Download PDF: Buggs, Kaleidoscope Authorities

Abstract

In this essay I use the image of the kaleidoscope to reflect on the ways in which two African American laywomen, matriarchs in their families and religious communities, perform religious authority in the local church. Whereas discussions about women’s leadership in the church are often reduced to debates about ordination, these women represent those whose callings are as lay leaders, lay influencers, who play a vital role in the growth and sustainability of Black churches. I assert that the realm of religious authority is beautifully expanded by Black laywomen who claim their own authoritative voices. Their stories represent a constituency of women, Black laywomen who have given their lives and leadership to Black church communities and continue to do so. Regardless.[1]

Introduction

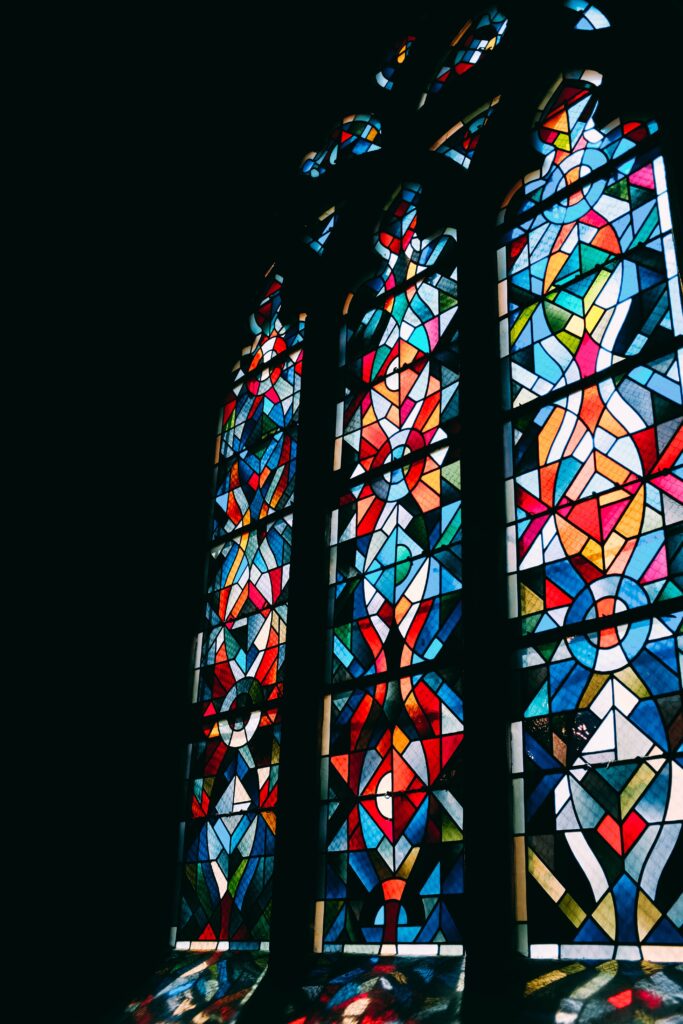

Colors and shapes – so many colors and shapes! That was my reaction to the do-it-yourself elementary school science project that consisted of making a kaleidoscope. The term kaleidoscope comes from a combination of Greek words meaning beautiful and shape or form. It is an instrument through which strikingly colorful patterns and shapes are made visible, depending on the angle of view. Even slight movements of the device and its interaction with light, reveal new patterns and shapes of colors, shades, and slight tints, interacting in ways that captivate my attention. As I reflect on being enamored by the kaleidoscope, it wasn’t just that I could see different images, but the images before me were differently beautiful and unique, yet integrally connected.

The varying images in the kaleidoscope come to mind as I explore what some may consider nontraditional notions of religious authority. When viewed from an axis of entry outside of the pulpit, religious authority takes on new shapes, new colors, new patterns. It is more egalitarian than hierarchal. It is more decentralized than centralized. It makes space for the beauty of mature Black women who might otherwise be deemed inconsequential to the formation and leadership of the church. With new light, religious authority is expanded to church mothers and women’s departments and the laywomen who may say very little yet have been anchors of Black churches for generations. These women have seen pastors come and go. They have seen visitors and members come and go. They have now worshiped in person and online. Through it all, they have led and do lead, in their own way.

