Download PDF: Stephenson, I Have a Brick

Abstract

Church closure is a prominent phenomenon of the religious landscape in Europe and North America. Demographic and financial pressures, along with cultural changes, have led to the closure of scores of churches in recent years. Christian denominations are struggling to practically manage and pastorally and liturgically respond to church closure, deconsecration, and reuse of church buildings. This paper involves a study of the deconsecration of a small-town, rural church. The author argues that utopian theology and theory is ill-equipped to meet the challenges of deconsecration, since lived religious life, perhaps especially in small communities, is deeply rooted in a locative sense of and attachment to place.

Introduction: Mike’s Carpet Shop

We can imagine ritual sites as having life histories. After they are conceived, they grow and change; often, they die. Sadly, the latter is often the case due to lack of donations and contributions to the buildings of worship. Perhaps the building is converted for use by another tradition, or adapted to other uses. Parts may be recycled, or the site may be abandoned, left to rot and ruin; perhaps the site is demolished and cleared for new construction. Even when the transformation of places of worship seemingly moves in the direction from sacred to secular, there may be residues of the sacred, in the form of cemeteries or stories, or a change in how the sacred is understood.

Mike’s Carpet Shop, in Armley, West Yorkshire, England is one such place. Built as a Primitive Methodist chapel, in 1905, it is one of several churches in Armley that in recent decades has become something other than a church. The situation in Armley is not unique. In the past generation, and at a quickening pace, a combination of demographic shifts, cultural dynamics, and economic pressures has led to the closure of scores of churches across North America and Europe; we are going to be visiting one such church shortly, Highgate United Church, located in southwestern Ontario. Cases of church closure are widely reported in the news; photographers and filmmakers are beginning to explore the emotions occasioned by closure and demolition; public and private institutions of heritage and culture are launching preservation and conservancy projects to save threatened church buildings; and Christian denominations are struggling to practically manage and pastorally and liturgically respond to church closure, deconseration, and reuse.

Though sacred space is now an interdisciplinary subfield of study, church closure has received little attention.[1] In my current research, I am examining the phenomenon of church-closure at a number of sites chosen to illustrate the range of transformations taking place. The approach is to use ethnographic and visual methods, focusing on the ritual and performative events occasioned by church closure, collecting stories from congregations and community members, and working to better understand the issues involved in the reuse and transformation of sacred sites. My premise is that such occasions offer valuable insight into aspects of contemporary Christianity and the dynamic interactions between religion, culture, and the public sphere. The study of church closure raises a number of theoretical and theological ideas and issues focused not so much on matters of doctrine and belief as with questions of place and memory, respect and shame, success and failure. The reactions to and handling of church closure is a window on to the nature and meaning of “place” to practicing, contemporary Christians.

I stumbled across Mike’s Carpet shop many years ago, on the cover of Steve Bruce’s book God is Dead.[2] The cover, in combining a phrase from Nietzsche’s famous parable with the provocative image of Armley’s church/carpet shop, makes a claim: the fact that in western society we find many closed, abandoned churches is a sign that religion is in decline, if not altogether “dead.” The logic here is problematic; much depends on definition. If religion equals attending church and churches are closing then religion is, in some locales, in decline. In any case, I am not a secularization theorist, and my interest in the closure and transformation of churches is not sociological but ethnographic, and informed by the fields of ritual studies and the phenomenology of place. One shortcoming with Bruce’s cover image is methodological: after making its dramatic appearance, the actual place is never seen or heard from again. Bruce’s method is not informed by an interest in what David Hall, Robert Orsi and others have termed “lived religion.” Yet even a quick Google search of “Mike’s Carpet Shop” reveals that the building has had a very robust place in the lives and imaginations of local residents – showing up in poetry, serving as the model for birthday cakes, and a focus of civic debates over development, heritage, culture, and spirituality.

