Download PDF: Cho, Issue 11 Intro

Practical Matters is proud to publish Issue 11: Migrations and Religious Practices. Our hope was to bring together scholars and practitioners to critically reflect on the intersection of human migration, religion, and identity. As the collection of contributions demonstrates, this scholarly conversation has grown into something far richer than we anticipated.

Over the last few decades, a plethora of research on the intersections of religion and migration has been studied and published. From the beginning, sociologists and anthropologists have studied how migration shapes the religious beliefs and practices of individuals on the move. More recently, scholars of religious and theological studies have joined the conversation with particular attention to what both personal faith and religious communities mean for migrants as they cope with the various challenges of migration. Together, these numerous researchers have made it very clear that religion plays a significant role in the lives of migrants.

In 1978, Timothy Smith, in his seminal study on religion and ethnicity in North America, presented his groundbreaking argument that migration itself is a “theologizing experience.”[1] According to Smith, when migrants struggle with the disorienting experiences of loss, separation, and adjustment, faith provides its own language for them to make sense of their experiences, and also faith communities offer places of support and intimacy. Since the article’s publication, numerous empirical investigations have confirmed Smith’s “theologizing” view.[2] In many instances, religion accompanies the process of migration as a means of alleviating the traumas of departure and early settlement, provides a safe haven against external discrimination, and supports migrants’ smooth acculturation within in the new context.

Since the early 1990s, scholars have started considering the emerging question of how migrant individuals and communities establish and expand networks outside of their settlements through modern means of communication. This phenomenon is what has become known as transnationalism, “the processes through which immigrants forge and sustain multi-stranded relations that link together their countries of origin and settlement.”[3] With regard to religious life, many contemporary migrants build and maintain relationships with affiliated religious communities in their countries of origin as well as across the globe. Peggy Levitt claims the maintenance of global religious networks is possible because migrants engage in “transnational religious practices.”[4] Migrant individuals and communities participate in various religious practices, such as communion, pilgrimage, prayer vigil, transnational visitation, and long-distance consultation in order to “affirm their enduring ties to a particular sending-country group or place.”[5] In other words, global migration and transnational religious networks have also contributed to make a process of migration a “theologizing experience.” The enthusiasm for the theologizing view can be clearly seen even here in the pages of Practical Matters Issue 11: Migrations. In this issue, our contributors continue to expand and broaden this conversation by raising new questions about how historical and contemporary dynamics of migration profoundly shape global religious landscapes as well as the lived religious experiences.

Migration, Transnationalism, and Religious Practices

The first two articles open the issue by focusing on transnational religious networks and the religious leadership of women. Deanna Womack traces the history of the American Syria Mission’s tuberculosis hospital, the Hamlin Memorial Sanatorium in Mount Lebanon, from 1910-1930. Womack’s historical case study examines how this hospital opened a space for women to practice ministry and became a site of transnational and interreligious encounter. Nanette R. Spina also explores how women are privileged in positions of ritual authority and leadership in the contemporary context of a Canadian Hindu temple community, which is part of the transnational Adhiparasakthi organization, a South Indian guru-centered tradition. Based on ethnographic fieldwork, Spina highlights how its transnational setting creates a more gender inclusive space for Tamil migrants, especially the women, to exercise agency in constructing their religious identity by engaging in rituals and performances.

Christine J. Hong and Jaisy A. Joseph both aptly examine immigrant Christian congregations in the U.S., but with different directions. While Hong focuses on expanding the church’s sociocultural functions, Joseph critically reflects on theological ethnography as a method of studying immigrant congregations. By presenting the theological framework of a Korean cultural concept, Woori, Hong discusses how the Korean immigrant church has become a nurturing place of identity formation for second- and third-generation children and adolescents to navigate the complexities of bi-culturality, acculturative dissonance, and generational conflicts. On the other hand, based on her fieldwork with the Ethiopian migrants of the Ge’ez Catholic community in Boston, Joseph reimagines this particular congregation as “diaspora space” based on sociologist Avtar Brah’s work. Joseph convincingly argues how such space often puts a researcher in the experience of displacement, which contributes to a distinct pluralistic epistemology that is reflected both in the experience of migration and theological ethnography.

Moreover, Elina Vuola, Helena Kupari, and Andreas Kalkun’s contribution emphasizes the roles and meanings of religious practices in the process of migration. The three authors as a research team focus on the coping, healing, and commemorative aspects of Orthodox Christian processions and pilgrimages that are situated in symbolically significant landscapes in the historical home area of minority groups – Setos, (Border) Karelians, and Skolt Sámi in northern Scandinavia. This comprehensive qualitative study affirms the importance of religious practices that function as a coping mechanism for migrants as they struggle with loss and trauma.

Migration as an Alienating Experience?

But, is migration inherently and continuously a theologizing experience? What about those countless Syrian refugees in need of humanitarian assistance? What about those Mexican migrants who continue risking their lives to cross the U.S.-Mexico border? How do Muslim migrants in Europe make sense of the European nationalist movement that protests against their presence? By raising such critical questions, Patrick B. Reyes, HyeRan Kim-Cragg, and Cláudio Carvalhaes resist the dominant voice of the theologizing hypothesis and offer practical theological responses to the alienating experience of underprivileged migrants, notably refugees, asylum seekers, undocumented residents, and internally displaced persons (IDPs).[6]

Based on thoughtful reflection on the current political landscape in the United States, Reyes asks a compelling question: what practices, traditions, and resources do communities of faith have to respond to current immigration debates and policies? Drawing on his work with Latinx farmworkers and young adults of color, Reyes challenges us to know each other’s authentic story to explore how these narratives shape the shared sacred narrative of the community. Kim-Cragg also identifies migration as an urgent matter for practical theology by investigating vulnerability and resistance as the two conflicting sides of the migrant experience. Deeply rooted in the postcolonial reinterpretation of Canada as a contested space, her practical theological response calls for the harmonious pursuit of interdependence between the non-migrants and migrants in North America. Further, in his response to migration as global crisis, Carvalhaes boldly calls non-migrants to recognize all human beings as the carriers of the Imago Dei. He persuasively argues that the full understanding of the Imago Dei inspires faith communities to practice radical hospitality to the most vulnerable and alienating migrant individuals and communities across the globe. These three practical theologians bravely challenge the prevailing view on migration as a theologizing experience by being deeply committed to the voices of migrant individuals and communities directly affected by the authoritarian systems of border control and inhumane migration policies and management.