In this essay I introduce two United Methodist Black laywomen—Cynthia and Arnetta (pseudonyms)—who were participants of a larger qualitative study on Black laywomen. Detailed descriptions of Cynthia and Arnetta enable readers to enter the worlds which inform their religiosity and shape their faith commitments. Specific attention is given to how the participants understand, interpret, and perform religious authority. Using countermemory and microhistories, I show how a re-reading of their religious histories through the categories of interpretive authority, institutional authority, and implicit authority reveals new ways of thinking about authority, particularly ways that decenter pulpit ministry.

Setting and Study Participants

Setting

The participants in this study are long-time members of the United Methodist Church. The congregation is predominately African American and spans a range of generations. At one time it was a family church, but in the past 20 years the church has increasingly welcomed newcomers to United Methodism and/or the local community. In its 150+ year history, the church has had two women pastors. Conversations with parishioners and listening to the sermons preached at this location reveal that the congregants lean politically Democrat and theologically conservative. There are more couples than single persons, and heterosexual marriage is regularly celebrated. There are also more baby boomers than millennials. The study site was selected because the congregation has a denominational history and local history that includes African American women functioning in leadership capacities at all levels. Additionally, I chose this study location because I had direct access to the congregation as an associate minister.

Insider-Outsider Risk Mitigation

My familiarity with persons in the congregation, particularly from pastoral care and Christian education perspectives, made this research vulnerable to bias and the unintentional influences of power. This is common in qualitative research that involves an insider-outsider positionality of the researcher. While I did not serve in a denominationally appointed leadership capacity, my role as a clergyperson in this particular religious setting carries an inherent degree of authority and power. I have preached at the location, led religious education studies, and performed pastoral care duties. Thus, there exists a familiarity with persons in the congregation, some more personally than others, and at the same time, I maintained personal distancing commiserate with what I consider appropriate and reasonable clerical boundaries, research aside. The lay-led culture of this congregation partly mitigates the power imbalance introduced by my clergy status. Additionally, my attendance as an associate minister from a different denomination makes clear to the congregation that I have no decision-making authority or judicial authority in the local congregation. The denominationally appointed senior pastor is the only clergyperson with formal authority. Still, the culture of this community is such that my identity and credentials as a clergy person carry expectations of spiritual leadership and, thus, a degree of deference to my clerical status.

To mitigate risks presented by the lay-clergy power differential, I took the following actions. At the onset of the research project, I explicitly identified the factors that could potentially impact this study at this location: familiarity, gender, personal background, and clerical status.[2] During participant recruitment, I intentionally selected interested persons with whom I had had limited contact or contact that did not involve discussions regarding my research interests. Having been at the location for four years, it was not possible to locate persons who knew nothing of my status as a researcher.

Prior to and during data collection, I reminded the participants of my role as a researcher, that their responses were confidential, and that they could speak candidly. The relationships I had cultivated as an insider seemed to minimize concerns about misrepresentation of the participants or their words. This was particularly important when participants shared comments that might be considered controversial or counter to the status quo. Participants were eager to share, often commenting, “No one has ever asked me about my experiences.” There seemed to be little to no concern about what I would or would not say or think; rather, I observed an appreciation for listening to their stories. I found that persons wanted to talk, wanted to be heard, wanted to tell of their journey. That said, as an outsider to the community of families within the church, and to the intricate relationships of the lay constituency, I acknowledge there were stories and histories to which I was not made privy.

While my positionality as a Black clergywoman is significant to the research, participants did not seem hesitant to name their pleasure and displeasure with lay and ordained leaders, regardless of gender. To some degree I attribute this to the ways in which they were familiar with my tendency to raised critical and not always popular questions during Bible studies. My precedent of welcoming departures from the traditional ways of reading texts created environments of honest interrogation. Therefore, the request for forthright responses in the research process was consistent with my previous practices.

Cynthia

Cynthia is an African American woman, born in the 1940s. She grew up on the West coast and after several relocations during her years of employment, she has settled in the South with her spouse. She is lighthearted, chatty, eager to share her story. At the onset of our interview she expresses how appreciative she is to participate. “No one ever asks about my story,” she interjects, “but I do have one.” She and her siblings were raised by a single mother, in a community of aunts and uncles and the Black Baptist church. Later in life she would align with the United Methodist Church. She laughingly shares how as a child the whole community watched her; any missteps in behavior would promptly be reported to her mother. As the daughter of a committed Christian, Cynthia grew up participating in various church activities. She had her first personal encounter with God during her school-aged years, an encounter that shaped her religious life for years to come. “At eight years old, God heard my prayer and opened the door for me,” Cynthia testifies tearfully, as she recounts a childhood story. Since then, she has believed in God as one who is able to do anything. She describes herself as deeply spiritual and a believer in miracles. When asked about cultivation of her spiritual life, she said prayer and “studying the Word” are key. A personal relationship with God is how she understands ministry. Living as a Christian is not about preaching; rather, it is about obedient living. She lives out her own authority through gifts of hospitality and caring for others and affirms the ways in which Black laywomen and clergywomen lead with care and compassion and expertise.