The line from the dramatic scene in Nietzsche’s The Gay Science that struck a chord with me when I first read it is not “God is dead,” but rather, “What after all are these churches now if they are not the tombs and sepulchers of God?”[3] A closed, abandoned, or transformed church is what Michel Foucault refers to as a “heterotopic” place. Heterotopias are places of otherness, deviation, and ambivalence; in-between, liminal sites, possessing layers of meaning and significance beyond their simple face value, as well as a quality of allurement evoked by their ambiguous, open status; Foucault explicitly names cemeteries as one example.[4] If we follow Bruce and Nietzsche in imagining a closed, abandoned church as a kind of tomb, we must nevertheless recognize that tombs and cemeteries are not secular, dead places, but the home of the dead; the locale of ancestors and spirits; repositories of cultural histories and memories; evocations of loss and longing. If Mike’s Carpet Shop is not a church, it is also not not a church.

The Closure of Highgate United Church

I want to focus on a particular place and event, the closure and deconsecration of a church in Southwestern Ontario, in the small town of Highgate, located in the county of Chatham-Kent. The case of Highgate is meant to shed light on the broader problems of church closure; in particular, I want to examine the interplay of ideas, theologies, and experiences of place.

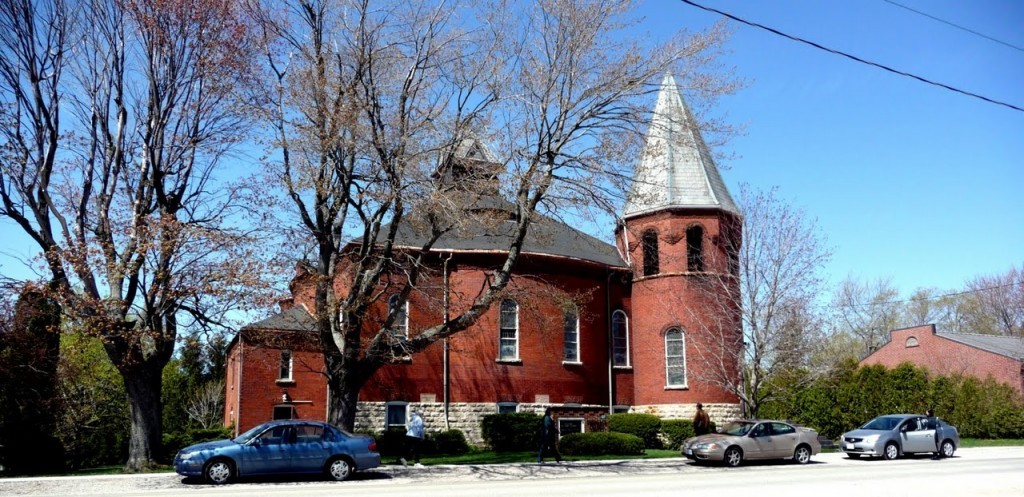

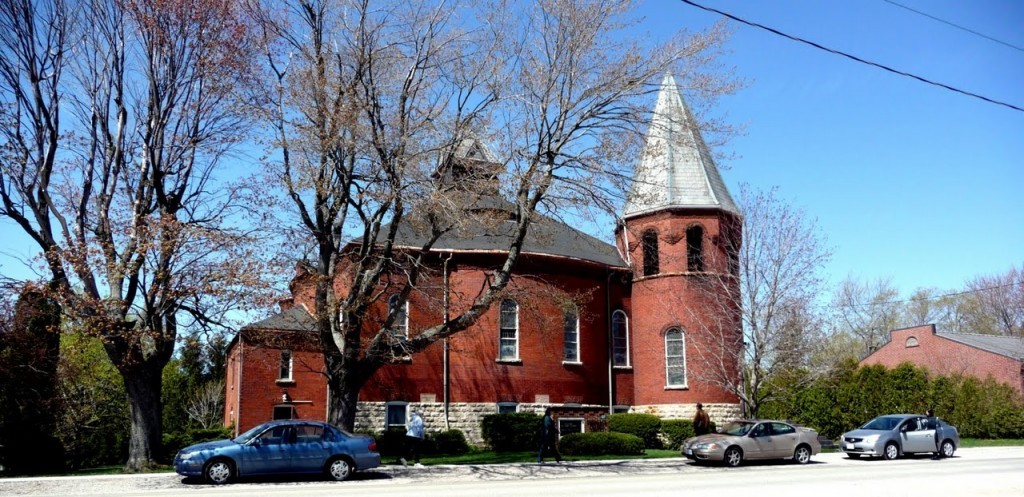

The Christian roots in Highgate extend back to the life of Mary Webb Gosnell, an Irish immigrant who established a Methodist congregation in her home in the early 1830s. Highgate’s United Church was originally built as a Methodist chapel in 1898, replacing a small timber frame church that had existed for a number of decades. Thirty Grand Master Masons led a procession for the laying of the cornerstone, and roughly 2000 people, an enormous number given the place and time, attended the ceremony. The church burned to the ground in 1917, but it was rebuilt the following year, according to the same plan. The Reverend T.T. George, who designed and oversaw the original building, returned to the town to see to it that the church was rebuilt; it seems George had something special invested in the building. In the 1920s, the church was folded into the United Church of Canada – a union of Methodist, Congregationalist and Presbyterian churches. For decades, the church served as a cornerstone of the community.

