic. A much smaller group comes from other religious backgrounds.[23] This corroborates with the interview data from Christian spiritual centers in the Netherlands, in which twenty-two people involved in Christian holistic spirituality were interviewed.[24] Practitioners of Christian spirituality generally have a strong interest in religion but clearly reflect the trend of the movement from “religion” to “spirituality.”[25] In this case this means that people are convinced of their right to find their own meaning through religion and that they are free to choose their own sources of inspiration for this quest. For many, church involvement is complemented by participation in spirituality. For others, practicing spirituality is a way to heal from the hurt that they feel the church and “official” religion have inflicted on them. This group experiences spiritual practice as a way out of what they see as authoritarian religious structures.

In general we can conclude that Christian spirituality fulfils an emancipatory role for this group when we take into account that most practitioners have a first-hand experience of being brought up in a Catholic subculture at a time when religious authority self-evidently coincided with the institution. Similar to many unchurched seekers of meaning, the Christian spirituality practitioners have moved their search beyond the institution and its monitoring and sanctioning authority. They have thereby appropriated a more autonomous way of making religion meaningful in a personal way. Thus, if we make a division according to the typology suggested in this article, we have to keep in mind that practitioners of Christian spirituality all share the characteristics of an emancipated subject who will emphasize personal experience and autonomy. Having said this, how can Christian spiritual practitioners be categorized in the typology? And what does this say about their motivation to practice spirituality?

The Explorer

The quest is one of the strongest metaphors used in Christian spirituality. The idea of being on a quest is central in the vocabulary offered to participants. It is also the kind of idiom that people will start to appropriate when they (learn to) talk about their experiences. Meditation practices often deal with themes of exploration; in particular guided meditations provide sketches or drawings of landscapes or buildings in which participants move. We could say that Christian spirituality fosters an explorative modus of spiritual practice; it sees personal exploration as normal and normative to building a healthy self.[26] Interestingly, the narrative content of the practice is not precisely articulated. In fact practitioners have a lot of room for forming their own meaningful experiences, for creating a “hermeneutic space.”[27] This suggests that the Explorer can be found among practitioners of Christian spirituality. For the participants in Christian spirituality that were interviewed, inner exploration is certainly a goal. Described as a search for inspiration or a process of spiritual growth, practitioners attest to the idea that spirituality is a world to be discovered. Striking examples include a woman who, through Buddhism and neo-shamanism, became curious about Catholic mysticism-“my own background,” as she said; or a man from an atheist Jewish background who combines an interest in Rudolf Otto’s Das Heilige with a fascination for St. Bernadette of Lourdes and an occasional visit to the Liberal synagogue.

The Self-Helper

As we indicated earlier, for most practitioners, exploration is a process of religious seeking through which people try to complement or transcend their Catholic religiosity. However, spiritual exploration may lead to experiences of loss or other difficulties. For example, Liesbeth talks about the peace she feels when the meditation group starts with a moment of silence:

Sometimes, I think, yes, this is it . . . that you really, yeah, that you become very quiet and really come to yourself. That happens, sometimes, not often. [Interviewer: Can you explain what happens when you come to yourself?] Yes, it’s that I am brought to tears, and I think, what is happening? I can’t even explain it; it just happens. So then I feel sad. A lot of emotions come to the surface. Closer to my feeling. That I get out of my head. That’s what I notice. And I find this very quieting.

Liesbeth is a retired single woman from a “strict” Catholic background. In her late adolescence she left the Catholic church of her youth, and she says she is allergic to everything that smells like Catholic tradition. A continuing interest in existential questions brought her to spirituality, including Christian spirituality. For the past few years, Liesbeth has suffered from an eye disease that has deteriorated her sight to the point that she is almost blind. Although she finds it difficult to understand what happens or to put it into words, participating in a meditation group clearly is a moment of peace in which she can be open to her sadness about her condition. For her, spirituality becomes more and more a way to be at peace with herself and her affliction.

Although it is obvious that not all participants in Christian spirituality have the same experiences as Liesbeth, it is striking to see how often an explorative mode borders on an attitude in which spirituality is seen as a way to come to terms with life and to reach personal equilibrium. In terms of the typology, in Christian spirituality the Explorer and the Self-Helper live very close to each other, sometimes sharing the same house. Christian spirituality does not have a clear theological narrative that it conveys to participants; yet, paradoxically perhaps, its approach constructs the spiritual in terms of healing through finding oneself, making therapy a logical consequence of a personal quest.

The Mystic

As with contemporary yoga, the Mystic is clearly present in the context of holistic Christian spirituality. The first examples that come to mind in this regard are the various religious specialists working as volunteers or professionals in Christian spiritual centers. To this group of people, spirituality really is an indispensable quality of who they are, something that is fully integrated into their lives. As the director of a Christian spiritual center says about her daily spiritual practice: “Every morning [the team of the center] starts in the chapel. I find that important. To connect to the Light that carries each of us. That we become aware of that.” But among practitioners there are also people for whom practicing spirituality is more than a part-time activity. For example, Beatrijs, a forty-ish Protestant woman who started her own spiritual consultancy after intense participation in a Franciscan spiritual center, calls her discovery of spirituality “recognizing something that was already there.” Spirituality was simply a way of naming it, and the “recognition” moved her to participate in spiritual courses, studying theology and developing her own theoretical and practical approach. Her experience testifies to the undoubted presence of a spiritual dimension in her life, thereby showing a conviction that we would easily call “religious.” Although it seems that the adoption of Christian spirituality as a worldview primarily occurs with religious specialists in that setting, there are other practitioners who have fully integrated spirituality into their lives.