Arnetta

Arnetta is a lively African American woman of over 80 years of life. She is welcoming, and professional as we take our seats for the interview. She is a life-long United Methodist and has been in the same church for over 25 years. Unlike Cynthia, Arnetta shares few details about her upbringing beyond her Southern rootedness, but generously shares stories about her deceased spouse and adult sons. They are integral to her life in the church and commitments to community improvement. She shares pictures of her family, her church family, and other artifacts she has collected as the church historian. When her faith community was in the ‘old church’ they didn’t have storage space, so she kept programs and other memorabilia in suitcases, hopeful one day to share the contents with future generations. “I wanted us to remember our history, so I found a way to do it with suitcases.” Arnetta’s collection of seven large suitcases of materials would later be relocated to the newly formed church history and archives office. She has been an active laywoman with the United Methodist Women for as long as she can remember. Arnetta smiles as she talks about the many attributes of laywomen with whom she has worked over the years. The interview is filled with stories upon stories of laywomen leading in the local church.

Black Laywomen and Black Churches

“Whether in their roles as soloists, ushers, nurses, church mothers, Sunday school teachers, missionaries, pastor’s aides, deaconesses, stewardesses, or prayer warriors, women are at the core of the Black church, which could not exist without them. This reality is often eclipsed by the emphasis on the preaching and visionary tasks that define the pastoral office, which males have dominated.”[3]

Despite an overt orientation toward justice and equity for humanity, many Black churches in the 21st century still tend toward a narrow view of gender justice, even being referred to as “sites of sexual-gender oppression.”[4] Heterosexist, patriarchal norms remain prevalent though advocacy against other forms of oppression may figure prominently in stated ministry visions and mission statements. On the one hand, the Black church as an institution has been a cornerstone in the quest for social justice and equality, yet, on the other hand, has been less willing to examine internal gender injustice.[5] The injustice perpetuated against Black women in the context of Black churches is an ongoing subject of study and critique by both scholars and practitioners. That said, sexist practices have not left Black religious women impotent. In fact, Black laywomen in the 21st century continue a legacy of carving out their own spaces of religious authority with or without institutional validation.

Exclusively locating religious authority within the pulpit—a space to which Black women have limited access—erroneously obscures the agency employed by Black laywomen who perform religious authority beyond the boundaries of traditional clerical authority. Whereas critics may suggest that Black laywomen who participate in and support Black-male-dominated religious spaces perpetuate contemporary forms of patriarchy, this essay makes space for Black laywomen committed both to their traditional places of worship and to expanding what it means to perform religious authority, with or without external endorsement. The realm of possibilities for Black laywomen’s authoritative leadership is further expanded when sacred texts are interpreted in ways that include Black women. Stated differently, Black laywomen have not waited for a seat at the proverbial table; they have created new tables, in which their voices matter amidst other voices that matter.[6] The absence of access to or aspiration for the pulpit does not limit religious authority.[7]

In Righteous Content: Black Women’s Perspectives of Church and Faith, Daphne Wiggins shows how African American women in two Baptist congregations understand their religious commitments and relationship with the Black church. The monograph offers insights into the ways in which Black women were an integral part of the social uplift of African Americans as well as in building the religious institutions that sustained Black life in America at the turn of the 21st Century.[8] Wiggins particularly responds to the acclaimed Righteous Discontent, in which historian Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham provides an analysis of Black women in the Black Baptist church tradition from 1880-1920, and how they navigated class and race, while working to alleviate poverty and other ills that plagued Black communities.[9] Whereas Higginbotham portrays a view that women were unsettled about the denominational and churches affairs, Wiggins “finds evidence of a different resolve.”[10] Both authors capture histories of Black laywomen engaged in religious work, in the public and private sectors of life. The stories of Cynthia and Arnetta align with these stories in that they show evidence of a resolve to be active agents in the life of the church and community. The significance of this essay is how the participants reimagine what it means to have and execute religious authority in terms that empower themselves and others.