The building itself is architecturally unique; though the exterior walls are square, the building is overlaid with a circular structure, giving the church a rounded appearance. The circular design is complemented by a 75-foot high rounded bell tower entrance fronting the church; a square 16-foot lantern “dome,” set atop a rounded pyramidal base, caps the interior space. The Ontario Heritage Trust recently acknowledged the church as one a very few in North America built along such a unique design. The unusual design, along with a large pipe organ and excellent acoustics, made the church a standout in the landscape of small town, rural churches in the area.

Highgate’s is a rather common, small-town story. Fueled in part by the decline of tobacco farming in the region, over the course of a number of years the town lost its municipal building (to county amalgamation), its school, its gas station, its library, and much of its population. In March of 2009, the declining and aging congregation, reduced to worshipping in the basement to save on heating costs and no longer able to maintain the church, made the difficult decision to close. Working with my colleague, Ronald Grimes, four trips were made to Highgate over the summer months of 2010, visiting with congregation and community members, and tracking the various events that were being occasioned by the closure of the church. Taking the name of Mary Webb, a committee was formed, its members determined to save the church by transforming it into an arts and cultural center. (This transformation did occur, Highgate United Church becoming the Mary Webb Centre.[5]) The interest of Ontario Heritage led to a conference in the church on the “adaptive reuse” of church buildings. A photography exhibit and concert to promote the arts center was held. Lastly, on June 27, the deconsecration service, described as a “service of celebration and thanksgiving,” took place; it is this latter event that I want to examine.

The closure of the church generated excitement, energy, and anticipation associated with the possible transformation of the building into something new; but closure also meant a good deal of grief and uncertainty over impending loss. Two weeks before the church was deconsecrated, Ronald Grimes and I sat down with congregation members, after Sunday morning service, to listen and record their memories, stories, and concerns. Although I grew up on the other side of the country, Highgate is a culture and community that I know well: turkey dinners and angel food cake in the church basement, seeding and harvesting, pick-up trucks and baseball games, socially and politically conservative, salt-of-the-earth people, whose church was not merely a place of worship but served for decades as the orienting center of the community. Our conversation with the congregation was wide-ranging and, at times, emotional. Rural, elderly, United Church members are typically reserved; public displays of emotion are not common. On this occasion, however, those attending opened-up, spoke from the heart, laughed and cried with each other, in front of us, relative strangers, and on camera. It was a remarkable experience.