If we look at the typology, it appears that the largest category in Christian spirituality is the Self-Helper. However, we should be aware that this is partly due to the fact that “therapy” is seen as a broad term; moreover, in spirituality the boundaries between exploration and therapy are fluid.

Conclusion

We have shown that the typology that was used to categorize yoga practitioners in Germany can be applied to another form of alternative spirituality: holistic Christian spirituality in the Netherlands. As with yoga, this type of Christian spirituality is able to attract various categories of people with different motivations. The different types in yoga indeed have their counterparts in Christian spirituality. For example, looking from the angle of the typology, we can spot (mutatis mutandis) a correlation between certain degrees of involvement and spiritual intensification as they pertain to both yoga and Christian spirituality. In yoga it seems that one becomes more spiritual (and religious, as is the case with the Self-Helper) once one acknowledges the therapeutic dimension of the practice. In Christian spirituality we see a similar process as people gradually take up spirituality as an important dimension or orientation in their life.

However, the application of the typology outside its original context makes clear that there are some differences between the two forms of spirituality, too. A first important difference is that yoga is offered in various organizational settings, ranging from gyms to specific yoga centers, whereas Christian spirituality is most often restricted to its own circuit of spiritual organizations. Access to yoga is, therefore, easier than access to Christian spirituality. We thus conclude that both yoga and Christian spirituality already select practitioners through the way in which activities are organized. Second, in yoga it seems that practitioners can more easily integrate the practice in a pragmatic way, leaving aside spiritual connotations, while this is less easy to accomplish in Christian spirituality. In the latter setting people are often confronted with the idea of spirituality as a practical path for personal change-even though, as we said earlier, it does not communicate a specific religious ideology. This, again, is a consequence of the way in which both forms organize their practice in terms of message and target group.

The four types-“The Pragmatist,” “The Explorer,” “The Self-Helper,” and “The Mystic”-illustrate four different applications of yoga into an individual’s life. They illustrate how the same kind of yoga practice can carry such diverse meanings and significance for a person in modern Western society. This should not surprise us if we understand contemporary attitudes towards religion as highly subjectivized, as we have in this paper. What the typology makes clear is that people can relate to religion and spirituality in different ways in contemporary society through different degrees of involvement. Although the typology was developed to analyze the motivations of yoga practitioners in Germany, we have shown that it can be applied to other forms of alternative spirituality in another Western European country as well. This raises interesting questions about the cultural adaptation of spirituality as well as the possible cultural receptiveness for spirituality in modernity. A further merit of the typology is its ability to clarify the specific variation of types within different forms of spirituality. As such it can be used as an interpretive tool to compare different contexts of spiritual and religious practice.

[1] As regards the yoga practice, the largest body of scholarly work on yoga has been written from within the yoga tradition and is based on the original texts and thus rather theoretical in nature. Only in recent years has there been a growing body of academic research and literature on the actual experience of yoga for the “modern” practitioner. See: Joseph S. Alter, Yoga in Modern India: The Body Between Science and Philosophy (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004); Véronique Altglas, “Indian Gurus and the Quest for Self-Perfection among the Educated Middle Classes,” in Salvation Goods and Religious Markets: Theoretical Concepts and Applications, ed. J. Stolz (Bern: Peter Lang, 2008), 211-234; Suzanne Hasselle-Newcombe, “‘Spirituality’ and ‘Mystical Religion’ in Contemporary Society: A Case Study of British Practitioners of the Iyengar Method of Yoga,” Journal of Contemporary Religion 20 (2005): 305-322; Elisabeth De Michelis, A History of Modern Yoga: Patanjali and Western Esotericism (Oxford: Blackwell, 2005); Benjamin Smith, “Body, Mind and Spirit? Towards an Analysis of the Practice of Yoga,” Body & Society 13 (2007): 25-46; Sarah Strauss, Positioning Yoga: Balancing Acts across Cultures (Oxford: Berg, 2005).

[2] Paul Heelas, The New Age Movement: The Celebration of the Self and the Sacralization of Modernity (Oxford: Blackwell, 1996).

[3] Sabine Henrichsen-Schrembs, “Pathways to Yoga-Yoga Pathways: Modern Life Courses and the Search for Meaning in Germany.” PhD diss., Graduate School of Social Sciences, University of Bremen, 2008.

[4] In the original work, the different types are called the “Exerciser,” “Explorer,” “Self-Helper,” and “Yogi,” but for the purpose of this article the authors changed two of the names.

[5] Paul Heelas and Linda Woodhead, The Spiritual Revolution: Why Religion is Giving Way to Spirituality (Malden: Blackwell Publishing, 2005).

