Download PDF: Editorial Issue 4

Introduction

The authors and creators of the pieces in this issue address a wide variety of health-related topics that sit at the intersections of religion, health, and healing work. These include HIV/AIDS, disability, women’s reproductive health, cancer, health promotion, mental illness, and death and dying. Additionally, they offer a glimpse of the ways religion, health, and healing are understood by researchers, practitioners, and observers of everyday life. Contributors examine these intersections from disciplinary and tradition-specific lenses, and they push us beyond disciplinary and traditional boundaries, examining the promises and limits of both types of research and practice. In short, these authors and creators offer us a rare picture of what Linda Barnes names as the “new geography” of work in religion and health. To borrow from Barnes’s metaphor, this issue examines the geography of this emergent field, beginning with Barnes’s own excellent state of the field essay. This essay explores the historical emergence of the study of religion and health, delves into the ways this field has emerged within and between disciplinary boundaries (religious studies, medical anthropology, psychology to name a few), and elaborates upon the ways these intersections have been examined within and beyond religious traditions themselves. As Barnes notes, the emergence of this field of study points to a crucial issue that the authors in this issue address as a matter of course: the fact that “matters of healing often lie just beneath the surface of the religious. Lift the cover and there they are.”

This issue provides such an unveiling of the health and healing matters that affect the research and practice of religion. As we have examined the ways that the authors and creators featured here do this unveiling work, we identified several key themes that emerged as the issue took shape. They include:

- Language and Translation – Authors and creators featured in this issue examine the ways that navigating the discursive and practical arenas of religion and health involves some translation work. Key questions among these pieces include: How do the languages of religion and health speak to and with one another? How can we better facilitate a dialogue between these disparate languages? How can translation between these discursive and practical arenas happen in an ethical way? What spaces (physical or imagined) need to be created in order for this translation work to happen?

- Directionality – Several pieces in the issue highlight the need for increased attention to the ways research and practice in religion and health is shaped. In other words, they address the question of who and what drive research and practice agendas in the field of religion and health. Key questions these authors and creators ask include: Who has the power to name key issues in research and practice in religion and health? What are the epistemological assumptions guiding research and evaluation expectations in this field? How do these assumptions affect practice and care? How can community-based methods of research shift the paradigm of research and empower communities to name and address key concerns and practices?

- Religion’s influence on health and health as religion – The question of how religious practices influence health and healing, and conversely, how health practices influence and shape religious identities and traditions, was central to several authors and creators in this issue. Key questions they address include: How do religious and biomedical practices intersect in the treatment of illness and the attainment of health and wholeness? How do religious practices, traditions, and beliefs shape the ways that healing itself is understood and defined? How does healing shape the ways religious identity develops and is understood? What are the boundaries between religious and healing practices?

Below we elaborate upon these themes, drawing on the work featured in this issue. Although we have highlighted the main themes we identified in the crafting of the issue, it is our hope that this issue will stimulate further conversation and research in this interdisciplinary and emergent field of religion and health

Language and Translation

The issue of how to negotiate different cultural worldviews of health and faith emerges throughout this issue. Interestingly, while each piece offers a different response to the divide, many of our authors frame this question of religion and health as based in different “languages.” For these authors, language’s relationship to worldview is a vital dimension to understanding, interpreting, and realizing health and wellness in a community. To effectively adjudicate between the discourses of faith and medicine, some translation is necessary. However, different authors present different means for this translation ranging from creating new conceptual frameworks, to pedagogical play, to the creation of particular spaces for interaction between these disparate discourses.

In his essay “The Language that Difference Makes: Translating Religion and Health,” James Cochrane articulates the problematic categorization of health and religion as two disparate entities. This dualistic conceptualization of the world emerges as a particularly Western construction, one that is not “translatable” for those working in other cultural contexts. In the case of the Lesotho people, for example, the idea of separating religion and health proves to be “impossible” in the Sosotho language. Conceptually and linguistically, there is no distinction between religion and health. In response, Cochran proposes that Western language must find a way to be more hospitable to unfamiliar cultural landscapes. In other words, the attempt to translate concepts like religion and health challenges the very concepts we hold. Linguistic hospitality entails a certain invention of language, a creative act that Cochrane adopts by proposing the term “healthworld” as a way to bridge the traditional Western concepts with a more integrated way of understanding health. Thus, a translation of Sosotho language and thought might enhance and improve Western healthcare’s ability to communicate and learn from other worldviews.