Below are two short clips from the four-hour conversation. First, you will see and hear Bonnie Fenton, a farm-wife who married into the community, but has been a long-time member of the Highgate congregation. Bonnie spoke eloquently about the pain involved in losing the church. The excerpt begins with her thoughts about the upcoming deconsecration service, and the pain involved in losing what she refers to as “our family church.” The second clip is of Mary Attridge, the congregation’s eldest member. Mary recalls the closure of another church, decades earlier, and the fact that she still has “a brick from that building.”

These clips were chosen because they emphasize a religiosity rooted in place, and a tension, even a disjunction, between this place-based religiosity and the pastoral and liturgical response to the closure of the church. This edition of Practical Matters focuses on the intersection of worship, ritual, and theory; my reflections here examine this intersection in the context of deconsecration, with the hope that there are some practical lessons to be learned or, at least, food for thought in thinking about and responding to deconsecration.

“Only a Building”

A phrase heard quite often during our research was “it is only just a building,” or “the church isn’t the building.” I want to explore this notion – “just a building” – teasing out its theological background and examining its consequences in the context of deconsecration. Moreover, there is a tension in this phrase that puts in question some common theoretical and conceptual notions we find in the field of religious studies. Lastly, I will reflect on the deconsecration service itself, in light of this “just a building” theme.

“People say it’s just a building…but it’s not just a building.” Who says it is just a building? Who are these “people” Bonnie Fenton references? There are, of course, (at least) two meanings to the word “church.” The church is the building in which Christians gather for worship. Scripturally and theologically, however, “church” has another meaning – the assembly itself – the assembly of the baptized, wherever they meet. It is this later meaning that has accrued greater weight and authority in Christian theology. And so, clergy and church officials, in talking about the upcoming deconsecration, readily reached for consoling but also rather reductive language: “remember, it [the physical church] is, after all, only a building.”

The implicit theology in such a distinction may be described as “utopian” (literally “no-place”), and it finds its way into the theorizing of scholars of religion. Jonathan Z Smith’s develops a distinction between utopian and locative strategies in mapping our relation to space, an idea that has held some sway in religious studies.[6] Locative traditions emphasize specific places in the landscape, orient towards a center, take an interest in ancestors, form identity in relation to local territory, customs, and stories. Utopian strategies, in contrast, seek to cut through the locative, emphasizing an abstract, idealized space: the Garden of Eden, Heaven, and Hell, unlike Tintern Abbey or the Washington Monument, are not so easily located. Scripturally and theologically, Christianity has had, from its beginnings, a strong utopian orientation, which is precisely Smith’s point. The New Testament represents a shift to a utopian view of our relations to place.

In the New Testament, we find but a few references to the holy city (Mt. 4:5, 27:53, Rev. 11:2), or the holy place (Mt 24:15; Acts 6:13), or the holy mount (2 Pet. 1:18); in general the use of the terms “holy” or “sacred” to describe or designate places decreases sharply compared with the Hebrew Bible. In the story of the Samaritan woman Jesus meets one of his few equals. They have a discussion that revolves around the water in a well (a well frequented, the woman informs him, by Jacob and other ancestors tending cattle) compared with the living water of eternal life. One of her pressing questions concerns the proper place of worship:

The woman said to him, “Sir, I see that you are a prophet. Our ancestors worshiped on this mountain, but you say that the place where people must worship is in Jerusalem.”

Jesus said to her, “Woman, believe me, the hour is coming when you will worship the Father neither on this mountain nor in Jerusalem… the hour is coming, and is now here, when the true worshipers will worship the Father in spirit and truth, for the Father seeks such as these to worship him. God is spirit, and those who worship him must worship in spirit and truth” (John 4:19-24).