[6] Georg Feuerstein, The Yoga Tradition: Its History, Literature, Philosophy, and Practice (Prescott, Arizona: Hohm Press, 1998).

[7] Christian Fuchs, “Die Geschichte des Yoga,” in Der Weg des Yoga: Handbuch für Übende und Lehrende, eds. Berufsverband Deutscher Yogalehrer (Petersburg: Verlag Via Nova, 1994), 3-15.

[8] De Michelis, A History of Yoga; K. Liberman, “Yoga Tourism in India” (unpublished manuscript, n.d).

[9] D. Ebert, Physiologische Aspekte des Yoga und der Meditation, (Stuttgart: Fischer, 1986).

[10] De Michelis points out that these two characteristics are unique to modern forms of yoga as they are not addressed in this sense in classical yoga. It is these two aspects, among others, that give yoga its pragmatic and humanistic nature. Moreover, the self-improvement theme, De Michelis argues, is interpreted by Iyengar yoga in a rather eclectic and individualistic way, and this theme is linked to the language of Jungian and transpersonal psychology (De Michelis, A History of Modern Yoga, 219).

[11] Christian Fuchs, Yoga in Deutschland: Rezeption, Organisation, Typologie (Stuttgart: Verlag W. Kohlhammer, 1990).

[12] Darren Kemp, “The Christaquarians? A Sociology of Christians in the New Age” in The Encyclopedic Sourcebook of New Age Religions, ed. J.R. Lewis (Amherst: Prometheus, 2004), 323-335.

[13] Stef Aupers and Anneke van Otterloo, New Age: een godsdiensthistorische en sociologische studie (Kampen: Kok, 2000); Peter Versteeg, “Spirituality on the Margin of the Church: Christian Spiritual Centres in The Netherlands,” in A Sociology of Spirituality, eds. Kieran Flanagan & Peter C. Jupp (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2007), 101-114.

[14] Robert N. Bellah, et al, Habits of the Heart: Individualism and Commitment in American Life (Berkeley & Los Angeles: The University of California Press, 1985); Eric Hobsbawn, Age of Extremes: The Short Twentieth Century (London: Abacus, 1995); Ronald Inglehart, The Silent Revolution: Changing Values and Political Styles among Western Publics (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1977); Ronald Inglehart, Culture Shift in Advanced Industrial Society (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1990); Charles Taylor, Sources of the Self: The Making of Modern Identity (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989).

[15] Heelas and Woodhead, The Spiritual Revolution, 2.

[16] Charles Taylor, A Secular Age (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2007), 535.

[17] B. Glaser and A. Strauss, The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research (Chicago: Aldine, 1967).

[18] Anselm Strauss and Juliet Corbin, Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques (London: Sage Publications, 1990).

[19] Fuchs, Yoga in Deutschland; Strauss, Positioning Yoga.

[20] Max Weber, “Objectivity in Social Science and Social Policy,” in The Methodology of the Social Sciences, eds. E.A. Shills & H.A. Finch (New York: Free Press, 1904/1949); Udo Kelle & Susann Kluge, Vom Einzelfall zum Typus: Fallvergleich und Fallkonstrastierung in der qualitativen Sozialforschung (Opladen: Leske und Budrich, 1999).

[21] When the latter is the case, the wish to become a yoga teacher is motivated by three aspects: first, there is the idea of passing on the yoga practice to the public because one deems it an important endeavor; second, the yoga teacher training provides the possibility for a career change; third, there is the possibility to simply engage in a supervised in-depth study of yoga and its traditional philosophical and spiritual framework out of personal interest.

[22] Data are derived from fieldwork research carried out between 2001 and 2003 in various Christian spiritual centers in the Netherlands. This research was part of the “Between Secularisation and Sacralisation” programme of VU University Amsterdam. See André Droogers, “Beyond Secularisation versus Sacralisation: Lessons from a Study of the Dutch Case,” in A Sociology of Spirituality, eds. Kieran Flanagan & Peter C. Jupp (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2007), 81-99.

[23] Data from an internal unpublished report made for the Franciscan spiritual center La Verna in Amsterdam by one of the two authors. Interestingly, about three-fourths of the respondents identified themselves as “having a worldview.” The data on social characteristics is in line with findings from the study of Heelas and Woodhead on the holistic milieu in Kendal, UK. In their research the authors show that subjectivization has taken place within many parts of the congregational domain and that those active in the latter have also become active in the holistic mileu with “forty-five percent of all those active in the holistic milieu [being] women aged between 40 and 60” (Heelas and Woodhead, The Spiritual Revolution, 107).

[24] Peter Versteeg, “Meditation and Subjective Signification: Meditation as a Ritual Form within New Christian Spirituality,” Worship 80 (2006): 121-39.

[25] Heelas and Woodhead, The Spiritual Revolution, 6-7.

[26] The view on human beings in Christian spirituality is very positive, founded on a belief in the inner potential that everybody possesses and that can be disclosed. Suffering and hardship are completely taken into account in this kind of spirituality. In this acceptance of oneself, personal flaws and the imperfection of life are understood as crucial aspects of healing.

[27] Versteeg, “Meditation and Subjective Signification,” 137.