The issue of translating one concept to another is also addressed in another context in Brendan Ozawa-de-Silva and Brooke Dodson-Lavelle’s piece, “An Education of Heart and Mind: Practical and Theoretical Issues in Teaching Cognitive-Based Compassion Training to Children.” Dodson-Lavelle and Ozawa-de-Silva seek to translate compassion meditation derived from the Tibetan Buddhist tradition of lo-jong, or “mind training.” Their students include a classroom of six- and seven-year-olds at a private school in Atlanta and a foster care group of preadolescents. These authors draw on a conception of the secular as a middle space between the religiously derived paradigm and biomedical paradigm in order to benefit the health of a community and individuals.

A third model for how to bridge the cultures between health and faith is seen in a physical space designed specifically for a Memphis hospital, the Congregational Health Network for Methodist Healthcare. In the video interview between Gary Gunderson and Bobby Baker, the viewer sees the actual physical environment and space that is vital to making the communication between pastors, local health workers, and the hospital possible. The center is grounded in the belief that patient care and health care research should grow from the “blended intelligences of faith and the health services.” The busy, and a bit chaotic, dimensions of a large community institution come to life as one listens to the conversation of these two formidable leaders in the Memphis community. Through this particular medium of film, the contingent nature of negotiating these difficult paradigms of health and faith are localized in a particular place.

Two pieces in this issue address the issue of language by looking to narrative. For Mary Helen Harris, Ann Miliken Pedersen, and Ellie Schellinger, teaching through narrative enables their students to reflect on issues of reproductive ethics in complex and rich ways. In their essay, the authors reflect on the difficulty of grappling with questions of abortion, reproduction, and cloning in light of differing claims about “human life and death, health and wellness” made by competing systems of meaning. The authors suggest that bringing these competing claims together through narratives rooted in human experience acknowledges this dissonance while moving forward a constructive conversation around important human life issues. One pedagogical strategy they recommend is to have students “try on” other’s narratives through a kind of “deep play.”

Finally, Margaret Aymer and Guy Pujol bring together New Testament scholarship and pastoral care to address the ways healing miracle stories in the Christian tradition relate to the AIDS/HIV epidemic. Written as a dialogue between two scholars, the authors discuss the pedagogical strategies they employ to help students responsibly utilize sacred texts in relationship to contemporary diseases and models of healing. Like the dissonant narratives conversation, these authors also speak about the ways in which dissonance can be “deadly” for those who choose one narrative over another in order to make sense of their illness. For example, some HIV-infected Christians may elect to forego medical interventions, believing that their faith requires them to eschew any human efforts in favor of more a direct miraculous work of God. If they pray hard enough, they will be well. The gap between medical and religious discourse can in some cases prove lethal. In response, these authors recommend creating a more “integrative” course that intentionally brings biblical exegesis and pastoral care together.

In all of these pieces, the question of bridging the gap between two languages is the key to bringing about a more whole and just community. Religious beliefs and biomedical paradigms are both acknowledged and encouraged to be more fully in conversation through a variety of linguistic and pedagogical strategies.

Directionality

Another key element of research in religion and health that emerges in the contributions of this issue is related to the issue of directionality. In other words, our authors point us toward an examination of who, or perhaps more importantly, what drives the research agenda. This question is particularly important, John Blevins and Elizabeth Toler note, in interdisciplinary work aimed to enhance and increase the positive health outcomes of an individual or community population. As they write, “the question of epistemology—what counts as knowledge in interdisciplinary research—is not merely a theoretical question. It also impacts practice.” Their piece points to the tension between religiously-oriented health practices (in their case, coming from the field of pastoral counseling) and health-oriented research that draws on religious practice (for example, evidence-based medicine). While both fields aim to improve health, the ways health is defined, measured, and enacted can differ dramatically. As the emerging field of religion and health continues to define itself, these questions of direction will become increasingly important, not only because they impact research but, most significantly, because they have a concrete effect on the health and wellbeing of others.