Here, worship requires no place at all, but “spirit” and “truth.” In Matthew, Jesus travels with Peter and James and John (his brother) up a mountain, where he is transfigured, and meets Elijah and Moses. Peter, moved by the experience, suggest building three “booths” for worship, places for ritual activity – and he is rebuked. These examples (there are many others) illustrate that a locative sense of place is going out of fashion in early Christianity, replaced with a universalized, utopian orientation. People, we read, are the living stones of a new kind of temple, and the predictions of the destruction of Jerusalem function as prophetic critique of sacred space; any holy place marked for destruction has already been in effect desacralized. If useful for breaking down ethnic and other kinds of distinctions, or for a worldview focused on end times, utopian mapping nevertheless de-values local, rooted relatedness to place; moreover, a utopian orientation also prepares a ground for a highly exportable, perhaps even colonizing, religion: if Christianity requires no particular place, it can be in all places.[7]

It is precisely this kind of data that drives Smith’s comparative theorizing about different orientations to space. And so we have a received idea in our field that world religions tend to be utopian in character, while indigenous, small-scale religions are locative. But Smith’s categories do not work very well when we venture into the field to inquire about the religiosity of contemporary Christians, such as those living on farms and in small towns in southwestern Ontario. If Christianity is a utopian religion, is Bonnie Fenton’s United Church religiosity utopian? I hardly think so. There are levels of abstractions in religious studies; when we push down to the world of “lived religion” we often find our scholarly ideas challenged.

Bonnie Fenton’s religion is highly locative. The inspiring beauty of the dome evokes transcendence. Knowing her place in the pew is connected to knowing her place in the world. Baptisms, weddings, funerals-moments of passage in the course of a life-make the building not merely a container but a place, textured with emotions, stories, images, and feelings. As Lucy Lippard describes it, “place” is constituted by

the lure of the local…the geographical component to the psychological need to belong somewhere…that undertone to modern life that connects it to the past we know so little and the future we are aimlessly concocting…. Place is latitudinal and longitudinal within the map of a person’s life…a layered location replete with human histories and memories…It is about connections, what surrounds it, what formed it, what happened there, what will happen there.”[8]

Highgate’s church is “the latitude and longitude” of Bonnie Fenton’s life. In the tradition of phenomenology, space, abstract and uniform, is what we move through, while place is textured and has densities. Place is where we take pause, sit, and dwell. Space is a container (decentered, abstract, homogeneous, geometrical, universal, atemporal, neutral), while place is a medium (centered, concrete, unique, contextual, specific, temporal, powerful).[9] Place is to space as a home is to a house, or a community to a society.

Historically, traditionally, Christian theologies of place have tended to be utopian-Scripturally and theologically, Christianity is more temporally than spatially oriented, and little concerned with place-related needs. These “people” then who say that Highgate’s United Church is “just a building” are drawing on a scriptural, theological, and cultural tradition that devalues actual, physical, lived place in which the church, as a particular building, constituted by specific histories, memories, feelings, and experiences, becomes “just a building,” and not of ultimate significance or importance. Stated as a thesis, utopian religions and phenomenological place are at odds with each other; the mapping strategy that universalizes space is at odds with our place-related needs. The current preoccupation with place in both scholarly and popular literature reflects what a number of commentators refer to as a cultural crisis in Western societies-a sense of rootlessness, dislocation, or displacement; as Bob Dylan sings it, “Like rolling stone, with no direction home.” The loss of a church building that has served for so long as the orienting center of a community generates this experience of homelessness, and with it, emotional and spiritual pain and confusion.

The Deconsecration Service

Highgate United was deconsecrated in a Sunday “Closing Service of Celebration.” The church was brimming, as distant family members and former residents returned to the town for the occasion. Five of the church’s former pastors attended and participated in the service. The structure of worship was quite traditional: opening hymns, welcome and announcements, followed by an interweaving of hymns, bible readings, prayers and a sermon. The one unusual dimension of the service was the reading of a declaration of closure by a representative from the Presbytery.