Methodology

This essay reports the findings of a larger qualitative study on perceptions of Black laywomen performing religious authority outside the pulpit. The study may be characterized as qualitative narrative inquiry in that it “studies the lives of individuals and asks one or more individuals to provide stories about their lives.”[11] Narrative inquiry typically elicits a sequence of ordered events connected in a meaningful way for a particular audience.[12] Drawing from the traditions of literary theory, narrative inquiry assumes that “people construct their realities through narrating their stories.”[13] Narrative inquiry has a long history in the humanities because of its focus on the voice of participants, and how those voices are shaped by a myriad of factors.

Data collection was via interviews and two focus groups. The interview questions were semi-structured, allowing the participant to elaborate on or deviate from the questions with personal anecdotes, at will.[14] The purpose of the individual interviews was to allow participants to respond to the research questions at length, narrating stories of the role of African American women performing religious authority.

Focus groups were used in this study to gather data about how participants’ perceptions about African American women in religious spaces took shape in communities, both religious and non-religious. Religious communities are spaces in which persons make sense of the world. Participants shared about how their understanding of faith and religious practice took shape in the context of their social worlds. The group setting was also intended to mitigate resistance to solo interviews.[15]

Participant Selection

Study participants were required to meet two criteria: over 18 years of age and active membership in the congregation for a minimum of six months. The study was intentionally geared towards adults who may have experienced women in religious leadership in this context or other contexts, and formed opinions about said leadership, however malleable those viewpoints may be. Active participation at the study site means persons were reasonably present for six months, which would in turn result in some degree of exposure to African American women performing religious authority. Regular presence at the study site also indicated connection and communal ties to the location by suggesting participants have a vested interest in the activities of this specific congregational assembly.

For this essay I selected two of the ten original participants, Cynthia and Arnetta: two Black laywomen over 65 years of age. If Black women are overlooked in contemporary society, all the more are Black women in their winter years. This is an understudied community and I contend that their histories convey a glimpse of what it means to do the work of sustaining Black communities and Black religious life, without expectation of or desire for formal recognition. Their interests are not (and have never been), in ordained ministry; they are interested in effective leadership for growth of the local church. Their stories reveal how understandings of authority are influenced by culture, familial upbringing, and engagement with scripture. Such histories move discussions about religious authority and agency in Black women’s religious lives beyond the oft touted women’s ordination disputes. “To equate the official ordination of female clergy with female power,” writes Wiggins, “obfuscates other manifestations of women’s power and agency.”[16] Furthermore, it renders insignificant the ways in which Black laywomen create alternative power bases in the community and in the church. This alternative agency is not without merit.

Even as local church memberships decline for some demographics, Cynthia and Arnetta represent those aged women who have committed themselves to ‘stay in the ship’, that is, the fellowship of their local Black church. Longevity gives them a view across time that helps make sense of contemporary time. Their religious authority takes various forms, yet it is undeniable.

Counternarratives

Building upon the heritage of African foremothers who were “priestesses, queens, midwives, diviners, herbalists…female deities…and rulers,”[17] contemporary Black laywomen claim and execute religious authority. The largely male leadership of mainline Black denominations and other faith traditions might suggest a docile following of women, but Black churches would scarcely survive without the active support of Black women.[18] The religious lives of Black women cannot be reduced to simplistic arguments over women’s ordination; rather, they reflect a breadth of religious activity that expands notions of religious authority. This essay uses countermemory and microhistories of Cynthia and Arnetta to blur, even cross, the traditional boundaries of religious authority.

In Womanist Ethics and the Cultural Production of Evil, Emilie Townes deconstructs the myths of Black women as Mammy, Sapphire, Black Matriarch and Topsy, and contends that these images are mythical portrayals of Black women that serve to reinforce white hegemony, patriarchy, and dominance in discourse. Utilizing the interplay of memory and history, Townes shows “how a stereotype is shaped into truth in memory and in history.”[19] Counternarratives disrupt the denigrating ‘truths’ perpetuated about Black enslaved women and free women under the gaze of racism. For instance, the mythical Mammy is unraveled as an image produced by the white psyche to refute accusations that white slave owners raped Black enslaved women. “Mammy is constructed as an ugly antidote to such charges,” Townes writes. “After all, who would abuse a desexualized, fat, old Black woman when the only other morally viable alternative was the idealized white woman?”[20] The Mammy image “confuses and distracts from the living proof of miscegenation.”[21]

At the core of Townes’ project is her ethical commitment to humankind, in general, and Black women and women of color, in particular. Townes envisions the use of microhistories and countermemory as means to dismantle evil productions of Black women. Echoing George Lipsitz, Townes writes, “Countermemory is that which seeks to disrupt ignorance and invisibility. It is a way of “remembering and forgetting that starts with the local, the immediate, and the personal.””[22] Countermemory is a reconstitution of history.[23] The local histories of Black women, told by Black women, are “microhistories…ignored or forgotten or discounted histories of real people….”[24] Microhistories allow history to be told another way. Careful consideration of the microhistories of Cynthia and Arnetta enable readers to reject portrayals of Black laywomen as voiceless women responding to the demands of religious institutions and Black male clergy. By hearing their stories in their terms, their commitments to the uplifting of Black churches as thoughtful execution of religious authority, rather than compulsory service, are made visible.