Authors in this issue wrestle with these intersections in different ways and from unique disciplinary and tradition-specific backgrounds. For some, the question of measurement and effectiveness is defined by the parameters of the field of research related to health education and behavior. Shirley Banks, a health educator at Emory University, describes the individual health behavior effects of meditation and her own experiences teaching meditation as a health educator. Like Banks, epidemiologist Lori Carter-Edwards argues for increased attention to religious practices, beliefs, and behaviors among health practitioners. In order to increase positive health outcomes for African-American cancer patients, physicians, she argues, should be educated to listen to and learn from their patients’ spiritual beliefs. Although the focus of this research is on individual and communal health behaviors and outcomes, these authors remind their colleagues in the health-related fields to widen the scope of their research and practice to include attention to previously ignored religious practices (meditation, spiritual beliefs, religious coping) in order to improve mental and physical health.

Writing from the field of Christian theological ethics, Matthew Bersagel-Braley tackles the question of directionality in his piece “Checking Vitals: The Theological (Im)Pulse of Christian Leadership in Global Health.” Bersagel-Braley examines the potential constructive contributions of religious institutions, organizations, and traditions to health work. He looks to a historical example, the Christian Medical Commission, to demonstrate “how persons and institutions committed to ongoing theological reflection can help facilitate transformations in the fundamental commitments of global health institutions.” As Bersagel-Braley argues, the constructive voice of religious traditions can change the shape of global health practice, if they are given a voice with which to do so.

This issue of listening to those whose voices often go unheard in health-related research and practice is taken up by several authors in this issue, notably Mary Ann Burris, whose work is highlighted in our Features section, and Forrest Toms, Cheryl LeMay Lloyd, Lori Carter-Edwards, and Calvin Ellison in their article “Improving Health and Healthcare Advocacy through Engagement: A Faith-Based Community View.” In both of these pieces, a community-based model of research in religion and health is advocated. This leads to a reconceptualization of the question of not only who drives research on religion and health (and who is allowed to contribute constructively) but also how religion, health, and healing are even defined and understood within communities.