We can imagine and categorize a deconsecration as a rite of passage. Certainly a deconsecration service marks a moment of transition and change. Barbara Myerhoff is among those ritual theorists who emphasize the role of passage rites in acknowledging and dealing with paradox and contradiction. We are individuals, yet also social beings; we live and we must die; we are the same person today that we were yesterday, and yet we change. Such paradoxes cannot be cognitively resolved; the best we can do, what we must do, Myerhoff suggests, is enact these tensions and paradoxes, honor them, respond to them, sit with them in song, dance, image, and gesture. For Myerhoff, good ritual is ritual willing to embrace paradox, rather than ignore it or deny it.[10]

The deconsecration of a church is such a paradox. The closure of Highgate United evoked both “only a building” and “far more than just a building.” Each of these responses seems (at least, to this observer) appropriate, fitting, and necessary. When I put on the hat of ritual critic,[11] I come to the conclusion that the deconsecration service failed to do justice to Bonnie Fenton’s “it’s not just a building” and Mary Attridge’s “I have a brick from that building.” The service did not embrace paradox but rather erased the deeply locative character of the congregation’s religiosity. This erasure was conditioned by a utopian theology of place.

The deconsecration service itself tended to deliver very utopian messages. Here is a short list, drawn from the words spoken during the service:

- “the loss of a building does not release us from our vows.”

- “religious life goes on regardless of the pew.”

- “don’t think of this as an ending.”

- “move on in your journey of faith; you are the church, regardless of the building.”

An opening hymn, “The church is wherever God’s people are praising,” written and used in the context of church dedication, emphasized the continuance of a “church” beyond the physical building. Similarly, the sermon drew heavily on Ezekiel, framing the closure in terms of exile and the visionary temple that can be carried wherever one sojourns.

Secondly, the church building primarily served as a container of the service; it was not thought of or used as a medium. Nothing was done to or with the building itself – no brick was removed and enshrined or washed or broken and scattered, or passed through the congregation. Time was not taken to contemplate at the dome or the stained glass. Stories of the building itself were not told. No one asked what the building might think or feel of the occasion. A more locative sense of religion would likely lead to a greater interaction with the specifics of the place of worship.

Lastly, the service had a very abrupt ending. The act of deconsecration was entirely verbal, the reading of a paragraph by an official from the Presbytery, announcing that the church was “no longer a place of meeting of the United Church of Canada.” These words were immediately followed by an awkward, “we have food,” from the pastor. The invitation to eat was undoubtedly meant to be comforting – but to my mind, it was representative of a broader reluctance to sit with the tensions and uneasiness that were palpably present. I wasn’t the only one who experienced this. Ray Fenton, Bonnie Fenton’s husband, interrupted the end of the service – there was more to say and do; he had some final thoughts and to his credit, he stood up, walked to the pulpit and spoke. His improvised addition to the end of the service was itself a kind of ritual criticism, rooted in a felt need to say or do something more. In short, Ray Fenton said, “We are ashamed that we haven’t been able to carry on.” I heard this sentiment of shame on other occasions, as some congregation members experienced the closure as a failure on their part, perhaps a moral echo of Proverbs (22.28), which cautions, “Do not remove the ancient landmarks which your fathers have set.” Ray Fenton ritualized this feeling by fitting it in, awkwardly, at the close of the service. He publically, formally acknowledged something that had to be said, difficult as it was.

Our relationship to abandonment, ruin, and decay is often aesthetic and hence distanced: for some reason, we tend to take a certain aesthetic pleasure in decay, ruin, loss, and abandonment. Such a contemplative stance avoids the question of agency, a question posed by Ray Fenton. Abandonment and ruin mark a larger event or narrative: the destruction of a group or community or society or civilization that erects the edifice, the expression of itself, only to, in time, see it fall into disrepair and disuse. Ray Fenton’s question is Nietzsche’s question, in that scene Steve Bruce alludes to: Who did this? Who turned the churches into tombs and sepulchres of God? Their answer is the same too: We did it.

Conclusion

The phenomenon of church closure is part of our contemporary religious landscape. There are many challenges in dealing with obsolete religious buildings; some of these challenges are conceptual, theological, and liturgical, areas that became apparent in documenting and reflecting on the closure of Highgate’s church. On the basis of my work at Highgate, I offer three cautions in thinking about and responding to deconsecration.