In the following paragraphs, I use the categories of interpretive authority, institutional authority, and implicit authority to show how Cynthia and Arnetta perform religious authority. It is at the intersection of these authorities that contemporary Black laywomen faithfully live out the contours of authoritative religious life.

Interpretive Authority

“I think now we all have religious authority. If you are a believer in Jesus Christ, and live according to his word, then He has already authorized us to spread the Good News. So, of course we adhere to the hierarchy of organized religion, wherever we may be, but we [lay members] have religious authority also.”

– Cynthia

Traditional textual interpretations about the place of women in the church are upended as Black laywomen claim the right to interpret scripture from perspectives that affirm their humanity, without permission asked or granted. Choosing to exercise religious authority based on one’s relationship with the Divine as interpreted from sacred texts is a performance of ontological assuredness that does not seek external endorsement. It is the ‘I know that I know that I know’ stance that challenges what seems most pragmatic and prudent and normative. Choosing to claim authority for oneself is at once resistance against Empire and acceptance of Imago Dei. It is rejection of power that denigrates Black women—be it in religious or nonreligious spaces—and reception of Black women as constituted of the Divine.

Interpretive authority is informed by how one views the salvific relationship, or what Arnetta refers to as the exchange. The Divine-human encounter is grounded in the exchange of giving and receiving, which begins with seeing. God sees the needy condition of humankind and gives, as One who is capable of giving. Humankind, in turn, is to see the needs of the world and give hope and help. This process of exchange is an ongoing series of exerting and accepting of authority, by all believers.

When questioned further about the nature of religious authority, Arnetta is thoughtful and reflective. She understands religious authority in the context of three terms: giver, receiver, and influence. She explains how in relationships there exists an ongoing shifting of positionality, between givers and receivers, and religious authority is performed in the influence one has from both positions. “It is not just what you do as the leader or the giver,” explains Arnetta, “it is also how you receive from others and allow them to demonstrate their authority.”

Arnetta emphasizes that spiritual authority resides with all Christian believers. For example, Matthew 28:20 is interpreted as a call and command to all. Arnetta interprets sacred texts in ways that include her own authoritative voice. Authority that comes directly from the Divine is not limited to positions or certain persons within the faith community; it is for all who believe and are willing to accept it. These convictions are based on interpreting sacred texts in ways that empower all believers, irrespective of clerical office or lack thereof.

Moreover, Arnetta expresses understanding religious authority as a spiritual responsibility to and for others. She says that Black women have a way of seeing needs and are particularly equipped to meet the needs they see. The needs of humankind are always great, and Black women, laywomen, are uniquely positioned to meet those needs. In this interpretation, religious authority is used in the service of others, rather than in exerting power over others. It is shared authority among persons of faith, for the building of community and betterment of the world.

“Years ago, I was chairperson of council on ministries in my church and I worked very well with it. But there were times when I not only had to present…I had to get them to see it. And I could feel that I as I was giving to them, they were giving to me too, religious authority was involved in that.”

– Arnetta

This is not to suggest that Black women ‘meet the needs of the world’ to their own demise or self-sacrifice. Interpretive authority involves seeing oneself first in the text and in the image of God; then seeing others and engaging others with the eyes of God. Cynthia’s interpretive lens was not so inclusive.

Cynthia expressed that though she is now supportive of Black women’s authority, this has not always been the case. She recalls her disapproval of Black women who pursued ordained ministry and resistance to their preaching. “The man was the pastor,” she stated definitively. The tradition of “men are the head” as a reinterpretation of Paul the Apostle’s teachings contributed to Cynthia’s rejection of the authority of women in religious spaces, especially Black women. Her adherence to “women should be silent” caused her to rebuff women who chose to speak or teach, not to mention those who dared to preach in the church. She recalls her suspicion and outright refusal to listen to Black women who claimed to have a ministerial call. Cynthia confesses how her mother taught her to question the intentions of other women, leading her to distrust Black women. Some Black women have been taught to treat one another as suspect, always in competition with one another, rarely complimenting one another. Consequently “horizontal hostility” emerges as a separator or limiting condition.[25] Not only may Black women distrust their own internal power, but also, they may distrust one another.