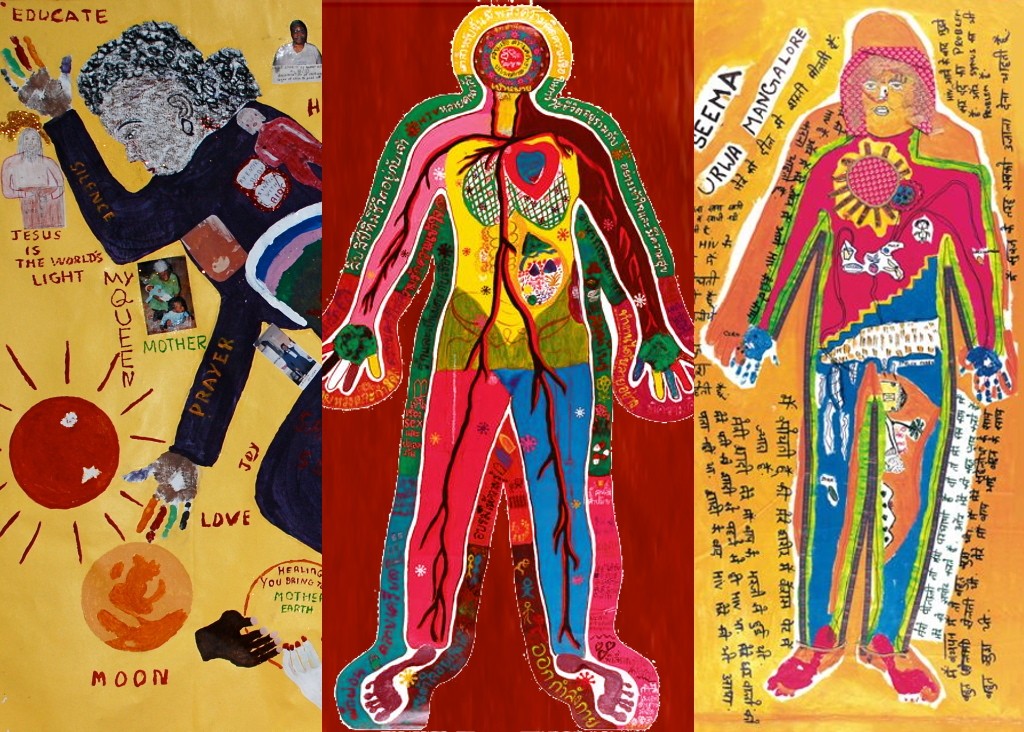

For Burris and her organization, Trust for Indigenous Culture and Health (TICAH), “the first step in doing good work is to listen. When we listen, culture pours in. Values are shared. Health is defined in ways that make sense, that spring from the details of daily life.” By listening first, TICAH hears the contributions of the community and allows them to shape the direction of the research and practice paradigm. As Burris contends, this not only generates community investment in a program, it also leads to innovative and effective strategies to address the most pressing health needs of a community. Toms, Lloyd, Carter-Edwards, and Ellison also draw on community-based participatory research methods in their work with religious leaders in North Carolina. Their article demonstrates the need for increased partnership between university researchers and faith-based practitioners. To do this collaborative work, these authors argue that the university must position itself in a new light. It is advisable that the “university become a partner, community member, and co-learner, sharing both leader-ship and follower-ship. This emphasizes a shift away from an ‘expert’ model of delivering university knowledge to the public and towards a more collaborative model in which community partners play a significant role in creating and sharing knowledge to the mutual benefit of institutions and society.” Researchers and practitioners work together, sharing expertise, to improve community health.

As the authors here illustrate, the issue of directionality in research and practice in religion and health leads to a variety of complicated questions that must be explored. These include: How is health defined? How is health measured? Who determines what is worthy of interest or study? And what counts as “religion” or as a religious practice? This issue highlights the need for continued conversation around the aims and desired outcomes of research on religion and health and the directional agendas that shape this work and practice.

Religion Influences Health

Another theme that emerges among pieces in this issue is that of navigating the different worldviews aimed at the procurement of health and wholeness. For many of our authors, the impetus of their work is based on their personal experience of the vulnerable and fragile dimensions of bodily life. Nilima Abrams’ cinematic essay “Lotus” and Mazvita Machinga’s “Religion, Health, and Healing in the Traditional Shona Culture of Zimbabwe” both reflect upon family struggles with illness. They illustrate how meditation and African spiritual practices, respectively, assisted in the healing of family members. Abrams retrospectively notes the ways that a Buddhist practice of detachment and of engaging pain prevented her mother’s battle with breast cancer from becoming the overwhelming dimension of her family life. The title of the piece references Abrams’ own reflection that Zen Buddhist practice enabled her family to be calm and beautiful like a lotus flower in the midst of disease. Likewise, for Machinga, the Shona community understands her father’s mental illness as being treated both in terms of biomedical Western medicine as well as through religious healing practices. Shona rituals address an individual’s pain or suffering as they are manifested through troubled relationships between the individual and his or her ancestors and community. Thus, healing and wholeness involve the whole community and not only the individual’s biomedical care. For both Abrams and Machinga, it is not that biomedical paradigms take a back seat to non-allopathic health care; rather, communal and meditative practices combined with biomedical practices bring about healing in a more holistic way.