First, because Christianity tends to be utopian in relation to matters of place, the strongly locative nature of lived religion may be inadequately understood and addressed in the process of church closure. The conceptual, theological, and scriptural resources for interpreting church closure may result in a failure to adequately respond to the grounded experience of place held by members of a parish or congregation. We need to encourage, develop, and be aware of a locative sense of place.

Second, church buildings are not merely containers of worship services, but may themselves be actors. As John Seitz has discussed, in the context of parish closures in Boston, officials encouraged and hoped for an understanding of closed churches as empty vessels or shells; “it is not the building that ties Catholics together, but the valid and licit performance of the sacraments.”[12] A similar dynamic was apparent in the closure of Highgate; in both cases, this “empty vessel” approach was not adequate to the experience of some individuals, for whom the building itself was and remained sacred, if in an ambiguous fashion. In designing pastoral and liturgical responses to church closure, we need to think about integrating the building, its objects, and its memories into conversations and ritual action. Deconsecration services need not merely be held “in” the closing church; action can be centered “on” the church.

Lastly, we need to deeply acknowledge and make place for the experiences of loss, shame, sorrow, and disorientation that often accompanies church closure. Far too quickly, I think, a move was made to turn the Highgate deconsecration rite into a stage or a phase-a Kubler-Ross like moment-in the grieving and healing process. Ray Fenton brought the service back to what it was: the nadir, the lowest moment, a moment of symbolically identifying with deep failure, breakdown, death; in this sense Ray Fenton’s take on what was happening was perhaps more traditionally Christian than the service itself: What has happened here? We have failed. We are forsaken. One way of understanding tragic vision, including the crucifixion, perhaps, is that only by recognizing weakness, limitation, failure, can anything of lasting value be created. A service of deconsecration ought not occlude the sense of an ending, and the complex, tangled emotions that endings occasion.

Notes

[1] John C Setiz’s No Closure: Catholic Practice in Boston’s Parish Shutdown (Harvard, 2011) details the reaction in Boston to the announcement of parish closures, and raises a number of theological issues related to place, memory, and community.

[2] Steve Bruce, God is Dead: Secularization in the West (Wiley-Blackwell, 2002).

[3] Friedrich Nietzsche, The Gay Science, translated by Walter Kauffman (Vintage, 1974), p. 182.

[4] Michel Foucault, “Of Other Spaces: Utopias and Heterotopias,” translated by Jay Miskowiec, Architecture, Mouvement, Continuité 5 (1984): 46-49.

[5] Links to films made about the deconsecration – links removed for peer review.

[6] J.Z. Smith, Map is not the Territory: Studies in the History of Religions (University of Chicago Press, 1993).

[7] See Tod Swanson, “To Prepare a Place: Johannine Christianity and the Collapse of Ethnic Territory,” Journal of the American Academy of Religion 62.2 (1994): 241-63.

[8] Lucy Lippard, The Lure of the Local: Senses of Place in a Multicentered Society (New press, 1998), 7.

[9] Yi-Fu Tuan’s work introduced the distinction between space and place, the latter differentiated from the former by virtue of individuals and communities assigning or inscribing value and meaning to a locale. See his classic Space and Place: the perspective of experience (University of Minnesota, 1977).

[10] Barbara Myerhoff, “Rites of Passage: Process and Paradox,” in Victor Turner (ed.) Celebration: Studies in Festivity and Ritual (Smithsonian Institute Press, 1982), pp. 109-35.

[11] The practice of “ritual criticism” has been developed by Ronald Grimes, who approaches criticism as a variant or dimension of interpretation. Ritual criticism entails the “documentation and analysis of negative and positive evaluative claims”, as well as “interpreting a ritual with a view to implicating its practice.” See his The Craft of Ritual Studies (Oxford University Press, 2013), pp. 71-75.

[12] Seitz, 214.