In her later years Cynthia has abandoned such thinking and fully supports Black women in all ministry capacities. She attributes her shift not to theological growth or expanded scriptural interpretations, but to life experiences and personal engagement with Black clergywomen. In contrast to what she had been told about Black women’s leadership, Cynthia’s experiences of Black clergywomen are positive, inspiring, and enriching. Her understanding of religious authority is now broad enough to include every Christian believer – even Black laywomen. Cynthia doesn’t try to interpret or explain texts that are used against women in ministry; in this case, she allows her lived experiences to inform her theological convictions.

Institutional Authority

Institutional authority is that which is given by governing entities, through the process of ordination or licensing. Cynthia and Arnetta acknowledge that there is a validation process involved in granting religious authority for the leadership of their local church. While it is the responsibility and right of all believers to participate in the life of the church through service, there are those who are singled out to lead congregations in more formal appointments.

“Religious authority can mean an individual that has been ordained or has been voted, nominated by the church members to lead. Again, I think that one has to recognize the Spirit of God that is within them to move forward into that position.”

– Cynthia

Formal callings to religious leadership may be supported scripturally; for instance, see Ephesians 4. Institutional authority is tangential to interpretive authority, in that it is grounded in scripture, yet differentiates a level of authority that extends beyond that of every believer. Cynthia emphasized the process of receiving institutional authority within the United Methodist Church as an ordered structured process.

“In my experience, there was always some steps they had to go through. And that authority was given through someone who maybe had a step up, could have been a pastor at a church who might have nourished someone’s growth…”

Both participants mentioned persons in the congregation who’d acknowledged a call to formal ministry and engaged in the ordination process. Clergypersons having received religious credentials from other authoritative bodies were also active in the congregation.

Institutional authority for lay persons functions differently. Church culture is a key element in how women navigate religious spaces. Arnetta describes a culture in which the authority of laywomen was accepted and expected. She has always supported Black laywomen and clergywomen. “They have a little something extra,” says Arnetta. “I don’t want to call it enthusiasm,” she says with a chuckle,” but it is a different kind of energy in the church…something that is noticeable…or more recognizable.” She is hesitant to articulate gender preferences but admits that she has seen what capable Black women do and it is always inspiring. Arnetta bears witness to an internal lifeforce,[26] an undeniable energy, as normal to her experience of Black women in leadership. She doesn’t recall a time when she questioned the significance of Black laywomen’s guidance to the church: “We’ve always been here and we’ve always did what needs to be done, with or without the men.” Even without formal religious authority, laywomen are ‘endorsed’ by the congregation because of their character, capacity, and tenacity for ministry.

Conversely, when asked about religious authority, Cynthia responds with memories of the preachers at her church—all Black male preachers—and the ridicule women experienced if they even hinted at a call to preaching ministry. As indicated above, in her formative years she understood pastoral ministry in the context of “God calls men. The man is the head.” She was not a proponent of women leading in the church context without male oversight and held deep convictions that women should follow male leadership because “God chose them.” In her teen years she began to question her carte blanche affirmation of male leadership as she witnessed behaviors that were inconsistent with what she considered as Christian behavior; however, still, she admittedly, and now ashamedly, preferred male leadership. It would be well into her adult years—the 1980s—before she would question patriarchy and the dearth of women in ordained ministry.

The prevalence of active lay and clergywomen in the United Methodist Church significantly impacted Cynthia’s shift toward acceptance of women’s leadership. She concludes with a pride-filled smile, “I am now thankful that my church has a lot of women in the pulpit; may it encourage others to step forward and let the Lord use them. I like to see women lead.” It is worth noting that rejection of Black women in ministry by Black laywomen is not uncommon, particularly for women of Cynthia’s generation, and this horizontal hostility continues as a negative spoken and unspoken undercurrent. Nevertheless, Black women, called by the Divine, persist.