Expanding Conversations Beyond the Theme

Since its inception, Practical Matters journal has remained committed to publishing a wide range of outstanding scholarship pertinent to larger conversations in the field. The section Analyzing Matters features pieces that exceed the boundaries of the issue theme to touch on all matters of practical theology and religious practice.

Along with Joseph’s contribution, Lorraine Cuddeback-Gedeon broadens the conversation on theological ethnography. By identifying challenges in the case of doing fieldwork among people with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD), Cuddeback-Gedeon highlights the importance of the process of conscientization in doing ethnographic research by drawing on the work of Paulo Freire. The in-depth conversation on the philosophical insight of Freire continues in Christine Eunjoo Park’s contribution that proposes a new pedagogy of compassion. In this constructive practical theological task, Park places Freire in critical conversation with John Dewey, Henry A. Giroux, and Mary Elizabeth Moore as she traces and analyzes historical and contemporary understandings of compassion.

AnneMarie Mingo develops an ethics of receptivity that recognizes individual and institutional commitments to creating communities of mutual openness by evaluating displacement data and probing oral histories of the victims of Hurricane Katrina. On the other hand, Andrew Wymer constructs a new theological framework of “white bullshit” by drawing on a philosophy of bullshit, critical race theory, and the current political climate in the U.S. Building upon these theoretical foundations, Wymer examines the practical implications of white bullshit for homiletics. In these constructive works of practical theology, Mingo and Wymer both provide timely ethical and theological responses informed by the in-depth analysis of the sociocultural, political, and economic issues of the United States.

Conclusion

What’s truly significant is how most contributors in this particular issue have personal experience of migration, come from transnational spaces, and/or work in countries that have been often underrepresented in academic religious and theological discussion of migration. Their unique voices in these innovative methodological and theological explorations strongly affirm that the study of the intersections of migration and religion needs to be examined in ways that seek to acknowledge and disclose the complexity of the experience of migration.[7] Readers will find not every religious tradition, migrant group, or geographical region represented and discussed in the issue. But, our sincere hope is that these pieces may be used to generate more conversations in the classroom and faith communities, and also to inspire further research in the field.

I conclude with words of thanks for the exceptional work of the staff members of Practical Matters. The former Managing Editors, Matthew Pierce and Layla Karst shepherded this issue from its very beginning. The current Managing Editor, Lisa Portilla has created a productive space for the staff to engage in a fruitful conversation. Reviews Editor, Cara Curtis masterfully recruited and coordinated six remarkable book reviews. Furthermore, our newest members of the staff, Keith Menhinick and Palak Taneja, worked with such enthusiasm along with the rest of the Practical Matters staff to produce each of the pieces you will find here. Finally, I extend my gratitude to Dr. L. Edward Phillips who has served tirelessly as the coordinator of the Initiative in Religious Practices and Practical Theology and supported our journal for years with exceptional dedication.

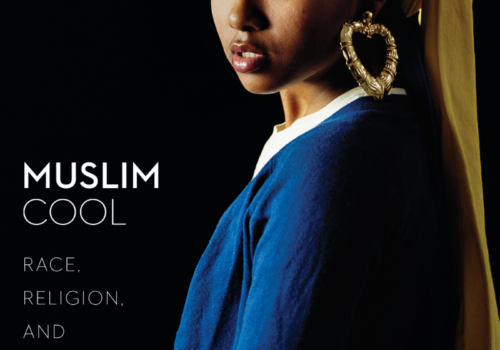

Feature photo by Creative Commons, CCO Public Domain.

Notes

[1] Timothy L. Smith, “Religion and Ethnicity in America,” The American Historical Review 83, no. 5 (December 1978): 1155-1185.

[2] For example, see Helen Rose Ebaugh and Janet Chafetz (eds.), Religion and the New Immigrants (Walnut Creek, CA: Altamira Press, 2000); Stephen R. Warner and Judith G. Wittner (eds.), Gatherings in the Diaspora: Religious Communities and the New Immigration (Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 1998).

[3] Linda Basch, Nina Glick-Schiller, and Christina Szanton Blanc, Nations Unbound: Transnational Projects, Postcolonial Predicaments and Deterritorialized Nation-States (Hoboken: Taylor and Francis, 2013), 8.

[4] Peggy Levitt, “Redefining the Boundaries of Belonging: The Institutional Character of Transnational Religious Life,” Sociology of Religion 65, no. 1 (2004): 2.

[5] Ibid., 5.

[6] For a sociological critique of Smith’s theologizing view, see James D. Bratt, “Religion and Ethnicity in America: A Critique of Timothy L. Smith,” Fides et Historia 12 (1980): 8-17.

[7] For more detailed overview of the theological exploration on religion and migration, see Martha Frederiks and Dorottya Nagy (eds.), Religion, Migration, and Identity: Methodological and Theological Exploration (Boston: Brill, 2016).