In addition to communal dimensions of illness, others write about how their own experience of illness is impacted by spiritual or religious practices and belief. In her essay “The Womb Circle: A Womanist Practice of Multi-Religious Belonging,” Monica Coleman explores her experiences of dealing with fibroid tumors in a collaborative healing group with other African American women. Drawing on African traditional religions, her experiences with this multi-faith group led Coleman to see that our “activities reveal our faith.” Rather than assuming that one might be situated in one discrete tradition or discourse while dealing with a biomedical condition, Coleman suggests that healing activities themselves reveal the multiplicity of our religious belonging. Arguing from a womanist perspective, Coleman contends that the binary of pluralism vs. exclusivist claims to truth is simply false in that it assumes that we live lives that are analytically commensurate. She suggests, rather, that our activities for health and wellness—no matter how dissonant or nonsensical (analytically speaking) they may appear—actually reveal how many people (including womanists) live lives in muli-religious belonging. Jamie Butcher’s piece “Theology and Disability: Providing Pastoral Care to the Aging” seeks to bring a disease to bear on reforming a particular theological tradition. Butcher, a pastoral chaplain at an elder care facility in Atlanta, GA, relates her own experience of celiac disease to the conditions of the elderly and disabled with whom she works. Rather than seeking to make sense of the vulnerable body in terms of a particular tradition (in her case, a Protestant outlook), she understands the activities of the body to be speaking back in order to modify a particular theological tradition. The life of the disabled, the sick, and the elderly can be a “spiritual opportunity” to modify the practices and outlook of a particular theological tradition. She interprets the language of “clay jars” in the Christian tradition as a reminder of the fragility of the human body. This shared point of weakness in the body functions as a means of reinterpreting the meaning of blessed life. For her, the practice of community building, of caring through vulnerability rather than in spite of it, may be a way to receive life as a gift and a blessing.

Health as Religion

The question of how health practices shape religious landscapes and identities was one that we were interested in pursuing in this issue and one that several of the authors highlighted here. For anthropologist Emma Varley, field experiences in a labor and delivery room in Pakistan led to her assertion that “religious identity and, more specifically, Islamic therapeutic resort arise within the domain of clinical service provision to alleviate risk, remedy harm, and attain well-being.” In the labor room, religious and medical authorities collide and align, and in this place (most often defined strictly in terms of allopathic medicine) we see the ways religious identity itself can be shaped through participation in the biomedical realm.

Sabine Henrichsen-Schrembs and Peter Versteeg assert, in their article “A Typology of Yoga Practitioners: Towards a Model of Involvement in Alternative Spirituality,” that the pursuit of wellbeing itself emerges as a religious practice for those affiliated with alternative spiritualities. They create a typology for understanding the motivation of yoga practitioners, which they then use as a “comparative tool for the categorization of people’s motivation to practice various forms of alternative spirituality.” As these authors illustrate, healing practices can shape religious identities that exist beyond traditional categories of religious believers and adherents. For some, seeking healing becomes itself a religious practice.

Several authors in this issue point toward experiential meeting points where it is difficult to discern where “religious” practices end and “healing” practices begin. The authors in this issue encourage us to be attuned to the ways that health practices shape religious identities and the ways that religious beliefs and practices can shape the experience of health and healing. This work calls attention to the need for increased interdisciplinary conversation about just what it is that those of us in the emerging field of religion and health set out to study, understand, and practice.

Conclusions

We would be remiss if we did not mention, with great sadness, the passing of one of Practical Matters’ advisory board members, Steve de Gruchy. De Gruchy’s work exemplified the intersections illustrated in this issue. His passion for engaging local communities to map and enhance the indigenous health assets they already possess marked a seminal moment in religion and health research and practice, as James Cochrane highlights in his memorial piece in this issue. Steve also contributed generously of his time to help us think through the key issues and audiences to be addressed in this journal issue. For his contributions to this journal, and for his work that lives on in his students and those he influenced, we are grateful.

We would also like to thank the faculty consultants for this issue, Thomas G. Long, Joyce Flueckiger, and Gary Laderman, for their unwavering support in the crafting of this issue. We would also like to extend our deepest gratitude to all the journal staff, our faculty advisor, Elizabeth Bounds, and the contributors who were so patient in bringing this issue to fruition. It is our hope that this issue of Practical Matters highlights the contexts and communities in which religion, health, and healing are connected and intertwined. As the authors presented here illustrate, this often happens in the context of ordinary life: a woman in labor, a man who seeks help with mental illness, or a community of differently abled people. We hope this issue sparks further conversation and reflection in each of these places, from Lesotho to Thailand to North Dakota to New York City.

Photo: Collage of bodymaps from a TICAH bodymapping workshop. Designed and produced by Jessica M. Smith and Jermaine M. McDonald.