Implicit Authority

I refer to implicit religious authority as that authority granted to individuals from the community based on observed initiative, the propensity to lead, and capacity for effective leadership. Stated another way, implicit religious authority is evident when persons follow or adhere to the guidance of those who do not initially function in established leadership positions. The authority of Black laywomen most closely identifies as implicit authority in that it emerges within or is derived from their willingness to do the work of ministry. For example, Cynthia observed her mother and aunts always involved in church activities, even if they didn’t lead the activities. Over time, they were invited to committees, subcommittees, and other positions in which they exerted varying degrees of influence. Even if they resist formal leadership appointments, they are not excluded from the informal authority granted by participant observers. This type of organic leadership is often rooted in character, personality, ethics, and demonstrated commitment to the life of the church and a life of ministry.

Cynthia’s early resistance to women clergy is not to suggest that women in her religious upbringing did not lead. In fact, Cynthia’s mother led subcommittees and participated on various boards in the church. Her mother didn’t talk about leading, she just led. In reflection, Cynthia reevaluates the activities of her mother, and aunts, and other Black laywomen as “just as necessary as preaching, and at times more important for the maintenance of the local church.” She acknowledges the irony of the gifted Black laywomen who were informal leaders yet resisted the ministerial leadership of Black women ministers. Her view of women’s authority in the church drastically changed as she experienced first-hand Black women’s leadership. Whereas her conservative Baptist upbringing caused suspicion of the progressive ideas of white feminists, she found an affinity with other Black church women who led with character, integrity, and self-advocacy. Their commitment to the church and the community, in the face of sexist practices, transformed Cynthia’s thinking. She now finds herself leading and mentoring younger women to assert themselves in every aspect of their lives.

The ability to recognize needs, organize a plan, mobilize people, work with others, and inspire participation are characteristics Arnetta describes of those performing religious authority. Often these traits are observable yet not properly recognized as vital for effective informal leadership. Additionally, she notes how there is a degree of authority that comes by one’s willingness to serve. Arnetta proudly offers an example: the ‘Improvement Committee.’

“This group of laywomen assembled themselves to help with fundraising for new musical instruments and organizing to welcome new families. They organized, strategized, and executed their plan. In the end, they raised more money than needed, and the excess monies became the seed investment for a new church building.”

Arnetta tells this story as an example of the ways that Black laywomen perform religious authority. While she acknowledges Black male leadership, it is inconsequential to our conversation. Arnetta’s focus is on the ingenuity and agency of Black laywomen, and their ability to “get things done on their own.” By her estimation, laywomen are critical to the church. They are more than capable.

The willingness to serve without compulsion surfaced as an undertone of implicit authority. Participants repeatedly stated that one must want to lead and serve for religious authority to be realized. Additionally, they affirmed that the authoritative posture of Black laywomen is in both their being and their doing. Specifically, Cynthia and Arnetta described the performance of religious authority as what they do and who they are. In womanist fashion, they both name themselves and engage in communities that call forth better versions of self than would be realized in isolation from the community. They claim their own identity and capacity to be their fullest selves. Little attention is given to how others interpret their generous service; they interpret it for themselves. At the same time, Cynthia and Arnetta affirm the value of other voices—communal voices—that are instrumental to their development.

Conclusion

Cynthia and Arnetta enable us to see beyond the myth of pulpit power as singular power in Black churches. Laypersons, Black laywomen, are the life force, yes, the dynamo, of Black churches. Though our discussions about religious authority were not intended to point to clergywomen (or those in ordained ministry), the prevalence of commentary about Black clergywomen suggests a subconscious privileging of institutional authority. Moreover, persons serving in ordained ministry capacities other than pastorates, for instance, chaplains, were secondary considerations when describing the practice of religious authority. As Cynthia and Arnetta moved beyond their preliminary responses, they expressed practices of religious authority that include everyday religious practitioners. Still, the initial responses may indicate an unconscious expectation about religious leadership and external validation, and possibly about gender. More specifically, the responses indicate that while Black laywomen of their age group acknowledge their own authority, they also value institutional validation by governing bodies such as denominational authorities and/or institutions of higher learning.

This observation is significant because Black women have historically been excluded from the highest levels of Black local church leadership, whether by denominational policies, lack of validation by the local religious body or leaders, or some combination of the two. While some congregations may affirm Black women’s pastoral leadership, the pipeline to that leadership lags due to pulpit gatekeeping, even as Black women who meet all formal (and informal) requirements continue to emerge. For example, when Black women are redirected from pastoral leadership opportunities to administrative support positions, religious bodies impose a camouflaged form of marginalization. This redirection, in effect, reinstitutes Black male-dominated church leadership, despite inclusive rhetoric that suggests otherwise. The selection of Black women as Executive or Assistant Pastors rather than Senior Pastors is a case in point.

Nonetheless, the microhistories of Cynthia and Arnetta—told in their words—allow us to witness a different resolve. We witness a story of change and growth, liberation and transformation, advocacy and affirmation. Cynthia shows us the value of personal experience and how one may evolve emotionally, cognitively, and theologically. Her complex journey to acceptance of Black religious women as leaders is not uncommon. In contrast, Arnetta trusts herself to think theologically and analyze texts in ways that are liberative to her own being and others. She embraces Black women as leaders in the same way that she embraces her own capacity to lead. They both hold their own truths, against academic theories that may portray them in ways that conflict with their self-perceptions. Stated differently, they name themselves as they see themselves. While they would not call themselves womanists, they embody what womanists refer to as radical subjectivity and traditional communalism.[27] They navigate the church and the world with an authoritative presence that matters because they say it does, not because someone told them so. A kaleidoscope view enables us to see the beauty and richness of their contributions to Black church life and leadership.

Finally, their commitments to the local church—in person or virtually—suggest a value system that may be contested in the digital age of worship. The prevalence of virtual worship experiences in recent years has raised questions about what it means to commit to a singular faith community as opposed to a commitment to practice one’s faith, in whatever ways and spaces one chooses. Cynthia and Arnetta represent a cadre of churchgoers who retain a sense of loyalty to the institutions they helped build. It is not because they have to; it is because they choose to. Further writing on this topic may include interrogation of what constitutes stick-to-itiveness to religious institutions, when worship sampling is normal in digital space. What enduring lessons might contemporary worshipers glean from worshipers in their winter years, like Cynthia and Arnetta? Moreover, how might congregations move forward with the Cynthias and Arnettas who labored and do labor, opting not to leave them behind?

Feature image by Adrien Olichon on Unsplash.

Notes

[1] Alice Walker, In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens: Womanist Prose, A Harvest Book (Orlando: Harcourt, 2004). The use of this term in this way is consistent with its use in womanist discourse. It is a way of saying that no matter what and against any odds, Black women do as they must and be who they are.

[2] John W. Creswell, Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 4th ed (Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, 2014), 237.

[3] Daphne C. Wiggins, Righteous Content: Black Women’s Perspectives of Church and Faith (New York: New York University Press, 2005), 2.

[4] Marcia Riggs, Plenty Good Room: Women Versus Male Power in the Black Church (Cleveland: Pilgrim Press, 2003) 65. For Riggs, the term ‘site’ signifies the examination of the Black church as “a particular context that shapes the encounters between African American men and women into practices that promote the subordination of women by men.”

[5] Riggs, 80.

[6] This essay builds on the scholarship of Cheryl Townsend Gilkes, Evelyn Higginbotham, Daphne C. Wiggins, and Estrelda Y. Alexander by addressing the ways in which Black laywomen have helped shape Black churches and communities by their leadership and support of others who lead.

[7] In this case, the pulpit refers to pastoral leadership or those functioning in ordained ministry.

[8] Wiggins, 10.

[9] Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham, Righteous Discontent: The Women’s Movement in the Black Baptist Church, 1880 – 1920, 7. print (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2003).

[10] Wiggins, Righteous Content, 11.

[11] John W. Creswell, Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 4th ed (Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, 2014).

[12] David Silverman, ed., Qualitative Research: Issues of Theory, Method, and Practice, 3rd ed (Los Angeles: Sage, 2011).

[13] Catherine Marshall and Gretchen B. Rossman, Designing Qualitative Research, 5th ed (Los Angeles: Sage, 2011).

[14] Flick, Introducing Research Methodology, 112.

[15] Yin, Qualitative Research from Start to Finish, 142.

[16] Wiggins, Righteous Content, 113.

[17] C. Eric Lincoln and Lawrence H. Mamiya, The Black Church in the African-American Experience (Durham: Duke University Press, 1990), 276.

[18] Lincoln and Mamiya, 275.

[19] Emilie Maureen Townes, Womanist Ethics and the Cultural Production of Evil, (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006), 3.

[20] Townes, 31.

[21] Townes, 32.

[22] Townes, 22.

[23] Townes, 24.

[24] Townes, 15.

[25] Audre Lorde, Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches (Berkeley, Calif: Crossing Press, c2007, n.d.), 48.

[26] Lorde, Sister Outsider. Lorde uses the language of life force to describe the erotic essence inherent to women.

[27] Stacey M. Floyd-Thomas, ed., Deeper Shades of Purple: Womanism in Religion and Society, Religion, Race, and Ethnicity (New York: New York University Press, 2006).